The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (110 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Furthermore, Roosevelt believed that Pinchot was doing a superb job of finding innovative ways to put out wildfires, both man-made and natural, which swept over the West in the summertime. He deserved an ovation. Wildfires were most common in zones where the terrain was moist for nine months of the year but then became extremely dry from July through September, creating a tinderbox. When scrub, leaves, twigs, or branches dried out, they became highly flammable. Entire national forests could be transformed almost instantly into smoldering mulch. Sometimes farmers would use fire (circumscribed burning) to clear land. This was often necessary, but it was dangerous. If a light wind picked up the flames and sparks jumped, they could cause an uncontrollable wildfire. Lightning fires were another problem for the dense forests and wind-beaten sagebrush of the West. An entire forest reserve could disappear in a few days. The chaparral in southern California and the lower-elevation deserts in the Southwest were particularly vulnerable to wildfires. Then, of course, there was human carelessness, as well as arson.

68

What Roosevelt had on his hands in 1906, however, was a feud between forest rangers and stockmen in the western wildlands. To reduce tension Roosevelt formed Forest Service advisory committees aimed at enlightening ranchers on why a steady stream flow and reservoirs were directly correlated with

more

grass for grazing. Forest rangers were their friends, not the enemy. Meanwhile, the USDA’s Biological Survey increased its predator control, teaching ranchers that poisoning coyotes was smart but shooting insect-eating songbirds was a mistake.

“There is therefore no longer an excuse for saying that the reserves retard the legitimate settlement and development of the country,” Roosevelt wrote to Pinchot in a letter intended for public distribution.

“The forest policy of the Government in the West has now become what the West desired it to be. It is a national policy, wider than the boundaries of any State, and larger than the interests of any single industry. Of course it cannot give any set of men exactly what they would choose. Undoubtedly the irrigator would often like to have less stock on his watersheds, while the stockman wants more. The lumberman would like to cut more timber, the settler and the miner would often like him to cut less. The county authorities want to see more money coming in for schools and roads, while the lumberman and stockman object to the rise in the value of timber and grass. But the interests of the people as a whole are, I repeat, safe in the hands of the Forest Service. By keeping the public forests in the public hands our forest policy substitutes the good of the whole people for the profits of the privileged few. With that result none will quarrel except the men who are losing the chance of personal profit at the public expense.”

69

What made Roosevelt so powerful when working to save western ranchlands was that he was speaking from firsthand knowledge. Insofar that landscapes were left to cowboys, places like Texas would be vulcanized into barren zones of burnt grass, as if vast acreage had been shaved by a giant razor. In 1905 Roosevelt had his Public Land Commission issue an alarming report based on data collected by a team of experts. “The general lack of control in the use of public grazing lands has resulted, naturally and inevitably, in overgrazing and the ruin of millions of acres of otherwise valuable grazing territory,” the report said. “Lands useful for grazing are losing their only capacity for productiveness, as, of course, they must when no legal control is exercised.”

70

But as the historian Deanne Stillman noted in

Mustang

, this dire report was ignored by western Congressmen as taste-curdling U.S. federal government babble and “the range got worse.”

71

X

The fall of 1906 was the first occasion when Roosevelt was able to spend much time at Pine Knot that year. The timing of his visit to Virginia was simple: November 1 was the opening of the wild turkey hunting season in Virginia. Arriving on Halloween, Theodore and Edith stayed for the better part of five days at Pine Knot. The woodsy retreat made Roosevelt immediately content. Being in the Blue Ridge Mountains, where the leaves were turning to dazzling fall colors, was sheer joy to the president. He had been consumed with the Cuban revolt, trust-busting, labor disputes, the Panama Canal, Indian matters, and a congressional election, and the

thought of bagging a wild turkey for supper was a great relief from these pressures. The hunt was hosted by his friend Dick McDaniel, and the word around Charlottesville-Keene was that the wild turkeys were plentiful. A few well-intentioned local farmers tried to secretly stock plump turkeys on Roosevelt’s Pine Knot property to make the president’s hunt a guaranteed success. But word leaked out, and the scheme was aborted. Traipsing about the woods at Pine Knot, a local physician showed the president to a fine covey of quail in a clearing. Roosevelt waved him off. “I want,” he said imperiously, “bigger game than that!”

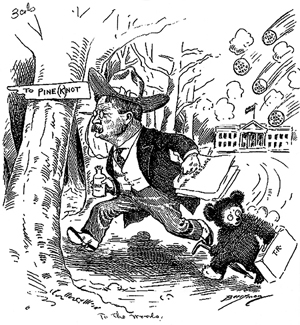

Whenever possible Roosevelt fled the White House to spend time at his rustic cabin, Pine Knot, near Charlottesville-Keene, Virginia.

T.R. races off to Pine Knot.

(Courtesy of the Edith and Theodore Roosevelt Pine Knot Foundation)

On November 4 Roosevelt got his bird. The

Washington Post

and the

New York Times

had articles about the wild turkey’s weight and colors.

72

Never before had Roosevelt eaten a turkey that tasted as fine as this one. Free from the White House’s tedious schedule, he enjoyed the simple nearby things at Pine Knot. Relieved of encumbrances, he wrote enthusiastic letters about the game bird to both his son Kermit and old Bill Sewall in Maine.

73

In 1907, Roosevelt wrote an essay about the wild turkey hunt, “Small Country Neighbors,” for

Scribner’s Magazine

. As a literary effort the piece stylistically recalled “Sou’-Sou’-Southerly,” written twenty-seven years earlier, or something in a publication of the Boone and Crockett Club. “Small Country Neighbors” was a celebration of the American simple life: a turkey hunt, fresh vegetables, a small cabin or hut in the woods, a tent on the shore. Roosevelt wrote: “Each morning I left

the house between three and five o’clock, under a cold, brilliant moon. The frost was heavy; and my horse shuffled over the frozen ruts…. It was interesting and attractive in spite of the cold. In the night we heard the quavering screech owls…. At dawn we listened to the lusty hammering of the big logcocks, or to the curious coughing or croaking sound of a hawk before it left its roost.”

74

The exaltation of hunting wild turkeys—and killing one—in the crisp air got Roosevelt thinking again about the Appalachians. He very much wanted to create an eastern forest reserve in the Blue Ridge Mountains to match the vast western reserves in the Rockies. But this idea was akin to heresy in West Virginia, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia. In 1901, in his First Annual Message, Roosevelt had proposed such an eastern forest reserve to Congress. He wanted it to include vast parts of the Shenandoah Mountains of Virginia, the White Mountains of New Hampshire, and the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee–North Carolina. Congress, however, had refused. By late 1902 Roosevelt had grown extremely frustrated that both Democratic and Republican politicians were hindering his plan for an eastern reserve. He wanted to strangle them. The nonauthoritarian part of being president—i.e., working with Congress—annoyed him no end. With regard to natural resource management before the Antiquities Act, Roosevelt’s authoritarianism was often foiled in the legislative process. “I should like to see the Government purchase and control the proposed great South Appalachian preserve,” he wrote to a friend, “but there are very grave practical difficulties in the way.”

75

From his correspondence during the fall of 1906, it is clear that Roosevelt was deeply worried about the survival of the Blue Ridge Mountains if unregulated timbering persisted. Too many farmers in Virginia were wasting soil, water resources, and forestlands along the James River. Human greed never ceased to amaze Roosevelt. Studying the Round Rock depot outside Charlottesville one afternoon, taking a casual inspection stroll as he’d done as New York’s police commissioner, surrounded by green walls of trees, Roosevelt saw that once-pristine forests were girdled, and chopped-up trunks were piled high in lumberyards along the tracks. How utterly unnecessary and regrettable the scene was. To Roosevelt, cutting trees in the Blue Ridge to make room for the plow was a good thing. But massacring mile upon mile of land just for lumber was criminal, as was companies’ refusal to replant. “American consumption of lumber was greater than ever before,” the historian Roy M. Robbins writes in

Our Landed Heritage

. “It was estimated in 1905, that to supply the Portland

[Oregon] mills alone, 80 acres of timber had to be cut every twenty-four hours.”

76

The situation was just as bad—if not worse—in Virginia.

XI

While Roosevelt was hunting wild turkey in Virginia, the 1906 congressional elections were held. Generally speaking, it was a good day for Republicans (progressive) in the North and Democrats (progressive) in the South. But in what was interpreted by political pundits, in part, as displeasure with Roosevelt’s intense conservationism, twenty-eight Republican seats were lost in the U.S. House of Representatives. This meant that the Republican majority was lessened by fifty-six seats (it was now 222 to 164). One casualty of the election was John F. Lacey of Iowa’s Sixth District. Apparently the voters didn’t care that Lacey was America’s authority on petrified logs in the Arizona desert; they wanted solutions to the economic downturn of 1906 (which would turn into the Panic of 1907). Iowans living in towns like Oskaloosa, Pella, and Eddyville had real problems and spared little thought for Anasazi cliff dwellings, Zuni cave drawings, and the mating habits of little green herons. Congressmen were supposed to bring back pork to the home district not establish federal parks, forests, and bird reservations in other states and territories.

Nothing seized Roosevelt’s attention quite like an electoral debacle. Losing Lacey in Congress, for instance, was a blow, because Lacey had so ably aided the conservationist movement in the congressional Committee on the Public Lands. But Roosevelt realized, stoically, that every politician had his day and Lacey’s had lasted for thirty-seven years. With his congressional career now terminated, Roosevelt inquired whether Lacey wanted a cabinet appointment or an ambassadorship. Lacey’s answer was no. He preferred to practice law in Oskaloosa. What an unsung American hero this Iowan was! Without Lacey, there might have been no model bird laws in Florida, no reintroduction of bison in Oklahoma, and no preservation of cliff dwellings in the Southwest. Mesa Verde might have been destroyed without his intervention. William Hornaday correctly said of Lacey that “he was never elsewhere than on the firing line.” A movement was under way in November 1906 to create a “monument as lofty as his own purposes and as imperishable as his fame.”

77

The accomplishments of Lacey’s governmental career were never forgotten by Roosevelt, who, on returning from Panama, planned to designate as national monuments three southwestern prehistoric sites favored by Lacey.

From Pine Knot the president headed to Norfolk, setting sail for Panama on November 9, 1906, to see “how the ditch is getting along.”

There had been no cases of yellow fever in Panama City since November 11, 1905; the amazing Dr. William Gorgas had eradicated this scourge from the isthmus. So Roosevelt, with a group of military personnel at his side, was ready for an inspection tour. The first days passed peacefully at sea. Much of his correspondence while he was aboard the USS

Louisiana

dealt with Cuba and America’s naval power. Yet he also kept colorful naturalist notes. “All the forenoon we had Cuba on our right and most of the forenoon and part of the afternoon Haiti on our left,” Roosevelt wrote to his son Kermit, “and in each case green, jungly shores and bold mountains—two great, beautiful, venomous tropic islands.” Among meditations on voodoo, cannibalism, Dutch sea dogs, Vasco Nuñez de Balboa, and the Chagres River flood, Roosevelt wrote about the tropics, proud to think that he had saved wild parts of Puerto Rico, Florida, and Louisiana from destruction. “The deluge of rain meant that many of the villages were knee-deep in water, while the flooded rivers tore through the tropic forests,” he wrote of Panama. “It is a real tropic forest, palms and bananas, breadfruit trees, bamboos, lofty ceibas, and gorgeous butterflies and brilliant colored birds fluttering among the orchids. There are beautiful flowers, too. All my old enthusiasm for natural history seemed to revive, and I would have given a good deal to have stayed and tried to collect specimens.”

78

Halfheartedly reporting on the engineering feats associated with the Panama Canal, Roosevelt was proud of his achievement but seemed to prefer being a naturalist. He saw himself as an advance scout for the American Museum of Natural History, which didn’t acquire specimens from Panama until 1914.

79

When the

Louisiana

anchored in Puerto Rico, Roosevelt rushed out to inspect the Luquillo National Forest area he had created in 1902. After reading Biological Survey reports about the rain forest and parrots, he now examined them on his own. Returning to his childhood habit of drawing animals, Roosevelt once again doodled parrots and turtles. “The scenery was beautiful,” he wrote to Kermit. “It was as thoroly [

sic

] tropical as Panama but much more livable. There were palms, tree-ferns, bananas, mangoes, bamboos, and many other trees and multitudes of brilliant flowers. There was one vine called the dream vine with flowers as big as great white water lilies, which close up tight in the daytime and bloom at night. There were vines with masses of brilliant purple and pink flowers, and others with masses of little white flowers, which at night smell deliciously.”

80