The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (14 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Accounts of Alaska’s brute beauty were also extremely popular as Roosevelt was coming of age. Virtually no important biologists had inventoried this American acquisition. Back in 1867, Secretary of State William Seward had acquired more than 650,000 square miles of Alaska from Russia for a song—$7.2 million (less than 2 cents an acre).

40

Antiexpansionists called the purchase “Seward’s Folly” and considered it a frozen wasteland not worth a trillionth of a dollar, but other Americans cheered it. Determined to prevent both the Russians and the Japanese from killing what were now American seals in the Bering Sea rookeries, President Grant set aside the Pribilof Islands to protect them in 1869; this measure was approved by Congress the following year.

Living on the five tiny Pribilof Islands—only two of which, Saint Paul and Saint George, were habitable by humans—were the finest seal herds in the world, tens of thousands of bulls with harems swimming in the frigid fogbound waters and coming onto rocky beaches. The Pribilof Islands were, in essence, cities of seals. But Russian, American, and Japanese vessels were slaughtering these mammals in the Bering Sea at a rapid rate. To these hunters and harpooners, the Pribilofs were a killing ground.

Rudyard Kipling included in his second

Jungle Book

the short story “The White Seal,” about fierce battles between nations over seal fur from the Bering Sea. Now that the United States owned these islands—considered the most lucrative rookeries of fur mammals anywhere—President Grant wanted to make sure he could protect the hundreds of thousands of fur seals.

41

Like Grant, President Benjamin Harrison also cast an eye on Alaska. By means of an Executive Order on March 30, 1891, he created the Afognak Island Forest and Fish Culture Reserve to protect another part of Alaska’s “bays and rocks and territorial waters, including among others the sea lion and sea otter islands.”

42

(The island is today part of Katmai National Monument, the second-largest area in the National Park System.

43

) A side effect of Harrison’s executive action on behalf of Alaskan wildlife was that the thick-billed murres and red-legged kittiwakes were saved from extinction. Flocks of auklets were able to flourish, and the blue-gray arctic fox could continue devouring their eggs. The food chain had been preserved.

44

Neither Grant nor Harrison has been properly credited for small steps in protecting Alaskan wildlife from harpooners and market hunters. As Roosevelt later noted, the foresight of his two fellow Republican presidents regarding Alaskan wildlife had mattered. It proved that the federal government could, when necessary, intervene effectively to help mammals survive as species. Also, it showed that the government would protect the intricate tapestry of nature if the reason for doing so was economically compelling—in the case of Yellowstone, wildlife was being protected for tourism; in Alaska, the motivation was the long-term benefit of the seal-hunting industry.

This economic conservationism was a postulation that T.R.’s uncle Robert Barnwell Roosevelt—who lived in a brownstone adjacent to T.R.’s birthplace on Twentieth Street in New York City—put to the test regarding the fished-out streams and lakes of North America.

III

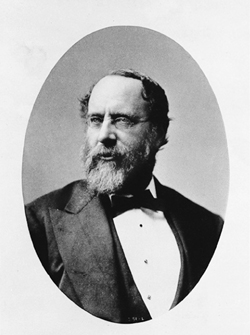

As a boy Theodore Roosevelt always had a soft spot for Robert Barnwell Roosevelt, his vaguely bohemian “Uncle Rob.” A creative contrarian and lover of animals, birds, and especially fish, Uncle Rob was always caught up in the maelstrom of his times. He simply never sat upright in his carriage. With a bristle-cropped beard, receding hairline, bad eyesight, and frameless spectacles, R.B.R. (as the family called him) would be easy to mistake for any of the bewhiskered American presidents elected be

tween Grant and McKinley. Imbued with an outlandish catholicity of interests, the conspicuous Robert B. Roosevelt epitomized the many-sided Victorian-era bon vivant. For decades the Roosevelt family—owing to his philandering with chorus girls and trollops—treated him as a black sheep. Somehow he just couldn’t control his streak of lechery. Embarrassed by his wayward morals and intellectual incongruities the family, to some extent, banished R.B.R. from the fold. Nevertheless, his shiftiness aside, he was greatly admired in his day by the public at large.

45

Robert B. Roosevelt was considered the great U.S. conservationist during the years from the Civil War to the Spanish-American War. “Uncle Rob,” as his nephew Theodore Roosevelt called him, was a many-sided Victorian reformer. In recent years the New York Historical Society (manuscript Department) has opened R.B.R.’s personal scrapbooks for scholarly viewing.

Robert B. Roosevelt. (

Courtesy of the Theodore Roosevelt Association

)

While not quite a bigamist, Robert B. Roosevelt came awfully close to being one. The simple fact was that he led a double life, married to Elizabeth Ellis Roosevelt (T.R.’s Aunt Lizzie) while having a long-standing affair with a neighbor, Minnie O’Shea (Mrs. Robert F. Fortescue), whom he hired at the

New York Citizen

.

46

Secretly R.B.R. fathered four children with this mistress. Later, after Elizabeth died, he married Minnie.

47

Unfortunately, this affair was so widely frowned upon that Robert B. Roosevelt has not been fully appreciated by recent environmental historians. His diaries and papers were largely hidden by the Roosevelt family for 100 years. Usually R.B.R. sported a porkpie hat and a gray jacket as he squired women around town. As a kind of territorial marker he gave elegant green gloves—purchased in bulk at A.T. Stewart’s department store—to the women he slept with. Society types used to laugh whenever they walked down Fifth Avenue or rode a carriage in Central Park

and spied a woman wearing these gloves, which might as well have been the Scarlet Letter.

48

Apparently, these women didn’t realize the negative connotation of the gloves.

But R.B.R.’s womanizing was, in truth, the least interesting aspect of him. To many it seemed that he had distinct parts and switched roles dexterously. Casting off and putting on personas, he could be a barroom enthusiast, a romantic adventurer, a barrister, a rousing orator, a husband, an adulterer, a sage, an animal protection advocate, a gourmet cook, a humble farmer—R.B.R. could even write memorable prose as a novelist and satirist. As was typical of the British upper class, Robert, never in need of money, dedicated himself to public service.

49

Known for switching jobs with kaleidoscopic quickness, he served as coeditor of the reformist newspaper

New York Citizen

(which rallied its readers against the nefarious William Marcy Tweed’s ring).

50

He was one of the Committee of Seventy, which broke the Tweed ring, causing the notorious boss to leave public life in disgrace.

During the Civil War R.B.R. served in a New York volunteer regiment; this experience provided him with enduring friendships. During Reconstruction he took his gusto for reform into the political sphere in 1870 and was elected to Congress; the only reason he ran was to establish federal fish hatcheries. Following a successful two-year stint in Washington, D.C., promoting pisciculture, he wrote plays and became commissioner of the Brooklyn Bridge (1879–1881), overseeing architectural adjustments and maintenance issues. As U.S. minister to the Netherlands under President Grover Cleveland in 1888, Roosevelt was at his smooth-functioning best in promoting a special “Dutch-American” relationship. Extremely adept at fund-raising, he served as treasurer of the Democratic National Committee in 1892, helping elect Cleveland for a second (nonconsecutive) presidential term.

51

Erudition came easily to Robert B. Roosevelt. A self-styled man of letters, he wrote one mediocre novel—

Love and Luck

(1880)—which didn’t sell well. But his comic satire

Five Acres Too Much

(1869), which spoofed the virtues of farming, struck a chord in the immediate post–Civil War years, when laughs were in short supply.

52

His other offbeat novel,

Progressive Petticoats

(1874), a lampoon of women suffragists, was also enthusiastically received. (For a modern-day comparison, he was the David Lodge of his generation). His pasquinades had ardent fans. As a personal favor, Robert B. Roosevelt also edited the flowery poetry of General Charles G. Halpine (Miles O’Reily), his coeditor at the

New York Citizen

.

53

Sometimes R.B.R. wrote limericks himself—which were topical, like most ef

forts in this genre, and uniformly bad. On the whole, Roosevelt’s literary efforts, read a century after they were written, no longer sparkle; posterity has thrown them overboard. Only occasionally does his wit hold up. But R.B.R.’s furious advocacy of “fish rights,” the nonprofit sine qua non that became his sustainable legacy, has enduring historical importance, though it has been undervalued by academic scholars.

54

R.B.R., more than any other direct influence, turned Theodore Roosevelt into a conservationist as a teenager.

Born on August 27, 1829, Robert B. Roosevelt grew up in New York City. Turning his back on the mercantile life of his father, Cornelius V. S. Roosevelt, and the Quakerism of his mother, Margaret Barnhill Roosevelt, R.B.R. became a maverick who gravitated toward the pageantry of wild things.

55

Later in life Hamilton Fish—who had served as governor of New York and Grant’s secretary of state—dubbed R.B.R. “Father of all the Fishes.”

56

Robert’s unconventionality first became clear when he changed his middle name, Barnhill, to Barnwell to avoid jokes about manure. As a teenager, he fished the briny waters of Long Island Sound for striped bass and bluefish whenever the opportunity presented itself. College, however, wasn’t important to the short, portly R.B.R. For all his erudition, he was happiest outdoors, whether at sea or on land. He flouted civil niceties, always speaking his mind candidly. Even his enemies—and there were many—couldn’t deny that he was frank.

When Robert turned twenty-one years old, he married Elizabeth Ellis and embarked on a political career as a Democrat. His decision to remain a Democrat, even after Abraham Lincoln walked onto the national stage, cast a lingering haze of suspicion over him in family circles. In aggregate, the reason R.B.R. gave for not following the family line was the galloping tempo, unhampered corruption, and rake-offs that characterized New York politics in the late 1850s and 1860s. Democrats, he believed, while fools, were less beholden to robber barons, and that made all the difference to him.

57

Like other New York gallants Robert B. Roosevelt belonged to the so-called club set of the late 1850s. With corks popping, often overdrinking and straining his constitution, he enjoyed discussing political, literary, and culinary affairs. R.B.R., in fact, developed a virtual mania for joining elite “societies,” perhaps because he was very sociable. Robert (or “Rob” as he was usually called) was very everything, in fact. Very blue-blooded, though he aspired to be a populist. Very mannered, though he used the rake’s characteristic tactics of cajolery and the nod and the wink. As a gourmet chef

he proudly founded the Pot Luck Club, whose intellectual members cooked five-star meals, judged truffles, and drank the finest French wines. Every year he also chaired the annual dinner of the Ichthyophagous Club, helping educate aspiring gourmets about the “unsuspected excellence” of many neglected varieties of American fish. Usually, the naturalist Joaquin Miller (whom he called the “sweet singer of the Sierras”) was at his side. Fishing stories in a comical vein were told at these dinners. The British, R.B.R. used to say, while always filling the champagne glasses, had to learn there was more to life than cod. The roomful of fish lovers roared with delight. A few specialty dishes were

Darne de saumon, garni d’éperlans à la Roosevelt

and

Filet of striped bass with shrimps à la Baird.

58

Perhaps more than anybody else in his era, Robert B. Roosevelt argued for fish conservation because he enjoyed eating perch and trout so much. Turtle soup was another one of his specialties. Writing in his diary of the “turtle trial,” in fact, Robert was a contrarian, considering both Henry Bergh and the judge flat wrong. Sea turtles, he believed, weren’t insects or reptiles, but fish. Deeming the Pot Luck Club the “very head and centre of gastronomic, ichthyologic, zoo-logic,” he declared turtle too delicious a culinary delight to be an insect. “Then we have the sea turtle,” he wrote, “the glorious monster who sleeps in the mid-ocean in the amplitude of his thousand pounds of excellence.” Just hearing all that talk about sea turtles during the turtle trial, in fact, made R.B.R. want to “luxuriate in the green fat and the yellow fat.” Only an imbecile, he scoffed, could possibly eat turtles thinking they were insects or reptiles. “It had been claimed that turtles are snakes developed in Darwinian theory,” he recorded. “That a very intelligent and highly gifted snake, feeling sensitively the unprotected nature of a tail that dragged its slow length an unnecessary distance behind by taking much though added a shell to his body and converted the longest and slimmest of figures into the stoutest and roundest. That a turtle, and above all a snapping turtle, is but a snake in disguise…. I, for my part, cannot accept a serpent when I ask for a turtle; I repudiate the ‘snaix’ even under the head of a terrapin. Why should not a turtle be a fish?”

59