The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (109 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Likewise, African-American ministers in New York protested against putting a human being in a cage with a monkey. The Reverend Dr. R. S. MacArthur of Cavalry Baptist Church announced a coordinated “agitation” aimed at freeing Ota Benga. Reports of the whole affair were getting more and more sordid. “It is too bad,” MacArthur said, “that there is not some society like [the New York Society] for the Prevention of the Cruelty to Children.” MacArthur went so far as to say that Benga was a slave. “We send our missionaries to Africa to Christianize the people,” he remarked “and then we bring one here to brutalize him.” He also went directly after Hornaday, saying that “the person responsible for this exhibition degrades himself as much as does the African.”

54

In accordance with the Bronx Zoo’s educational mission, an informational plaque was placed outside Ota Benga’s cage. It read:

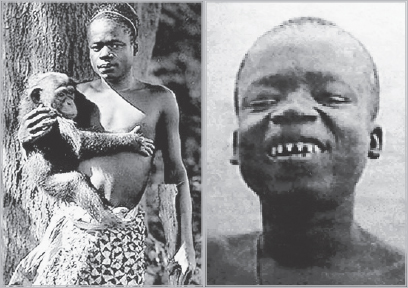

Ota Benga was degraded by being put in a cage as a supposedly Darwinian exhibit at the Bronx Zoo. Benga was often made to pose with monkeys and had his teeth sharpened to look like a cannibal.

Ota Benga.

(Courtesy of the American Museum of Natural History)

The African Pygmy, “Ota Benga.” Age 23 years. Height, 4 feet 11 inches. Weight, 103 pounds. Brought from the Kasai River, Congo Free State, South Central Africa by Dr. Samuel P. Verner. Exhibited each afternoon during September.

That September the tabloids ran stories about Ota Benga—some sympathetic, others mocking. Facts came out: the Bronx Zoo hadn’t purchased the pygmy; he was on loan, so the charge of slavery was a guffaw. The

New York Evening News

condescendingly noted that while Benga was black, he wasn’t coal-black—he wasn’t actually on the bottom rung of the descent of man. That rung was occupied by more dark-skinned blacks. A spirited debate also ensued about whether Benga was a real pygmy or a dwarf or midget. There was great interest also in his sharply filed teeth, which led speculations about cannibalism. Schoolchildren visiting the zoo goaded Benga to rip at raw meat hurled at him by keepers. Benga’s nickname was “Bi,” and kids taunted him with it until he waved at them. One afternoon Benga, refusing to wear strange clothes, broke away from his keeper. When he was eventually apprehended he was brandishing a knife; quickly, the zookeepers disarmed him.

55

“We are taking excellent care of

the little fellow,” Hornaday said in the Bronx Zoo’s defense. “He has one of the best rooms in the primate house.”

56

A few courageous Baptist ministers kept coming to the zoo to protest the incarceration of Ota Benga. Although there is no record of President Roosevelt’s getting involved in the controversy, Hornaday nevertheless started feeling pressure to reverse course. Charges of zoological quackery were starting to arise. “I do not wish to offend my colored brothers’ feelings or the feelings of any one for that matter,” Hornaday said. “I am giving the exhibitions purely as an ethnological exhibit. It is my duty to interest visitors to the park, and what I have done in exhibiting Benga is in pursuance of this. I am a believer in the Darwinian theory.” However, he insisted that Darwinism wasn’t the main reason for displaying the pygmy. Hornaday was a Nebraskan, raised on the frontier, and Ota was his counterpart to Geronimo in the Wild West show. After all, Buffalo Bill had received accolades for parading Apache performers around dusty fairgrounds. Why should Hornaday get pummeled in the press over a Congolese pygmy? Such criticism was selective and hypocritical. Exasperated, and tired of fierce criticism from newspapers and ministers, Hornaday went on to explain that Benga slept in the primate house because it was the most obvious and most “comfortable” place for him to bed down at the zoo.

57

What was Hornaday supposed to do? Have him sleep with the zebras?

On Sunday, September 16, more than 40,000 visitors came to the zoo and went to the monkey house to see Ota Benga. As a special attraction, Bi had been let out of the cage and was free to wander around the zoological park, though with a keeper at his side. “They chased him about the grounds all day, howling, jeering and yelling,” the

New York Times

reported of the spectators. “Some of them poked him in the ribs, others tripped him up, all laughed at him.” Fearing for the pygmy’s life, the keeper put Benga back in his cage. “Me no like America,” Benga said. “Me like St. Louis.”

58

Eventually, unable to shake off the criticism, Hornaday cracked. Arriving at work on Monday, with a pack of newsmen firing questions at him, Hornaday threw in the towel. “Enough!” he said. “Enough! I have had enough of Ota Benga, the African pigmy. Ring up the Brooklyn Howard Colored Orphan Asylum. Tell them that they can get busy tinkering with his intellect. I’m through with him here.”

59

Benga was shunted off to the orphan asylum, supposedly as a free man. But he really wasn’t free. In 1900, Governor Roosevelt had signed into law

an act banning discrimination in public schools; yet, oddly, it wasn’t applicable in orphanages.

60

Dressed in a white suit, Benga was kept as a sort of mascot at Howard. He remained something of a celebrity, and he was taught math and a few hundred English words and was introduced (forcibly it seems) to the New Testament. But because there were children at the asylum, Benga was segregated from the mainstream of the institution. The cooks fed him scraps in the kitchen, away from the children’s view. Because he became a chain-smoker, he was deemed a bad influence on young people. The relocation to the orphan asylum was becoming a failure for all involved, so another Plan B was tried. In 1910 Benga was shunted off to Lynchburg, Virginia, where he worked on a tobacco farm in the Tidewater region. Deeply disturbed by his experience as a zoo exhibit, and longing for his African homeland, Benga committed suicide in 1916: a pistol shot to the heart. When Hornaday heard about the suicide he was very unsympathetic. “Evidently,” Hornaday wrote, “he felt that he would rather die than work for a living.”

61

The small world that is history ridicules Hornaday over the Benga episode. But his views about the University of Man were once taken seriously and given credence throughout America in the early twentieth century. All over the nation, government-run eugenics offices had opened. In 1910, in fact, there was a Eugenics Record Office, created and founded by rich industrialists. An effort was made by the strong to weed out the weak in the “American race.” This misguided movement was an outgrowth of a theory called social Darwinism and is often seen as a step toward Nazism. From 1900 to 1935, thirty-two states adopted laws that allowed sterilization of “defective humans.” Only half-jokingly, H. L. Mencken said that all the southern sharecroppers needed to be sterilized. As Karl W. Gibson points out in

Saving Darwin

, more than 60,000 Americans were sterilized in the early twentieth century because they had epilepsy or stuttered or were mentally challenged. Ota Benga was, in a sense, a victim of the eugenics movement.

62

IX

On September 24, 1906, a few days after Ota Benga was transferred from the Bronx Zoo to Brooklyn Howard Colored Orphan Asylum, Roosevelt at last set aside Devils Tower on two square miles of Wyoming wilderness, as a national monument (A clerical error omitted the apostrophe in Devil’s Tower, and it has never been reinstated.) Once the Antiquities Act passed in June, Frank W. Mondell, representative at-large from Wyo

ming, began pushing for Devils Tower to become the first national monument. Although he was vehemently opposed to national forests, Mondell, a resident of nearby Newcastle, Wyoming, correctly surmised that Devils Tower could, if properly promoted, become a first-rate tourist attraction, bringing tourist dollars to Newcastle, Gillette, and Sundance. Although Devils Tower was out of the way, there was a possibility that tourists visiting the Black Hills would make a day’s outing to see the bear claw marks.

*

63

(Mondell wanted to build an iron stairway from bottom to top: evidently he didn’t think it would be obtrusive, possibly because he had no idea what “obtrusive” meant.) As a member of the House Committee on Public Lands, which Lacey chaired, Mondell worked with the GLO all summer to get the size of the site over 1,000 acres so that the tower could be properly cared for and managed.

Depending on where a visitor was standing and what the angle of sunlight was, Devils Tower produced various impressions. At the top reaches the colors were grays; the bottom had soft reds, pastel rust, and yellow-olive combinations. There were almost no roads to the tower in 1906; travelers coming from the east had to ford the swollen Belle Fourche River seven or eight times. From a distance the Tower seemed, deceptively, to be always within grasp.

A cursory look at the Wyoming newspapers of September 25 shows zero interest in the new federal designation. After all, to locals the site was still just forlorn Devils Tower. Unfortunately, the Roosevelt administration had no ranger to assign to the tower. The commissioner of the GLO, Fred Dennett, did provide a “special agent” based in Laramie, Wyoming, whose job included halting commercial vandalism and homesteading on the new national monument property. On the Fourth of July locals were allowed to attempt climbs to the top. What made national monuments so confusing was that, depending on what was expedient on a case-by-case basis, they were under the jurisdiction of one of three departments: Interior, Agriculture, or War. (Eventually, in 1916, they were all brought into the Department of the Interior.)

64

Because the special agent didn’t live at Devils Tower, locals started chipping off hunks of the rock formation for souvenirs. Eventually “No Trespassing” signs were posted all around Devils Tower as a deterrent; these worked, to a limited degree. However, not until the 1930s, when

roads were built, did Roosevelt’s first national monument finally become a major tourist attraction, with full-time federal protection services provided.

If all Roosevelt had been doing from June to September 1906 was creating Devils Tower National Monument and Mesa Verde National Park, the academic debate over whether he was a

preservationist

or a

conservationist

would not arise. Clearly, his actions on behalf of these western sites, no matter how prosaic the language of the Antiquities Act, made him a thoroughgoing preservationist. Yet throughout the summer of 1906 Roosevelt was also deeply involved with the building of dams, bridges, and reservoirs in the frontier landscape of the West, under the Reclamation Act. Emblematic of the progressive era, his Reclamation Service now had more than 400 engineers and other experts working in Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma. More than 1 million acres of arid land was being irrigated (and this irrigation entailed digging 800 miles of canals, tunnels, and ditches). The Roosevelt administration was giving the American West a concrete and steel reconstruction for the sake of water. This activity by the Reclamation Service caused newspapers in the West to rejoice. Reclaimed land west of the Mississippi River, in fact, could soon sustain 100 million people, owing to wise water policy.

65

“The crowded conditions of the eastern communities will be automatically relieved,” the

Ellensburg

(Washington)

Dawn

predicted, “a happy and contented, home-loving and home-owning people will occupy the present arid regime of the west.”

66

Just as the Panama Canal was a triumph of engineering, so too was the hauling of 16 million cubic yards of American earth under the Reclamation Service’s guidance. Roosevelt had hired more than 10,000 men and 5,000 horses to reclaim the arid west. The days of general surveys and land examinations were over—the time had come for housing communities to be built in places like Los Angeles, Phoenix, Albuquerque, and Oklahoma City. “We may well congratulate ourselves upon the rapid progress already made, and rejoice that the infancy of the work has been safely passed,” Roosevelt wrote to Gifford Pinchot. “But we must not forget that there are dangers and difficulties still ahead, and that only unbroken vigilance, efficiency, integrity, and good sense will suffice to prevent disaster…. There remains the critical question of how best to utilize the reclaimed lands by putting them into the hands of actual cultivators and homemakers, who will return the original outlay in annual installments paid back into the reclamation fund; the question of seeing that the lands are used for homes, and not for purposes of speculation or for the building up of large fortunes.”

67

Because 1906 was a midterm election year, Roosevelt tried to push his conservation policy into the slipstream. He boasted about how smart he was to have Pinchot running the Forest Service out of Agriculture (not Interior). To Roosevelt, Pinchot remained a golden boy who could do no wrong. Roosevelt believed that under Pinchot’s stewardship the U.S. Forest Service was intensely engaged in making sure all western reserves resources contributed mightily to the “permanent prosperity of the people who depend upon them.” Western entrepreneurs lambasted Roosevelt and Pinchot’s forest reserve policies as socialism, but the president believed his administration’s foresight guaranteed future jobs to stockmen, miners, lumbermen, railroad employees, and small ranches. And it was helping to end rural water shortages. If the western forests were destroyed, there would be no water, and cities would become ghost towns.