The Warlord of the Air (18 page)

Read The Warlord of the Air Online

Authors: Michael Moorcock

M

y first thought was that I had been lifted out of the frying pan into the fire. But then I realized that it was the habit of many Chinese warlords to hold their European prisoners to ransom. With luck, my government might pay for my release. I smiled to myself when I thought that Korzeniowski and Company had innocently taken on board a gang of rascals even more villainous than themselves. Here was the best irony of them all.

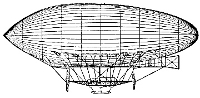

General O.T. Shaw (or Shuo Ho Ti as he styled himself for the sake of his Chinese followers) had built himself an army of bandits, renegades and deserters so big that it controlled large areas of the provinces of Chihli, Shantung and Kiangsu, giving Shaw a stranglehold on the routes between Peking and Shanghai. He charged such an extortionate sum as a ‘toll’ on trains and motors which came through his territory that trade and communications between the two cities were now conducted almost wholly by airship—and not every airship was safe if it flew low enough to be shot at by Shaw’s cannon. The Central Government was powerless against him and too fearful of seeking assistance from the foreigners who administered large parts of China which were not in the Republic. For the foreigners—Russians and Japanese for the most part—might make it their excuse to occupy that territory and refuse to leave. This was what gave Shaw—and warlords like him—his power.

I had been taken aback at meeting such a famous and romantic figure in the flesh. But now I managed to speak.

“Why—why should you want me to fly the ship?”

The tall Eurasian smoothed his straight, black hair and looked more like a devil than ever as he replied softly: “I’m afraid Mr. Barry is dead. Captain Korzeniowski is wounded. You are the only person qualified to do the job.”

“Barry dead?” I should have been exultant, but instead I felt a sense of loss.

“My men reacted hastily when they saw he had a gun. They are frightened, you see, of being so high in the air. They feel that if they die the spirits of the upper regions—devils all—will capture their souls. They are ignorant, superstitious men, my followers.”

“And how badly is Captain Korzeniowski hurt?”

“A head wound. Not a serious one. But, naturally, he is very dizzy and not up to commanding the ship.”

“His daughter—and Count von Bek?”

“They are locked in their cabin, with the captain.”

“Steeton?”

“He was last seen on the outer catwalk. I believe he fell overboard during a fight with some of my men.”

“My God,” I muttered. “My God.” I felt sick. “This is piracy. Murder. I can hardly believe it.”

“It is all of those things, I regret to say,” said Shaw. I recognized the soft voice now, of course. I had heard it earlier when they had been arguing in the opposite cabin. “But we do not wish to kill any more, now that we have control of the ship and can fly it to Shantung. None of this would have happened if your Count von Bek had not insisted we go to Brunei, even though I warned him that the British were aware he was aboard

The Rover

and would be waiting for him there.”

“How did you know that?”

“It is the duty of a leader to know everything he can and so benefit his people accordingly,” was the rather ambiguous reply.

“And what will you do for me if I agree to help you?” I asked.

“It is what we shall do to the others which might interest you more. We shall refrain from torturing them to death. This might not impress you, however, since they are enemies of yours. But they

are

—” he lifted his right eyebrow sardonically—“fellow white men.”

“Whatever they are—and I’ve nothing but contempt for them—I wouldn’t want them tortured by your ruffians.”

“If all goes well, nobody will be harmed.” Shaw uncocked his revolver and lowered it, but he did not put it back in the holster at his hip. “I assure you that I do not enjoy killing and I give you my word that the lives of all aboard

The Rover

will be spared

—if

we reach the Valley of the Morning safely.”

“Where is this valley?”

“In Shantung. It is my headquarters. We will guide you when you reach Wuchang. It is expedient that we reach there quickly. Originally we meant to go to Canton and move overland from there, but someone had telephoned that we were aboard— Steeton, I suppose—and it became obvious we must go directly to our base, without pause. If Count von Bek had not objected to this plan, all trouble might have been averted.”

So Steeton had been on my side! In trying to save me and warn the authorities of all that was happening aboard

The Rover

, he had brought about this disaster and caused his own death.

It was horrible. Steeton had, in effect, died trying to save me. And now his killer was asking me to fly him to safety. But if I did not, others would die, too. Though some of them deserved death, they did not deserve to have it served to them in the manner which Shaw had hinted at. I sighed deeply and my shoulders sagged as I made my reply. All heroics seemed pointless now.

“I have your word that we shall not be harmed if I do as you wish?”

“You have my word.”

“Very well, General Shaw. I’ll fly your damned airship.”

“That’s very decent of you, old man,” said Shaw beaming and clapping me on the shoulder. He holstered his revolver.

W

hen I arrived on the bridge my horror was increased by the sight of the blood spattered everywhere on the floor, the bulkheads, the instruments. At least one person had been shot at close range—probably poor Barry. The coxswains were at their positions. They looked pale and shocked. Beside each coxswain stood two Chinese bandits, their bodies criss-crossed with bandoliers of bullets, their belts bristling with knives and small-arms. I had never in my life seen such a murderous gang as Shaw’s followers. No attempt had been made to clean the mess, and charts and log-tables were scattered about the bridge, some of them soaked in blood.

“I can do nothing until all this is cleaned up,” I said bleakly. Shaw said something in Cantonese and, very reluctantly, two of the bandits left the bridge to return with buckets and mops. As they worked, I inspected the instruments to make sure they were still in working order. Apart from some dents caused by bullets, nothing was badly damaged except the telephone, which looked to me as if it had been scientifically destroyed, perhaps by Steeton himself before he had made a run for the outer catwalk.

At last the bandits finished. Shaw gestured towards the main controls. We were flying very low at not much more than three hundred feet—a dangerous height.

“Put her up to seven hundred and fifty feet, height coxswain,” I said grimly. Without a word, the coxswain did as he was ordered. The ship tilted steeply and Shaw’s eyes narrowed, his hand going to his holster, but then we leveled out. I found the appropriate charts for China and studied them.

“I think I can get us to Wuchang,” I said. If necessary, we could always follow the railway line, but I doubted if Shaw was prepared to drop speed. He seemed anxious to get into his own territory by morning. “But before I begin, I want to be certain that Captain Korzeniowski and the others are still alive.”

Shaw pursed his lips and gave me a hard look. Then he turned on his heel. “Very well. Follow me.” Another order in Cantonese and a bandit fell into step behind me.

We reached the middle cabin and Shaw took a key from his belt, unlocking the door.

Three wretched faces stared up at us from the cabin. A crude bandage had been tied around Captain Korzeniowski’s head. It was soaked in blood. His face was ashen and he looked much older than the last time I had seen him. He did not appear to recognize me. His daughter was cradling his head in her lap. Her hair was awry and she seemed to have been crying. She offered Shaw a glare of hatred and contempt. Von Bek saw us and looked away.

“Are you—all right?” I asked rather foolishly.

“We are not dead, Mr. Bastable,” von Bek said bitterly, standing up and turning his back on us. “Is that what you meant?”

“I am trying to save your lives,” I said, a little priggishly under the circumstances, but I wanted them to know that a chap of my sort was capable of generosity towards his enemies. “I’m going to fly this ship to—General—Shaw’s base. He says he’ll not kill any of us if I do that.”

“His word’s hardly to be trusted after what’s happened tonight,” said von Bek. He gave a strange, harsh laugh. “Odd that you should find our politics so disgusting when you can throw in your lot cheerfully with him!”

“He’s scarcely a politician,” I pointed out. “Besides, it wouldn’t matter who he was. He holds all the cards—save the one I’m playing now.”

“Goodnight, Mr. Bastable,” said Una Persson, stroking her father’s head. “I think you mean well. Thank you.”

Embarrassed I backed out of the cabin and returned to the bridge.

B

y morning we had reached Wuchang and Shaw was evidently much more relaxed than he had been during the night. He went so far as to offer me a pipe of opium, which I instantly refused. In those days opium seemed pretty disgusting stuff.

Wuchang was quite a large city, but we passed it before it was properly awake, flying over terraced roofs, pagodas, little blue-roofed houses, while Shaw got his bearings and pointed out the direction in which we should go.

There is nothing like a Chinese sunrise. A great watery globe appeared over the horizon and the whole land was turned to soft tones of pink, yellow and orange as we approached a line of sand-coloured hills. I felt that we offended such beauty with our battered, noisy airship full of so many cut-throats of various nationalities.

Then we were flying over the hills themselves and Shaw told us to slow our speed. He issued more rapid orders in Cantonese and one of his men left the bridge and made for the ladder which would lead him onto the outer catwalk on the top of the hull. Plainly the man was to make some sort of signal that we were friendly.

Then, suddenly, we were over a valley. It was a deep, wide valley through which a river wound. It was a green, lush valley which seemed to have no business in that rocky landscape. I saw herds of cattle grazing. I saw small farmhouses, rice fields, pigs and goats.

“Is this the valley?” I asked.

Shaw nodded. “This is the Valley of the Morning. And look, Mr. Bastable—there is my ‘camp’...”

He pointed ahead. I saw high, white buildings, separated by patches of greenery. I saw fountains splashing and nearby were the tiny figures of children at play. Over this modern township there flew a large, crimson flag—doubtless Shaw’s battle flag. I was astonished to see such a settlement in these wilds and even more astonished to learn that it was Shaw’s headquarters. It seemed so peaceful, so civilized!

Shaw was grinning at me, wholly amused by my surprise.

“Not bad for a barbarian warlord, eh? We built it all ourselves. It has every amenity—and some which even London cannot boast.”

I looked at Shaw through new eyes. Bandit, pirate, murderer he might be—but he must be something more than these to have built such a city in the Chinese wilderness.

“Haven’t you read my publicity, Mr. Bastable? Perhaps you haven’t seen the

Shanghai Express

recently. They are calling me the Chinese Alexander! This is my Alexandria. This is Shawtown, Mr. Bastable!” He was chuckling like a schoolboy, delighted at his own achievements. “I built it.”

My first shock of amazement died away. “Perhaps you did,” I murmured, “but you built it from the flesh and bones of those you have murdered and painted it with the same crimson blood which stains your flag.”

“A rather rhetorical statement from you, Mr. Bastable. As it happens, I am not normally much of a hand at murder. I’m a soldier, really. You appreciate the difference?”

“I appreciate the difference, but my experience has shown me that you are not anything more than a murderer, ‘General’ Shaw.”

He laughed again. “We’ll see, we’ll see. Now—look over there. Do you recognize her? There—on the other side of the city? There!”

I saw her at last, her huge bulk moving gently in the wind, her mooring ropes holding her close to the ground. And I recognized her, sure enough.

“My God!” I exclaimed. “You’ve got the

Loch Etive

!”

“Yes,” he said eagerly, again like a schoolboy who has added a rather good new stamp to his collection. “That’s her name. She’s to be my flagship. At this rate I’ll soon have my own air fleet. What d’you think of that, Mr. Bastable? Soon I’ll control not only the ground, but the air as well. What a warlord I shall be! Something

of

a warlord, eh?”

I stared at his eager, glowing face and I could think of no reply. He was not mad. He was not naive. He was not a fool. He was, in fact, one of the most intelligent men I had ever encountered. He baffled me absolutely.

He had thrown back his head and was laughing joyfully at his own cleverness—at his own wholly gargantuan act of cheek in stealing what was perhaps the finest and biggest aerial liner in the skies!

“Oh, my sainted aunt!” His half-Chinese features were still creased with mirth. “What larks, Mr. Bastable! What larks!”