The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (22 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

To an ornithologist the sheer diversity of the marine environment of Mount Desert Island offered merriment. Seabirds such as jaegers, shearwaters, puffins, and razorbills were everywhere, prancing around in the surf then flying away when the shades of twilight fell under the full onset of the sea. At Thunder Hole, Theodore and Alice sat entranced as seawater waves rushed in and out of a perfectly formed cave while debonair black skimmers circled above. Soon, however, Roosevelt was sick again, this time stricken with cholera morbus. Dehydration, diarrhea, and body flux ensued. There were no pills or port or morphine to make him feel better. Not only was he unable to show off for Alice but, as he wrote to his sister Corinne on July 24, the infectious gastroenteritis was “very embarrassing for a lover…unromantic…suggestive of too much ripe fruit.”

17

Refusing to be an invalid, Roosevelt decided to climb Newport Mountain—with Bar Harbor at its base—as a quick cure while he was recuperating. Onward and upward he went for more than 1,000 feet, peering down at the little harbor skiffs, which looked like bathtub toys from

that crow’s nest vantage point. Given that he was ill, Roosevelt’s mountaineering feat at Newport can be attributed only to sheer will—a will ever growing, ever persistent in overcoming obstacles.

II

There was another reason, however, that Roosevelt didn’t collect birds on Mount Desert Island—his mind was reeling over his coming Midwest hunting trip with his brother, Elliott. Together they were going to explore the broad expanse of the Great Plains. Ever since Dresden, Theodore had been struggling to keep pace with Elliott, the most troubled of the four Roosevelt children. Handsome, irreverent, and charming, Elliott—a tenderhearted bon viant—constantly fought against fatigue, dizzy spells, and bouts of depression. He gave no meaningful signs of professional ambition; he simply excused himself from serious work, preferring pleasure. But he was very sweet-natured. According to a well-circulated family story, Elliott, when he was seven years old, took a walk one winter morning only to return without his overcoat. On being interrogated by his parents Elliott explained that he had seen a homeless “street urchin” shivering, so naturally he gave the poor lad his own coat. “I can think of many occasions in his later life when generosity of the same kind actuated him, not, perhaps, to wise giving, for unlike some people he never could learn to control his heart by his head,” his daughter Eleanor Roosevelt, first lady from 1933 to 1945, recalled. “With him the heart always dominated.”

18

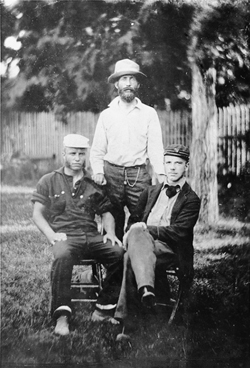

Theodore Roosevelt and his brother, Elliott, with a big game hunting coach.

T.R. and Elliott with big-game hunting coach. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

A better all-around student than Theodore, Elliott (or “Nell” as the family affectionately called him) was also a tremendous hunter and equestrian who excelled at polo.

19

By 1880 Elliott had already hunted wild turkey in Florida and Bengal tigers in India. “Everything is in an advanced state in Texas,” he had written to his father from Fort McKavett, where he was bagging around a dozen birds daily. “By everything I mean all fruits, flowers and vegetables and by Texas I mean the civilized portions thereof.”

20

A crack shot and excellent rider, sly as a magpie, Elliott was not overtly proper like his father; he had unfortunately inherited Uncle Rob’s libertine ways and was attracted to the bottle.

21

Leaving Maine on August 6, Theodore visited Alice at Chestnut Hill and then his family at Oyster Bay. In the middle of the month Elliott and Theodore boarded a Chicago-bound train from Manhattan, ready to roll across the prairies Francis Parkman had written about so dramatically in

The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky Mountain Life

.

22

Like Roosevelt, Parkman believed that actually visiting American landscapes was essential for gaining impressionistic reportorial material to help make a historical narrative come alive for the reader. It electrified Roosevelt that Parkman, a fellow Harvard alumnus (class of 1846), had used his classical education to honor the western frontier in serious historical prose. Roosevelt adopted Parkman—a devoted naturalist and horticulturist, with expertise in roses and lilies—as his guiding light in history studies. And Parkman knew the forests of America better than anybody else alive. To Roosevelt, Parkman, who also suffered from bad eyesight and was nearing blindness, was quite simply “the greatest historian whom the United States had yet produced.”

23

Given a choice between

Walden and The Oregon Trail

, Roosevelt would have chosen the latter every time.

On the weekend before the Roosevelt brothers’ “Midwest tramp,” Theodore was pining for Alice in Chestnut Hill. Although he was quite excited about seeing Chicago and crossing the Mississippi River for the first time, he was already “frightfully homesick” for her. Still, there was a lot of packing and there were many good-byes to make for what was he was calling his western trip. And once they were under way to Chicago, he was filled with excitement, behaving like an able-bodied seaman about to discover the world. “Traveled all day through the wooded hills of Pennsylvania and the rolling prairie of Ohio,” Roosevelt excitedly recorded in his diary. “It is great fun to be off with old Nell; he and I can do about anything together; we never lose our temper under difficulties and always accomplish what we set about.”

24

Chicago in 1880 was the regional hub for the entire Midwest. All the major grain-producing states—Iowa, Illinois, Indiana, and Nebraska—used the city as their in-transit wholesale distribution center. If Roosevelt had looked at a railroad map of the trans-Allegheny West, in fact, he would have seen clearly that Chicago was the crossroads—or like a fist with all the ubiquitous track lines extending outward like fingers. The novelist Theodore Dreiser referred to late-nineteenth-century Chicago as the “magnet” city of the Midwest and West. Pioneers overlanding to California by covered wagon or railroad, or on foot, usually began their journey in Chicago. The city had been built on the bottom lip of Lake Michigan and rebuilt after the great fire of 1871. Freighters carried timber and iron ore south from Wisconsin and Minnesota to the city’s cargo ports, warehouses, and railroad yards. Not only did railroads converge there, but the Illinois and Michigan Canal linked Lake Michigan to the Mississippi River, opening up the agricultural markets of the Midwest. In just four years the first skyscraper—the Home Insurance Building—would be erected on the corner of LaSalle and Adams streets. The city was expanding at an amazing clip.

The eye of Chicago seemed to be looking everywhere across America. As the historian William Cronon pointed out in his landmark study

Nature’s Metropolis

(1991), Chicago in the late nineteenth century oversaw an economic domain that stretched from the Sierra Nevada to the Appalachians, and from Duluth, Minnesota, in the north to Cairo, Illinois, in the south. All the varied ecosystems of the Great Plains about which Roosevelt would later be so enthusiastic—the Sandhills of Nebraska and the Wichita Mountains of Oklahoma, the Great Basin of Nevada and the Badlands of the Dakotas—were all linked to Chicago in one way or another.

25

Given his predilection for the outdoors, Theodore wasn’t elated with Chicago; he itched to leave for the neighboring prairies. Having conquered the Adirondacks, the North Woods, and Mount Desert Island, he craved the fabled pastoral life of the Great Plains, which Washington Irving had written about in

A Tour on the Prairies

(1835).

26

As a fan of Zebulon Pike, he had a headful of frontier myths about discovering the headwaters of the Red and Arkansas rivers (he never quite found them on this Midwest tramp). Over the coming weeks, Theodore and Elliott would hunt grouse, with the euphoria of treasure hunters, in three separate locales: Huntley, Illinois; Carroll, Iowa; and Moorhead, Minnesota, which sat on the border of the Dakota Territories.

The Roosevelt boys’ guide in Illinois was “a man named Wilcox”—his

first name remains unknown—whom Theodore mentions only perfunctorily in the diaries he kept.

*

Clearly, to Theodore’s mind, Wilcox was no Bill Sewall or Moses Sawyer. But in a letter of August 22 to his sister Anna—posted from the Wilcox farm in Illinois—T.R. did reflect on the hardworking midwesterners he was meeting. Huntley was a tiny village with only one paved street. From the town center there was plenty of cropland to be seen in every direction, but there were virtually no woods—only a few scattered trees. “The farm people are pretty rough but I like them very much,” he wrote to Anna. “Like all rural Americans they are intensely independent; and indeed I don’t wonder at their thinking us their equals, for we are dressed about as badly as mortals could be, with our cropped heads, unshaven faces, dirty gray shirts, still dirties [dirtier] yellow trousers and cowhide boots; moreover we can shoot as well as they can (or at least Elliott can) and can stand as much fatigue.”

27

In many respects, the Midwest tramp became a hunting competition. Which brother could bag the most game? Because Elliott, who was two years younger, had already worked up his competitive appetite by flushing out prairie chickens in scrub brush in the Texas, he was the veteran. To Theodore, by contrast, it was all a new experience. He noted in his diary that it was “great fun to try this open plains shooting to which I am entirely unaccustomed among such vast, almost level fields, with so few trees.”

28

After a couple of days in what Theodore referred to as the “fertile grain prairies,”

29

both brothers had bagged many kinds of game birds—doves, ducks, snipes, grouse, plovers. They also collected gophers, impressed by their curved claws, used for tunneling through loose oil. “We had three good days of shooting,” he wrote to Anna, “and I feel twice the man for it already.”

30

Yet ultimately the rural folks he encountered in Huntley fascinated Roosevelt more than the prairie chickens in the brush. Being a hunter and bird-watcher had taught him the art of observation, and now he was applying it to studying both rural and transient people. This would become a trademark of his future hunting and wilderness books. “I have been much amused by the people in this house, especially the labourers; a great, strong, jovial, blundering Irish boy; a quiet, intelligent yankee; a reformed desperado (he’s very silent but when we can get him to talk

his reminiscences are very interesting—and startling); a good natured German boy who is delighted to find we understand and can speak ‘hochdeutch,’” he wrote to his mother on August 25. “There are but two women; a clumsy, giggling, pretty Irish girl, and a hard-featured backwoods woman who sings methodist hymns and swears like a trapper on occasion.”

31

At times on his Midwest tramp it almost seemed that Roosevelt was an onlooker, observing the styles and fashions and habits of American characters with the eye of a novelist. Although never abandoning his aristocratic bearing and always staying a bit removed, Roosevelt sometimes actually wore the garb and adopted the folkways of the regional people he encountered, in hopes of blending in. You might say he was a method actor of the Stella Adler school, playing in an American Arthuriad while mixing it up with different midwestern types like Iowa wheat farmers or Illinois dairymen. Elliott still dressed like a man of substance, sticking to gold scarves and polished boots. His wardrobe expressed his innate sense of aristocratic entitlement, and he had even taken to smoking a long-stemmed pipe. By contrast, Theodore wore dungarees and cotton work shirts and preferred his boots mud-stained. “I am afraid you would disown me if you could see me,” he boasted to his mother from the Illinois prairie. “I am awfully disreputable looking.”

32

The bird collecting in Huntley, however, was a disappointment. “Before the sun was up we started off, tramping in sullen silence through the wet prairie grass,” he wrote in his diary, “but we found few birds and shot very badly.”

33

Truth be told, the flat Illinois countryside lacked the geographical breadth Roosevelt had hoped to encounter. “I broke both of my guns, Elliott dented his, and the shooting was not as good as we expected,” he wrote to his sister Corinne. “I got bitten by a snake and chucked headforemost out of the wagon.”

34

On August 27, after a particularly bad day’s hunting, a dejected Roosevelt recorded, “The country is shot out.”

35

The Roosevelt brothers returned to Chicago for a few days to clean up and plot the next phase of their expedition. They stayed at the Hotel Sherman, which had burned down in the great fire and been rebuilt. Theodore found it off-putting and dreary. If he had wanted society life or afternoon tea, he could have gone to the Fifth Avenue Hotel. Still, he wasn’t much interested in meeting labor activists or radicals of any stripe, either. Nor did he write about the swirl of immigrants—Germans, Irish, Poles, and Swedes—who were pouring into the city. What was exciting to him, however, was Chicago’s role as the gateway to the great West. Walk

ing the railyards he could for the first time imagine Lincoln’s rise as a populist, and the drama of Bleeding Kansas. How strange it was to think that Mary Todd Lincoln was living downstate in corn-stubbled Springfield, where her husband was buried, housebound after being released from the Bellevue Place insane asylum. It had been fifteen years since the tragedy at Ford’s Theatre, but Roosevelt still considered himself a Lincoln man. He could sense the power of Lincoln’s presence everywhere in Illinois and the surrounding prairie—the ghost of Lincoln, as the poet Vachel Lindsay wrote, haunted the streets, and “the sick world” still cried.

36