The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (32 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Then Audubon had fired off a verbal challenge that would launch the modern conservation movement. “This cannot last,” Audubon said of the buffalo slaughter. “Even now there is a perceptible difference in the size of the herds, and before many years the Buffalo, like the Great Auk, will have disappeared; surely this should not be permitted.”

40

Those last six words—“surely this should not be permitted”—galvanized Grinnell. With the encouragement of Professor Othniel C. Marsh (no relation to George Perkins Marsh), the leading paleontologist in the United States, Grinnell volunteered to work on a Yale-sponsored Great Plains dinosaur dig in 1870, writing that he was “bound for a West that was then really wild and wooly.”

41

Grinnell had read every one of Mayne Reid’s books as a boy, so the American West beckoned to him like the star of Bethlehem. While collecting fossils at Antelope Station in Nebraska, Grinnell encountered buckskin scouts, drifters, gold-seekers, Christian farmers, itinerant preachers, and Plains Indians. It was just the first of many trips west, during which he

befriended such legendary figures as Charley Reynolds, Buffalo Bill, and Frank and Luther North. By the time he reviewed Roosevelt’s

Hunting Trips

in July 1885, he not only had been part of the Marsh Paleontological Expedition but had made scientific discoveries in support of Darwinism, had accompanied Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer to the Black Hills in 1874 when gold was discovered, and had joined Captain William Ludlow of the Army Corps of Engineers the next year in surveying Yellowstone.

42

And nobody alive wrote about duck hunting with more authority than Grinnell.

43

Believing that Native Americans had been “shamefully robbed” by the U.S. government, Grinnell worked side by side with Plains tribes,

44

inspiring enough trust and confidence that many of the Indian bands gave him a special name: to the Pawnee, he was “White Wolf,” an honorary member of the tribe; to the Cheyenne he was

wikis

(“migratory bird”); to the Blackfeet he was “Fisher Hat,” in recognition of his ability to find fish in seemingly depleted streams; and to the Gros Ventres he was “Gray Clothes,” because of the dull suit he often wore.

45

By 1885 he was known as

the

American expert on the ethnology of the Plains Indians. The anthropologist Margaret Mead saluted Grinnell’s pioneering efforts on behalf of saving Indian tribal culture as recently as 1960, using the word “classic”

46

to describe his book about the Cheyenne.

47

(The great western writer Mari Sandoz did the same in 1962.

48

)

So when Roosevelt stormed into Grinnell’s office at

Forest and Stream

he was dealing with a heavyweight. Starting in 1882, using the magazine as a soapbox, the editor began crusading to save natural resources. Among other environmental causes he promoted seasonal licenses, laws against killing young animals, the need to preserve habitat, and the need for game wardens. Grinnell was small in stature, with large ears, and usually sported a well-trimmed mustache or goatee; his regal personality stood in sharp contrast to that of the bombastic Roosevelt. Grinnell was also soft-spoken, self-effacing, and humble—yet there was nothing timid about his approach. When he spoke about the American West, people listened. He believed strongly that scientists should get mud on their boots, and he dreamed of forest reserves, bison parks, restocked rivers, and greenbelts around western cities. To the scientific-minded Grinnell, there was an interconnectedness to nature. Even if the United States had the best game laws in the world, they meant nothing without forest protection. Last but not least, Grinnell encouraged states to create zoological societies—a lobbying campaign at which he proved successful in New York.

As a self-appointed watchdog for Yellowstone National Park, Grinnell constantly denounced overcommercialization and federal mismanage

ment. After witnessing hunters slaughter elk and deer in the park in 1875, he had written a scolding letter promoting big game conservation there and included it in the Ludlow Expedition report. Over the years to come, with a great deal of success, Grinnell would lobby the U.S. Senate to preserve the territorial integrity of Yellowstone. “My account of big-game destruction [in Yellowstone] much impressed Roosevelt, and gave him his first direct and detailed information about this slaughter of elk, deer, antelope, and mountain-sheep,” Grinnell recalled. “No doubt it had some influence in making him the ardent game protector that he later became, just as my own experiences had started me along the same road.”

49

Early in 1886, a few months after the publication of

Hunting Trips

, Grinnell helped form the Audubon Society to protect birds from extinction. From the get-go he had no stronger ally in those efforts than Theodore Roosevelt. As the historian John Reiger observed in 1972 in

The Passing of the Great West

, “Grinnell, the originator and amalgamator of ideas,

prepared

Roosevelt for Gifford Pinchot, the President’s famous environmental administrator.”

50

It was the alliance of Roosevelt and Grinnell (not Roosevelt and Pinchot) that launched the modern conservation movement in earnest. To Roosevelt, Grinnell was an American treasure whose likeness should have been cast in granite.

III

By late August 1885, following the publication of

Hunting Trips

, Roosevelt was back in the Badlands. The Elkhorn Ranch was now completely built, with eight rooms, a large stone fireplace, numerous windows, and a center hall—all adorned with taxidermy. Buffalo robes, deer antlers, and bearskins were strewn about the place. There were so many mule deer sheds and elk sheds on the piazza that it looked like an antler museum. Roosevelt converted the cellar into a photography darkroom; taking pictures of nature was yet another of his hobbies. There were two stables, together often housing as many as thirty horses. Roosevelt entertained and wrote at the Elkhorn (most of the real ranching work, however, was done from the Maltese Cross),

51

and especially enjoyed sitting on the porch facing the piazza-like area in front of the ranch house. “Just in front of the ranch veranda is a line of old cottonwoods that shade it during the fierce heats of summer, rendering it always cool and pleasant,” Roosevelt wrote. “But a few feet beyond these trees comes the cut-off bank of the river through whose broad sandy bed in the shallow stream winds as if lost except when a freshet fills it from brim to brim with foaming yellow water.”

52

The big news around Medora was that Marquis de Mores had been

arrested for murdering Riley Luffsey, a buffalo hunter who loathed de Mores’s barbed wire. De Mores was now in jail in Bismarck, awaiting trial. Furthermore, there was a rumor that he was furious at Roosevelt over land boundaries, cattle prices, Roosevelt’s rude ranchhands, and much else. Because Roosevelt was essentially a squatter, in the last years before fences and deeds transformed the open range into fixed property, enforcing boundaries was constantly a cause of friction. Sharp letters were exchanged between the two rich cattlemen. Talk of a pistol duel was even bandied about, but it proved empty. Eventually de Mores was found not guilty of murdering Luffsey.

53

In any event, his arrest had been, at worst, an unpleasant distraction to Roosevelt, who had founded the Little Missouri Stockmen’s Association and prided himself on his western leadership role even more than on being a New York assemblyman. And the stockmen’s association did more than settle land and brand issues. Because of a drought, brushfires were common in the Badlands that summer. As head of the association, Roosevelt worked side by side with his neighbors to put out the blazes, many started by Plains Indians angry at white settlement.

By September 16 Roosevelt was headed back east, stopping at the Bismarck jail for a brief visit with de Mores. In the spring, writing

Hunting Trips

had left Roosevelt physically depleted, but now he was in high spirits back home in New York. He attended the state Republican convention in Saratoga Springs and spent time with his little Alice. Friends were impressed by his general happiness and vitality. For the first time since his wife’s death, he was open to the idea of a new romance. This changed attitude allowed him to reconnect with his childhood sweetheart, Edith Carow. “For nineteen months (since the deaths of Alice and Mittie) they had successfully avoided each other,” Sylvia Jukes Morris wrote in

Edith Kermit Roosevelt

. “But sometime early that fall, either by chance or design, they met.”

54

Deeply refined, quietly attractive, and unmarried, Edith Carow was then twenty-four and still infatuated with Theodore. As Roosevelt had been winning elections and writing critically acclaimed books, his sister Bamie had constantly updated Edith, with whom she’d remained friends. Victorian etiquette called for a long mourning period, so as Theodore and Edith grew closer, they were very discreet. Even after Edith accepted Roosevelt’s proposal that November, they behaved in public only as friends for a full year. Somehow three years “in waiting” seemed much more socially appropriate than only two.

That Christmas season Roosevelt circulated at numerous social gath

erings with Edith at his side. Nevertheless, he didn’t use her full name in his diary, referring to her as only “E” and reserving all his affection in the journal for Alice. No love letters between the two survive—Edith ordered their correspondence destroyed—and, in fact, it’s quite possible there weren’t any. By all accounts, Edith was an intensely private woman, with a unique ability of tamping down Roosevelt’s over-the-top enthusiasms. “Edith was not the sort of person to encourage rhapsodies anyway,” according to the historian Edmund Morris. “She disapproved of excess, whether it be in language, behavior, clothes, food, or drink.”

55

Keeping Sagamore Hill running and maintaining the Dakota ranches were expensive propositions for Roosevelt. As marriage plans were privately discussed, he dreamed of having a large family. Keeping bloodlines alive mattered to him a great deal. Although he could live comfortably on his trust fund, he needed book advances to feel financially secure. At Henry Cabot Lodge’s suggestion Roosevelt signed a contract with Houghton Mifflin to write a biography of Thomas Hart Benton, the senator from Missouri who from 1821 to 1851 had fervently encouraged westward expansion.

56

It would be part of a new series called American Statesmen. During January and February 1886 Roosevelt started writing

Thomas Hart Benton

in earnest, taking advantage of New York’s fine research libraries. Edith’s company was welcome, too, but still he kept thinking about the Badlands. A conscientious businessman, he knew, always checked up on his investment. Imagining Sewall and Dow suffering in the cold, worried that his dogies and yearlings wouldn’t make it through the winter, he returned to Medora at the end of the winter planning to write

Benton

there while collecting new material for a sequel to

Hunting Trips

. “I got out here all right, and was met at the station by my men,” he wrote to Bamie on March 20 from the Elkhorn. “I was really heartily glad to see the great, stalwart, bearded fellows again, and they were honestly pleased to see me. Joe Ferris is married, and his wife made me most comfortable the night I spent in town. Next morning snow covered the ground; but we pushed to this ranch, which we reached long after sunset, the full moon flooding the landscape with light. There has been an ice gorge right in front of the house, the swelling mass of broken fragments having been pushed almost up to our doorstep…. No horse could by any chance get across; we men have a boat, and even then it is most laborious carrying it out to the water; we work like Arctic explorers.”

57

Four days later thieves stole Roosevelt’s boat (an unusual object in the semiarid Badlands) by using a knife to cut the towline tied to the piazza. As chairman of the Little Missouri Stockmen’s Association of Dakota-

Montana, Roosevelt had been given the position of deputy sheriff of what is today Billings County.

*

He felt it was his duty to catch the scoundrels, so once he calmed down he hatched a plan. They would construct another scow and then light out after the thieves. (You could almost hear the wheels turning: what a good article or essay the catching of the crooks would make in

Century

magazine.) So the new boat was built, and off they went in hot pursuit, like Pat Garrett. Disconcertingly, Roosevelt, always bent on self-improvement, brought along copies of Leo Tolstoy’s

Anna Karenina

and Matthew Arnold’s collected poetry with him so as not to be bored.

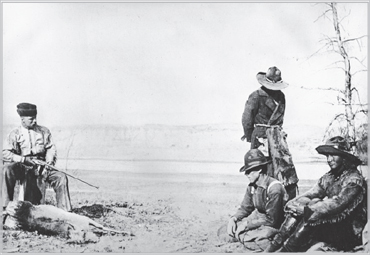

Theodore Roosevelt guarding the thieves who stole his boat. The staged photo was taken in September 1884

.

T.R. guarding the boat thieves. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

For a few days Roosevelt—with the help of a wagon driver—tracked the thieves in this new boat, sleuthing for clues along the riverbank. Occasionally he found fortuitous footprints as clear as if sealed in wax. Most of his daytime hours, however, were spent navigating around ice floes. For supper he killed deer and rabbits. After pursuing his prey more than eighty miles he captured the three thieves (Burnsted, Pfannenbach, and Finnegan) at Cherry Creek in McKenzie County. By the time he marched back to Dickinson, all six men had blistered feet and frostbitten toes.

Typically Roosevelt boasted that the man-hunt was a “bully affair” (and he got his whopping good story to write about for

Century

). If he felt exhausted he moaned in silence. He even finished

Anna Karenina

along the way for good measure. Typically vainglorious, Roosevelt later had reenactment photographs taken of himself, his rifle keeping his three weary prisoners at bay. Nevertheless everybody in Dickinson was abuzz about their daring new deputy sheriff. “He was all teeth and eyes,” the town doctor, Victor Stickney, wrote of first encountering T.R. “His clothes were in rags from forcing his way through the rosebushes that covered the river bottoms.”

58