The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (31 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

All of Roosevelt’s major outdoors adventures between 1880 and 1884 were vividly recounted in

Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

(subtitled

Sketches of Sport on the Northern Cattle Plains

). Putting his college education to good use, he wrote about Minnesota grouse, Montana buffalo, Dakota Territory bighorn sheep, Great Plains antelope, and Bighorns bears. Chronology was abandoned, often to the reader’s confusion, in favor of biological and topographical edification. Showcasing his erudition as a naturalist was Roosevelt’s first priority; recounting thrilling hunts was a close second. Most chapter titles, in fact, had to do with wildlife: “Water Fowl,” “The Grouse of the Northern Cattle Plains,” “The Deer of the River-Bottoms,” “The Black-Tail Deer.” Roosevelt wrote that the American West was a Darwinian laboratory full of amazing wildlife action. “The doctrine seems merciless, and so it is; but it is just and rational for all that,” Roosevelt wrote about

On the Origin of Species

. “It does not do to be merciful to a few, at the cost of justice to the many.”

21

The villains of

Hunting Trips

were the “swinish game butchers” who ruthlessly hunted for hides “not for sport or actual food,” and who cold-bloodedly murdered the “gravid doe and the spotted fawn with as little hesitation as they would kill a buck of ten points.”

22

Whenever T.R. turned polemical on behalf of good sportmanship, he echoed the ethical sentiments and concerns of his uncle Robert B. Roosevelt and the

sporting press, such as

Forest and Stream

. Like Uncle Rob pontificating on the essential beauty of shad, trout, and eels, throughout

Hunting Trips

Roosevelt gave loving naturalist observations about the elk, antelope, and buffalo he had hunted. Not all, however, was blood and thunder. There was an “Indian guide” feel to much of the prose. For example, Roosevelt wrote quietly about stumbling upon a white-tailed deer’s resting spot with the “blades of grass still slowly rising, after the hasty departure of the weight that has flattened them down.”

23

Reading

Hunting Trips

makes it abundantly clear that Roosevelt deeply respected these deer.

Although cherry-picking is required, genuine conservationist beliefs can be excavated from the pages of

Hunting Trips

. For example, true western outdoorsmen, Roosevelt wrote, would have to become citizen-protectors of the wildlife being devastated by bands of destructive rogues. In almost every chapter he feared the day when elk, buffalo, and prairie chickens would vanish forever. “No one who is not himself a sportsman and lover of nature can realize the intense indignation with which a true hunter sees these butchers at their brutal work of slaughtering the game, in season and out,” he wrote in

Hunting Trips

, “for the sake of the few dollars they are too lazy to earn in any other and more honest way.”

24

By expressing such views in 1885, Roosevelt was pitting himself against the railroad behemoths, telegraph companies, real estate brokers, and even Buffalo Bill, whom he respected as a master horse-breaker.

25

Although there are only a few such passages—in a book that promoted the joys of big game hunting—

Hunting Trips

nevertheless marked the beginning of Roosevelt’s great crusade for the conservation of deer, elk, antelope, big-horn sheep, and bears. Wringing a livelihood from the “outdoors” literary marketplace instead of U.S. naval history now became an all-important occupational pursuit for Roosevelt to juggle along with politics, ranching, and managing the family trust. And in wildlife protection he had found his cause.

Hunting Trips

received impressive reviews that July. The

New York Times

, for example, said that the book was clear-eyed and would seize “a leading position in the literature of the American sportsman.” Although the first part of the review focused on Roosevelt’s ethnological delineation of cowboy culture, the

Times

also noted that his naturalist writing on the survivalist tactics of white-tailed deer was exemplary. “The common deer, or whitetailed deer, found in almost any State in the Union, he tells us was not so plentiful five years ago on the northern plains as it is to-day,” the unidentified reviewer wrote. “With this deer its increase seems

to be due to its particular habits. It seeks the densest coverts, is fond of wet and swampy places, and is rarely jumped by accident. It demonstrates the survival of the fittest.”

26

Overnight

Hunting Trips

became the seminal study of both the Badlands and the Bighorns. The core message Roosevelt conveyed was that hunting big game was good for the American soul. Bouts of barbarism, Roosevelt believed, reawakened the primitive and the savage in a man, to good effect. It was a theme that pervaded his writings for the rest of his life. “In hunting, the finding and killing of the game is after all but a part of the whole,” he later wrote. “The free, self-reliant, adventurous life, with its rugged and stalwart democracy; the wild surroundings, the grand beauty of the scenery, the chance to study the ways and habits of the woodland creatures—all these unite to give to the career of the wilderness hunter its peculiar charm. The chase is among the best of all national pastimes; it cultivates that vigorous manliness for the lack of which in a nation, as in an individual, the possession of no other qualities can possibly atone.”

27

II

One mixed review, however, caught Roosevelt’s attention amid the cavalcade of raves.

28

The thirty-five-year-old naturalist George Bird Grinnell, the esteemed editor of

Forest and Stream

, did compare

Hunting Trips

to Francis Parkman’s

The California and Oregon Trail

and Lewis H. Garrard’s

Wahtoyah and the Taos Trail

because of its “freshness, spontaneity, and enthusiasm” on the other hand, Grinnell criticized Roosevelt for generalizing too much about the western species he had encountered while hunting, for failing to discuss color variations properly, and for other inaccuracies of zoological detail. The slightly patronizing review observed that although the youthful Roosevelt had studied a particular antelope herd in Montana, the herds in Manitoba or Saskatchewan were not necessarily identical to it. Grinnell believed that Roosevelt was talented, but that to be a real Darwinian zoologist he should have spent more time doing field observations before rushing into print with his first impressions, which were sometimes inaccurate despite being well written. “Mr. Roosevelt is not well known as a sportsman, and his experience of the Western country is quite limited, but this very fact in one way lends an added charm to this book,” Grinnell wrote, damning Roosevelt with faint praise. “He has not become accustomed to all the various sights and sounds of the plains and the mountains, and for him all the difference which exists between the East and the West are still sharply defined….

We are sorry to see that a number of hunting myths are given as fact, but it was after all scarcely to be expected that with the author’s limited experience he could sift the wheat from the chaff and distinguish the true from the false.”

29

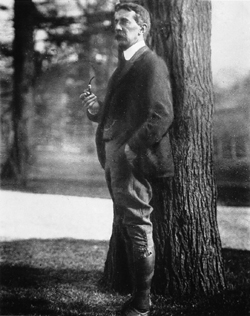

George Bird Grinnell was the editor of

Forest and Stream

and a co-founder of the Boone and Crockett Club with Theodore Roosevelt. The

New York Times

deemed him the “father of conservation.”

George Bird Grinnell. (

Courtesy of John F. Reiger

)

The review stung Roosevelt, who prided himself on the scientific exactitude of his animal descriptions. Grinnell, it seemed, had taken Roosevelt down a notch. Doubly frustrating was the fact that Grinnell had championed Roosevelt’s conservation activism in

Forest and Stream

the previous year, praising his efforts in the New York state assembly to halt the damming of streams that fed the Hudson River. “It is satisfying to see,” Grinnell had written, “now and then, in our legislative halls, a man whom neither money, nor influences, nor politics can induce to turn from what he believes to be right to what he knows to be wrong.”

30

But now, in 1885, Grinnell had become Roosevelt’s enemy.

After reading the review, Roosevelt stormed into the offices of

Forest and Stream

demanding a meeting. Always cordial, Grinnell agreed, and they sat together for hours going through

Hunting Trips

almost page by page. To Roosevelt’s surprise, the erudite editor seemed to know more about bighorn sheep and white-tailed deer than he did. Once Roosevelt’s bruised ego was salved, the conversation turned to conservation issues, specifically big game protection. “I told him something about game destruction in Montana for the hides, which, so far as small game was con

cerned, had begun in the West only a few years before that,” Grinnell recalled; “though the slaughter of the buffalo for their skins had been going on their extermination had been substantially completed. Straggling buffalo were occasionally killed for some years after this, but much longer and by this time…the last of the big herds had disappeared.”

31

By the time Roosevelt left the headquarters of

Forest and Stream

no lingering animosity or grudge would spoil his new friendship with George Bird Grinnell, who fast became as close a friend as Henry Cabot Lodge. When it came to saving wildlife the two men were in sync. And Roosevelt had learned a lesson: never again would he leave himself vulnerable to charges of faking about nature or of mischaracterizing species. Instead of being rivals, Roosevelt and Grinnell united in what would become a lifelong crusade to save the big game animals of the American West from extinction.

32

“Roosevelt called often at my office to discuss the broad country that we both loved, and we came to know each other extremely well,” Grinnell recalled decades later. “Though chiefly interested in big game and its hunting, and telling interestingly of events that had occurred on his own hunting trips, Roosevelt enjoyed hearing of the birds, the small mammals, the Indians, and the incidents of travel of early expeditions on which I had gone. He was always fond of natural history, having begun, as so many boys have done, with birds; but as he saw more and more of outdoor life his interest in the subject broadened and later it became a passion with him.”

33

It was easy to see why Roosevelt was captivated by Grinnell, who was nine years his senior. Grinnell, a native of Brooklyn, was an explorer, rancher, hunter, bird-watcher, ethnologist, published author, first-rate editor, and western folklorist. (And as if that weren’t enough, the

New York Times

would later call him the “father of American conservation.”

34

) Like the Roosevelts, the Grinnells had deep roots in the United States, having arrived in Rhode Island as far back as 1630.

35

A real sophisticate, always impeccably dressed, with a pipe close at hand, he knew more about the American West, and more about North America’s 650 mammal species, than any other scholar alive. Puff-puff-puffing, he would discuss why kit foxes were the pygmies of the fox group and why the spotted skunk had the strongest scent of the species.

When Grinnell was seven, his family had moved to Audubon Park in upper Manhattan, the thirty-acre estate that had served as the great ornithologist’s last home. The hallways there were cluttered with overhanging elk and deer antlers, “which supported guns, shot pouches, powder flasks, and belts.”

36

The grounds were full of wild animals for Audubon to

study and draw. The walls of Audubon Park, in fact, groaned with paintings and hunting trophies once belonging to the great Audubon.

37

A close friendship developed between the young Grinnell and Audubon’s widow, Madame Lucy. The old barn was filled with ornithologists’ collections of skins and specimens, and Grinnell absorbed Audubon’s influence. The nearby Hudson River became his bird-watching laboratory. “In winter the river was often very full of ice, and eagles and crows were constantly seen walking about on the ice, no doubt feeding on refuse and the bodies of animals thrown into the stream north,” Grinnell wrote in a partially unpublished memoir. “The crows used to roost on a cedar-covered knoll north of the Harlem River in what is now the Bronx, not very far from Highbridge, and each morning they flew low among the tree tops.”

38

As an undergraduate at Yale, Grinnell had the same problems in the classroom that Roosevelt would have at Harvard. He was too enamored with the idea of following in the footsteps of his idol to sit still in the classroom. Grinnell’s life mission crystallized when he read Audubon’s 1843 account of traversing the Missouri and Yellowstone rivers. A passage Audubon wrote in his journal, a lament about the buffalo slaughter on the Great Plains, was seared into Grinnell’s mind and became, in a sense, a mission statement. “What a terrible destruction of life,” Audubon wrote, “as it were for nothing…as the tongues only were brought in, and the flesh of these fine animals was left to beasts and birds of prey, or to rot on the spots where they fell. The prairies are literally

covered

with the skulls of the victims.”

39