The Warlord of the Air (19 page)

Read The Warlord of the Air Online

Authors: Michael Moorcock

Chi’ng Che’eng Ta-Chia

T

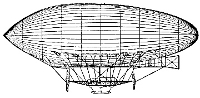

here were no mooring masts on the flat space outside the city and so ropes had to be flung down to waiting men who manhandled the ship until the gondola touched the ground. Then cables and ropes were pegged into the earth, holding

The Rover

as, further away, the

Loch Etive

was held.

As we disembarked, under the suspicious gaze of Shaw’s armed bandits, I expected to see coolies come hurrying up to strip the ship of its cargo, but the men who arrived were healthy, well-dressed fellows whom I first mistook for clerks or traders. Shaw had a word with them and they began to go aboard the airship, showing no subservience of the sort normally shown to bandit chieftains by their men. In fact the pirates who disembarked with their guns and knives and bandoliers, their ragged silks, sandals and beaded headbands, looked distinctly out of place here. Shortly after landing, they climbed into a large motor wagon and steamed away towards the far end of the valley. “They go to join the rest of the army,” Shaw explained. “Chi’ng Che’eng Ta-Chia is primarily a civilian settlement.”

I was helping Captain Korzeniowski, supporting one elbow while Una Persson supported the other. Von Bek strode moodily ahead of us as we moved towards the town. Korzeniowski was better today and his old intelligence had returned. Behind us streamed the crewmen of

The Rover

, looking about them in open amazement.

“What was the name you used?” I asked the ‘General’.

“Chi’ng Che’eng Ta-Chia—it’s hard to translate. The name of the city yonder.”

“I thought you called it Shawtown.”

He burst into laughter again, his great frame shaking, his hands on his hips. “My joke, Mr. Bastable! The place is called— well—Democratic Dawn City, perhaps? Dawn City Belonging to Us All? Something like that. Call it Dawn City, if you like. In the Valley of the Dawn. The first city of the New Age.”

“What New Age is that?”

“Shuo Ho Ti—his New Age. Do you want the translation of my Chinese name, Mr. Bastable? It is ‘One Who Makes Peace’— The Peacemaker.”

“Now that isn’t a bad joke at all,” I said grimly as we strode over the grass towards the first tall, elegant buildings of Dawn City. “Considering that you’ve just murdered two English officers and stolen a British airship. How many people did you have to kill to get your hands on the

Loch Etive

?”

“Not many. You must meet my friend Ulianov—he will tell you that the ends justify the means.”

“And what exactly are your ends?” I grew impatient as Shaw flung an arm round my shoulders, his bland oriental face beaming.

“First—the Liberation of China. Driving out all foreigners— Russians, Japanese, British, Americans, French—all of them.”

“I doubt if you’ll manage it,” I said. “And even if you did, you’d probably starve. You need foreign money.”

“Not really. Not really. Foreigners—particularly the British with their opium trade—ruined our economy in the first place. It will be hard to build it up again alone, but we shall do it.”

I said nothing to this. His were evidently messianic dreams, not unlike those of old Sharan Kang—he believed himself much more powerful than he actually was. I almost felt sorry for him then. It would only take a fleet of His Majesty’s aerial battleships to turn his whole dream into a nightmare. Now that he had committed acts of piracy against Great Britain he had become something more than a local problem to be dealt with by the Chinese authorities.

As if reading my thoughts, he said, “The passengers and crew of the

Loch Etive

make useful hostages, Mr. Bastable. I doubt if we’ll be attacked by your battleships immediately, eh?”

“Perhaps you’re right. What are your plans

after

you have liberated all China?”

“The world, of course.”

It was my turn to laugh. “Oh, I see.”

He smiled a secret smile, then. “Do you know who lives in Dawn City, Mr. Bastable?”

“How could I? Members of your government-to-be?”

“Some of those, yes. But Dawn City is a town of outlaws. There are exiles here from every oppressed country in the world. It is an international settlement.”

“A town of criminals?”

“Some would call it that.” We were now strolling through wide streets flanked by willows and poplars, grassy lawns and bright beds of flowers. From the open window of one of the houses drifted the sound of a violin playing Mozart. Shaw paused and listened, the crew of

The Rover

coming to a straggling halt behind us. “Beautiful, isn’t it?”

“Very fine. A phonograph?”

“A man. Professor Hira. He’s an Indian physicist. Because of his nationalist sympathies he was put in prison. My men helped him escape and now he is continuing his research in one of our laboratories. We have many laboratories—many new inventions. Tyrants hate original thinking. So the original thinkers are driven to Dawn City. We have scientists, philosophers, artists, journalists—even a few politicians.”

“And plenty of soldiers,” I said harshly.

“Yes, plenty of soldiers—lots of guns and stuff,” he said vaguely as if slightly put out by my interruption.

“And it will all be wasted,” said von Bek suddenly, turning to look back at us. “Because you wish to control too much power, Shaw.”

Shaw waved a languid hand. “I have been lucky in that, Rudy. I have the power. I must use it.”

“Against fellow comrades. I was expected in Brunei. A revolt was planned. Without me there to lead it, it would have collapsed. It must have collapsed by now.”

I stared at him. “You know each other?”

“Very well,” von Bek said angrily. “Too d⸺’d well.”

“Then you, too, are a socialist?” I said to Shaw.

Shaw shrugged. “I prefer the term communist, but names don’t matter. That is von Bek’s trouble—he cares about names. I told you, Rudy, that the British authorities were waiting to arrest you, that the Americans already knew there was something suspicious about

The Rover

when you reached Saigon. Your telephone operator must have been sending out secret messages to them. But you wouldn’t listen—and Barry and the telephone man died because of your obstinacy!”

“You had no right to take over the ship!” shouted the Saxon count. “No right at all.”

“If I had not, we should all be in some British jail by now— or dead.”

Korzeniowski said weakly, “It’s all over. Shaw has presented us with a

fait accompli

and there it is. But I wish you had better control over your men, Shaw... Poor Barry wouldn’t have shot you, you know that.”

“They

didn’t know it. My army is a democratic army.”

“If you’re not careful they’ll destroy you,” Korzeniowski continued. “They serve you only because they consider you the best bandit in China. If you try to discipline them, you’ll find them cutting your throat.”

Shaw accepted this. He led the way up a concrete path towards a low pagoda-style building. “I do not intend to rely on them much longer. As soon as my air fleet is ready...”

“Air fleet!” snorted von Bek. “Two ships?”

“Soon I’ll have more,” Shaw said confidently. “Many more.”

We entered the cool gloom of a hallway. “It is old-fashioned to rely on armies, Rudy,” Shaw continued. “I rely on science. We have many projects nearing fruition—and if Project NFB is successful, then I think I’ll disband the army altogether.”

“NFB?” Una Persson frowned. “What’s that?”

Shaw laughed. “You are a physicist, Una—the last person I should tell anything to at this stage.”

A European in a neat, white suit appeared in the hallway. He smiled at us in welcome. He had grey hair, a wrinkled face.

“Ah, Comrade Spender. Could you accommodate these people here for a while?”

“A pleasure, Comrade Shaw.” The old man walked to a section of the blank wall and passed his hand across it. Instantly a series of rows of coloured lights appeared on the wall. Some of them were red, but most were blue. Comrade Spender studied the blue lights thoughtfully for a moment then turned back to us. “We have the whole of Section Eight free. One moment, I’ll prepare the rooms.” He touched a bank of blue lights and they changed to red. “It is done. All operating now.”

“Thank you, Comrade Spender.”

I wondered what this peculiar ritual could mean.

Shaw led us down a corridor with wide windows which looked out onto a forecourt in which several fountains were playing. The fountains were in the latest styles of architecture— not all entirely to my taste. We came to a door with a large figure eight stenciled on it. Shaw pressed his hand against the numeral and said: “Open!” At once the door slid upwards, disappearing into the ceiling. “You’ll have to share rooms, I’m afraid,” said Shaw. “Two of you in each room. There’s everything you need and you can communicate any other wants by means of the telephones you’ll find. Goodbye for now, gentlemen.” He turned and the door slid down behind him. I went up to it and put my palm against it.

“Open!” I said.

As I expected nothing happened. Somehow the door was keyed to recognize Shaw’s hand and voice! This certainly was a city of scientific marvels.

After some discussion and a general pacing about and testing of the windows and doors we realized there was no easy means of escape.

“You’d better share a room with me, I suppose,” said von Bek, tapping me on the shoulder. “Una and Captain Korzeniowski can go next door.” The crewmen were already entering their rooms, finding that the doors opened and shut on command.

“Very well,” I said distastefully.

We entered our room and found that there were two beds in it, a writing desk, wardrobes, chests of drawers, bookshelves filled with a wide variety of fiction and non-fiction, a telephone communicator and something with a milky-blue surface which was oval in shape and unidentifiable. Our windows looked out onto a sweet-scented rose garden, but the glass was unbreakable and the windows could only be opened wide enough to let in the air and the scent. Pale blue sleeping suits had been laid on the beds. Ignoring the suit, Rudolf von Bek flung himself on the bed fully clothed, turning his head and giving me a bleak smile.

“Well, Bastable, now that you’ve met a real, full-blooded revolutionary, I must look pretty pale in comparison, eh?”

I sat down on the edge of the bed and began to remove my boots which were pinching. “You’re as bad,” I said. “All that makes Shaw different from you is his madness which is that much grander—and a thousand times more foolish! At least you confined your activities to what was possible. He dreams of the impossible.”

“That’s what I like to think,” von Bek said seriously. “But there again—he’s built Dawn City up a lot since I was last here. And one would have thought it impossible to steal a liner the size of the

Loch Etive.

And there’s no doubting that his scientific gadgets—this whole apartment building for instance—are in advance of anything which exists in the outside world.” He frowned. “I wonder what Project NFB could be?”

“I don’t care,” I said. “My only wish is to get back to the civilization I know—a sane world where people behave with a reasonable degree of decency!”

Von Bek smiled patronizingly. Then he sat up and stretched. “By God, I’m hungry! I wonder if we get any food?”

“Food,” said a voice from nowhere. I watched, fascinated, as a face appeared in the milky-blue oval. It was a Chinese girl. She smiled and continued. “What would you like to eat, gentlemen? Chinese food—or European?”

“Let’s have some Chinese food, by all means,” said von Bek without consulting me. “I’m very fond of it. What have you got?”

“We will send you a selection.” The girl’s face vanished from the screen.

A few moments later, while we were still recovering from that experience, a section of the wall opened to reveal an alcove in which sat a tray piled high with all kinds of Chinese delicacies. Eagerly von Bek sprang up, seized the tray and placed it on our table.

Forgetting for an instant everything but the mouth-watering smell of the food, I began to eat, wondering, not for the first time, if this were not perhaps some fantastically detailed dream induced by Sharan Kang’s drugs.

Vladimir Ilyitch Ulianov

A

fter eating I washed, dressed myself in the sleeping suit and climbed beneath the quilt covering the bed. The bed was the most comfortable I had ever slept in and soon I was fast asleep.

I must have slept through the rest of the day and the whole of the night, for I awoke the next morning feeling utterly splendid! I was able to look back on the events of the past few days with a philosophical acceptance I found surprising in myself. I still believed Korzeniowski, von Bek, Shaw and the rest totally misguided, but I could see that they were not inhuman monsters. They really believed they were working for the good of people they considered to be “oppressed”.

I was feeling so rested I wondered if perhaps the food had been drugged but when I turned my head I saw that von Bek had evidently not slept as well. His eyes were red-rimmed and he was still in his outdoor clothes, his hands behind his head, staring moodily at the ceiling.