The Warlord of the Air (7 page)

Read The Warlord of the Air Online

Authors: Michael Moorcock

Then, suddenly, something dropped from the ship. I was struck savagely in the face and smashed backwards against the rock. I gasped for breath, unable to understand the reason for the attack or, for that matter, what missile had been used.

Blinking, I sat up and peered around me. For yards in all directions the ruins glistened wetly—and there were several huge puddles now in evidence. I was soaked through. Was this some rather bad joke at my expense—their way of telling me that I needed a bath? It seemed unlikely. Shakily, I got up, half-expecting the airship to send down another mass of water.

But then I realized that the vessel was sinking rapidly towards the ruins, looming low in the sky, still sounding its siren. It was lucky for me it had not carried sand as ballast—for ballast was what that water had been! Much lightened, the balloon was able to come to my assistance with less risk to itself.

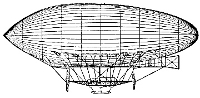

Soon it was little more than twenty feet above me. I stared hard at the slogan on its side, at the Union Jacks on its tail-fins. There was no question of its reality. I had once seen an airship flown by Mr. Santos-Dumont, but it had been a crude affair compared with this giant. There had been a great deal of progress in the last couple of years, I decided.

Now a circular hatch was opened in the bottom of the metal gondola and amused British faces peered over the lip.

“Sorry about the bath, old son,” called one in familiar Cockney tones, “but we did try to warn you. Understand English?”

“I

am

English!” I croaked.

“Blimey! Hang on a minute.” The face disappeared.

“All right,” said the face, reappearing. “Stand clear there.”

I stepped back nervously, expecting another drenching, but this time a rope ladder snaked down from the hatch. I ran forward and grabbed it in relief but as soon as my hand clasped the first rung I heard a yell from overhead:

“Not yet! Not yet! Oh, Murphy, the idiot! The—”

I missed the rest of the oath for I was being dragged over the rocks until I managed to let go of the rung and fall flat on my face. The flying machine had yawed round a fraction in the sky—a fraction being a good few feet—and laid me low for a second time! I got up and did not attempt to grab the rope ladder again.

“We’ll come down,” shouted the face. “Stay where you are.”

Soon two smartly dressed men clambered from the hatch and began to descend the ladder. They were dressed in white uniforms very similar to those worn by sailors in the tropics, though their jackets and trousers were edged with broad bands of light blue and I did not recognize the insignia on their sleeves. I admired the casual skill and speed with which they climbed down the swaying ladder, paying out a rope which led upwards into the ship. When they were a few rungs above me they tossed me the rope.

“Easy now, old son,” called the man who had originally addressed me. “Tie this round you—under your arms—and we’ll take you up! Understand?”

“I understand.” Swiftly I obeyed his instructions.

“Are you secure?” called the man.

I nodded and took a good grip on the rope.

The sky ‘sailor’ signaled to an unseen shipmate. “Haul away, Bert!”

I heard the whine of a motor and then I was being dragged upwards. At first I began to spin wildly round and round and felt appallingly sick and dizzy until one of the men on the ladder leaned out and caught my leg, steadying my ascent.

After what must have been a minute but which seemed like an hour I was tugged over the side of the hatch and found myself in a circular chamber about twelve feet in diameter and about eight feet high. The chamber was made entirely of metal and rather resembled a gun-turret in a modern ironclad.

The small engine-driven winch which had been the means of bringing me up was now switched off by another uniformed man, doubtless “Bert”. The other two clambered aboard, gathered in the rope ladder in an expert way, and shut the hatch with a clang, bolting it tight.

There was one other man in the chamber, standing near an oval-shaped door. He, too, was dressed in ‘whites’, but wore a solar topee and had major’s pips on the epaulettes of his shirt. He was a smallish man with a sharp, vulpine face, a neat little black moustache which he was smoothing with the end of his swagger stick as he peered at me, poker-faced.

After a pause, while his large, dark eyes took in my appearance from head to toe, he said: “Welcome aboard. English are you?”

I finished removing the rope from under my arms and saluted. “Yes, sir. Captain Oswald Bastable, sir.”

“Army, eh? Bit odd, eh? I’m Major Powell, Royal Indian Air Police—as you’ve probably noticed, what? This is the patrol ship

Pericles.”

He scratched his long nose with the edge of his stick. “Amazin’—amazin’. Well, we’ll talk later. Sick Bay for you first, I’d say, what?”

He opened the oval door and stood aside while the two men helped me through.

I now found myself in a long passageway, blank on one side but with large portholes on the other. Through the portholes I could see the ruins of Teku Benga slowly falling away below us. At the end of the passage was another door and, beyond the door, a corner into a shorter passage on both sides of which were ranged more doors bearing various signs. One of the signs was sick bay.

There were eight beds inside, none of which was occupied. There were all the facilities of a modern hospital, including several gadgets at whose use I could not begin to guess. I was allowed to undress behind a screen and take a long bath in the tub I found there. Feeling much better, I got into the pair of pyjamas (also white and sky blue) provided and made my way to the bed which had been prepared up at the far end of the room.

I was in something of a trance, I must admit. It was difficult to remember that I was in a room which at this moment was probably floating several hundred feet or more above the mountains of the Himalayas. Occasionally there was a slight motion from side to side or the odd bump, such as one might feel on a train, and, in fact, it did rather feel as if I were on a train—a rather luxurious first-class express, perhaps.

After a few minutes the ship’s doctor entered the room and had a few words with the orderly who was folding up the screens. The doctor was a youngish man with a great round head and a shock of red hair. When he spoke it was in a soft Scottish accent.

“Captain Bastable is it?”

“That’s right, doctor. I’m all right, I think. In my body, at any rate.”

“Your body? What d’you think’s wrong with your head?”

“Frankly, sir, I think I’m probably dreaming.”

“That’s what

we

thought when you were first spotted. How on earth did you manage to get into those ruins? I thought it was impossible.” As he spoke he checked my pulse, looked at my eyes and did the usual things doctors do to you when they can’t find anything specifically wrong.

“I’m not sure you’d believe me, doctor, if I told you I rode up on horseback,” I said.

He gave a peculiar laugh and stuck a thermometer into my mouth. “No, I don’t think I would! Rode up! Ha!”

“Well,” I said cautiously, after he had removed the thermometer. “I did ride up there.”

“Aye.” Plainly he didn’t believe me. “Possibly you think you did. And the horse jumped that chasm, did it?”

“There wasn’t a chasm there when I went there.”

“No chasm—?” He laughed aloud. “My stars! No chasm! There’s always been a chasm there—for a damned long time, at any rate. That’s why we were flying over the ruins. The only way to reach them is by airship. Major Powell’s a bit of an amateur archaeologist. He’s got permission to reconnoitre this area with a view to exploring Teku Benga some time. He knows more about the lost civilizations of the Himalayas than anyone. He’s a scholar, our Major Powell.”

“I’d hardly count Kumbalari as a

lost

civilization,” I said. “Not in the strict sense. That earthquake could only have happened a couple of years ago, surely. That’s when I went there.”

“Two years ago? You’ve been in that God-forsaken place for two years? You poor fellow. But you’re remarkably fit on it, I’ll say that.” He frowned suddenly. “Earthquake? I haven’t heard of an earthquake in Teku Benga. Mind you...”

“There hasn’t been an earthquake in Teku Benga in living memory.” It was the sharp, precise voice of Major Powell, who had come in as we talked. He looked at me with a certain wary curiosity. “And I very much doubt that anyone could live there for two years. There’s nothing to eat, for one thing. On the other hand, there’s no other explanation as to how you got there— unless a private expedition I haven’t heard about

flew

there two years ago.”

It was my turn to smile. “Hardly likely, sir. No ship of this kind existed two years ago. In fact, it’s remarkable how...”

“I think you had better check him up here, Jim,” said Major Powell tapping his head with his stick. “The poor chap’s lost all sense of time—or something. What was the date when you left for Teku Benga, Captain Bastable?”

“June twenty-fifth, sir.”

“Um. And what year?”

“Why, 1902, sir.”

The doctor and the major stared at each other in some concern.

“That’s when the earthquake happened, all right,” Major Powell said quietly. “1902. Almost everyone killed. And there

were

some English soldiers there... Oh, by God! This is ridiculous!” He returned his attention to me. “You are in a serious condition, young man. I wouldn’t call it amnesia—but some sort of false memory. Mind playing you tricks, um? Maybe you’ve read a lot of history, eh, like me? Perhaps you’re an amateur archaeologist, too? Well, I expect we can soon cure you and learn what really happened.”

“What’s so odd about my story, major?”

“Well, for one thing, old chap, you’re a bit too well-preserved to have gone up to Teku Benga in 1902. That was over seventy years ago. This is July the fifteenth. The year, I’m afraid, is 1973. A.D., of course. Does that ring a bell?”

I shook my head. “Sorry, major. But I’ll agree with you on one thing. I’m obviously completely insane.”

“Let’s hope it’s not permanent,” smiled the doctor. “Probably been reading a bit too much H.G. Wells, eh?”

My First Sight of Utopia

E

vidently out of a mistaken sense of kindness, both the doctor and Major Powell left me alone. I had received a hypodermic injection containing some kind of drug which made me drowsy, but I could not sleep. I had become totally convinced now that some peculiar force in the catacombs of the Temple of the Future Buddha had propelled me through Time. I

knew

that it was true. I

knew

that I was not mad. Indeed, if I were mad, then there would be little point in fighting such a detailed and consistent delusion—I might just as well accept it. But now I wanted more information about the world into which I had been plunged. I wanted to discuss the possibilities with the doctor and the major. I wanted to know if there were any evidence of such a thing having happened before—any unexplained reports of men who claimed to have come from another age. At this thought I became depressed. Doubtless there

were

other accounts. And doubtless, too, those men had been considered mad and committed to lunatic asylums, or charlatans and committed to prison. If I were to remain free to see more of this world of the future, to discover, if I could, a means of returning to my own time, then it would not do for me to make too strong a claim for the truth. It would be better for me to affect amnesia. That they would understand better. And if they could invent an explanation as to how I came to be in the ruins of Teku Benga seventy years after the last man had been able to set foot there, then good luck to them!

Feeling much happier about the whole thing, having made my decision, I settled back in the pillows and fell into a doze.

T

he ship’s about to land, sir.”

It was the voice of the orderly which wakened me from my trance. I struggled up in the bed, but he put a restraining hand on me. “Don’t worry, sir. Just lie back and enjoy the ride. We’re transferring you to the hospital as soon as we’re safely moored. Just wanted to let you know.”

“Thanks,” I said weakly.

“You must have been through it, sir,” said the orderly sympathetically. “Mountain climbing is a tricky business in that sort of country.”

“Who told you I’d been mountain climbing?”

He was confused. “Well, nobody, sir. We just thought... Well, it was the obvious explanation.”

“The obvious explanation? Yes, why not? Thank you again, orderly.”

He frowned as he turned away. “Don’t mention it, sir.”

A

little while later they began to remove the bolts which had fixed the bed to the deck. I had hardly been aware—save for a slight sinking sensation and a few tremors—that the ship had landed. I was wheeled along the corridors until we reached what I guessed to be the middle of the ship. Here huge folding doors had been lowered to form steps to the ground and a ramp had been laid over the steps to make it possible to wheel my bed down.

We emerged into clear, warm air and the bed bumped a trifle as it was wheeled over flattened grass to what was plainly a hospital van, for it had large red crosses painted on its white sides. The van was motorized, by the look of it. There were no horses in evidence. Glancing around me I received my second shock of pure astonishment at the sight which now met my gaze. Dotted about a vast field were a number of towers, smaller than, but strongly resembling, the Eiffel Tower in Paris. About half of these towers were in use—great pyramids of steel girders to which were moored the best part of a dozen airships, most of which were considerably larger than the giant in which I had been brought! It was obvious that not all the flying monsters were military vessels. Some were commercial, having the names of their lines painted on their sides and decorated rather more elaborately than, for instance, the

Pericles

.