The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (36 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

That Christmas season was a joyous one for Roosevelt. When

Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail

*

was published in December, most reviewers applauded his well-crafted prose and Frederic Remington’s fine engravings and pen-and-ink line drawings. Whether T.R. was writing about cattle branding at Elkhorn, cowboys’ rope tricks, or goat hunting in the canyon of the Coeur d’Alene, Remington delivered spot-on illustrations that electrified the narrative. Although

Hunting Trips of a Ranchman

had been a better book than

Ranch Life and the Hunting-Trail

, Remington’s sketches upgraded the latter into an enduring western classic. Nobody alive could draw mountain men, French-Canadian trappers, or timber wolves with the realistic precision of Remington. (For some reason, however, Remington could never properly depict mountain lions, a deficit that annoyed Roosevelt.)

Like Remington, Roosevelt had romantic sentiments about the American West, finding it an almost inexhaustible source of material for books and articles. “Civilization seems as remote as if we were living in an age long past,” Roosevelt wrote approvingly about being a westerner in

Ranch Life

. “Ranching is an occupation like those of vigorous, primitive pastoral peoples, having little in common with the humdrum, workaday business world of the nineteenth century; and the free ranchman in his manner of life shows more kinship to an Arab sheik than to a sleek city merchant or tradesman.”

35

Remington wanted merely to draw the reality in

Ranch Life

. “I don’t consider that there is any place in the world that offers the subjects that

the West offers,” he once observed. “Everything in the West is life, and you want life in art…. The field to me is almost inexhaustible.”

36

By contrast, Roosevelt was on an accelerated mission to save its wilderness areas and big game. Underneath his name on the title page of

Ranch Life

, Roosevelt identified himself as president of the Boone and Crockett Club of New York: the club had become a “bully pulpit” for his ideas about wildlife management and forestry reserves. In the text, he mourned for the “fast vanishing” elk and told readers that when hunting deer they should shoot “only the bucks.”

37

The descriptions in

Ranch Life

of shifting weather and natural wonders were both precise and poetic. Roosevelt’s zoological descriptions rose to the high standard Grinnell had inspired at

Forest and Stream

. Of antelope, for instance, he wrote: “Antelope see much better than deer, their great bulging eyes, placed at the roots of the horns, being as strong as twin telescopes. Extreme care must be taken not to let them catch a glimpse of the intruder, for it is then hopeless to attempt approaching them. On the other hand, there is never the least difficulty about seeing them.”

38

Predictably, Roosevelt ended

Ranch Life

with a boast about the natural grandeur of the American West. With jingoistic but good-natured pride he tried to one-up both Asia and his brother, Elliott. (The fact that he had turned thirty didn’t mean the sibling rivalry had dissipated.) Elliott, at this juncture, however, was on an alcoholic downslope, desperately struggling with depression and contemplating suicide. “My brother has done a good deal of ibex, mountain sheep, and markhoor shooting in Cashmere and Thibet [Tibet], and I suppose the sport to be had among the tremendous mountain masses of the Himalayas must stand above all other kinds of hill shooting,” Theodore wrote. “Yet, after all, it is hard to believe that it can yield much more pleasure than that felt by the American hunter when he follows the lordly elk and the grizzly among the timbered slopes of the Rockies, or the big-horn and the white-fleeced, jet-horned antelope-goat over their towering and barren peaks.”

39

Unfortunately, T.R. didn’t get to bask in the acclaim that

Ranch Life

received. That winter, to meet his publisher’s deadline, he was working overtime on

The Winning of the West

. Puffy-eyed, he burned the midnight oil nightly until three or four in the morning. Somewhat naively, he had promised G.P. Putnam’s Sons the first two volumes by the spring of 1889. Always tottering toward a physical breakdown, pushing himself beyond the usual human limits, whenever possible Roosevelt locked himself up at Sagamore Hill and wrote. His entire nervous system was strained. Desperately he tried blocking out both good and bad news. With two children

to raise, Edith constantly worried that bills had to be paid. (She made sure all financial obligations were met.) Whenever the issue of financial insolvency was raised, however, Roosevelt’s blue eyes would darken in disapproval. His exuberance would be temporarily extinguished. Life for Theodore had become a pressure cooker of deadlines, commitments, responsibilities, and financial insecurity. Only the finances, however, made him irritable. His great consolation was that at least he hadn’t become a leech, or one of those fellows who always looked for other people to carry the load.

V

Although Roosevelt doesn’t mention it in

An Autobiography

, there may have been another impetus for creating the Boone and Crockett Club in 1887. The previous year, anxious to professionalize mammalogy, Dr. C. Hart Merriam of the Department of Agriculture elevated the Economic Ornithology section at the Department of Agriculture into the Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy.

40

In principle, the new division was intended to help farmers cope with pests. But in practice, Dr. Merriam was interested in the distribution of mammals across the United States. Owing to the creation of the Audubon Society and the American Ornithologists Union, birds were starting to be properly studied. Two exhaustive “bulletins,” in fact, were published in the late 1880s: W. W. Cooke’s “Bird Migration in the Mississippi Valley” and Walter B. Barrows’s “The English Sparrow in America.”

41

But nobody was publishing similar high-quality bulletins about chipmunks, skunks, squirrels, gophers, ferrets, groundhogs, or dozens of other American mammals.

Merriam—short in stature, with a mustache that made him look like an otter—soon changed that. Merriam’s agriculture division began conducting general surveys of mammals (as well as birds), with a keen eye toward biotic community distributions. Using field reports and scientific results, he constructed life-zone maps. For the first time in American history a biological understanding of cougars’, wolves’, or bears’

ranges

became available to the general public. Nobody had ever inventoried American wildlife quite like Merriam. A crucial component of his success was his uncanny ability to reach out to untrained, backyard naturalists and mammal collectors throughout America. In any given state or territory there was bound to be a local hunter who had preserved the skins of such diurnal species as rabbits and squirrels. “It was from such sources that many of his specimens came and he carried on a large correspondence,” the naturalist historian Wilfred H. Osgood recalled of Merriam in

the

Journal of Mammalogy

, “promoting interest in mammals by purchasing specimens and, in some cases, by employing collectors or at least by placing standing orders.”

42

A truly practical biologist, Merriam also pioneered in using a new trap for small mammals: called the Cyclone, it was made of tin and wire springs, had an area of only about two square inches when collapsed, and was easily portable in quantity. Merriam sent Cyclones to Roosevelt with the idea that when he was in the Rockies he could set up such traps around cabins and creeks, then carefully perform taxidermy on the little mammals and ship the specimens back to Washington, D.C. (Although this is speculative, Merriam may have sent these traps because he was jealous—since Roosevelt had sent the Idaho water shrew to Baird, Merriam’s friendly competitor in collecting.)

Although Merriam’s shop was officially the Division of Economic Ornithology and Mammalogy, Roosevelt called it the Bureau of Biological Survey (which is what it officially became on March 3, 1905, the day Roosevelt was inaugurated as president in his own right). The Geological Survey mapped the topography of America after the Civil War, and Roosevelt envisioned the Biological Survey doing the same for the classifications of plants, birds, and animals. The Biological Survey, with Merriam at the helm, proved that temperature extremes were partially responsible for how wildlife was distributed. Although only about five or six crackerjack naturalists were ever on his official payroll, Merriam established a grassroots network of specimen collectors from all over America, a particularly notable achievement in an era when there were no telephones, let alone the Internet. He published a pathbreaking study of the San Francisco Mountain Region and Desert of the Little Colorado, Arizona establishing from summit to base six life zones in the flora of the mountains: Lower Sonoran (Sonoran Desert plants); Upper Sonoran (Colorado pinyon and juniper woods); Transition (Ponderosa pine forest); Canadian (Rocky Mountain Douglas fir and white fir forest); Hudsonian (tree line forests of Rocky Mountain bristlecone pine and Engelmann spruce); and Arctic-Alpine (alpine tundra).

*

A founder of the National Geographic Society, Merriam joined the American-British fur seal commission determined to save the great herds

of Alaska from extinction, in the same way that Roosevelt and Grinnell were protecting the buffalo. By the time Merriam became president of the Biological Society of the Cosmos Club in Washington, D.C. in 1891, he was considered the greatest authority on applying Darwinian theory to American species and topography.

43

Writing reports from Arizona and saving seals constituted the fun part of Merriam’s job at the Biological Survey. As an administrator he had to find ways for wildlife and humans to coexist in America. Everything from poisoning ground squirrels with barley and strychnine to promoting lime and sulfur wash to prevent rabbits from attacking orchards fell under his job description. Anxious to save the beaver from being over-hunted, Merriam became a supersalesman on behalf of muskrat fur as an alternative. Starting in 1886 he also oversaw publication of the

Annual Reports of the Biological Survey

. He also made sure U.S. Department of Agriculture “bulletins” were printed and disseminated all over the country.

44

If you were a farmer in Mississippi or Arkansas, for example, constantly shooting raccoons as varmints, Merriam was the national voice that would say, “Not a good idea.” Raccoons fed on crayfish, which infested leveled embankments; so the raccoons were actually providing a pest-control service by destroying the potentially destructive crustaceans. Such pragmatic solutions to wildlife control are why Roosevelt respected Merriam so much. When it came to wildlife protection, Merriam was a living instruction manual.

L

AYING THE

G

ROUNDWORK WITH

J

OHN

B

URROUGHS AND

B

ENJAMIN

H

ARRISON

I

I

t is strange now to picture them meeting for the first time in March 1889 at the Fellowcraft Club at 32 West Twenty-Eighth Street in New York. With a membership of around 200 sophisticated newspapermen, writers, and artists, the Fellowcraft had the kind of leather-chair ambience preferred by the literary-minded aristocrats of the gilded age. The thirty-year-old Theodore Roosevelt was one of the club’s younger members. Although he was preparing to move to Washington, D.C., for his new post as U.S. civil service commissioner, he nevertheless continued fulminating against the deplorable conditions in New York City’s notorious cordon of louse-infected tenement slums. No job could ever rein in his multifarious reformist interests and instincts. But Roosevelt dropped his anti-poverty crusade and his history writing on March 7 for a long-coveted opportunity to meet the naturalist John Burroughs. The date, in fact, should be noted in the annals of U.S. conservation history as the cementing of an extremely significant alliance that would last for nearly three decades. “I thought him very vigorous, alive all over, with a great variety of interests; and it was surprising how well he knew the birds and animals,” Burroughs recalled. “He’s a rare combination of the sportsman and the naturalist.”

1

Roosevelt and Burroughs’s lunch reportedly came about through an intermediary. As an assemblyman, Roosevelt had gotten to know Jacob A. Riis, a Danish-born newspaperman whose

How the Other Half Lives

would soon awake the nation to the suffering of New York City’s immigrants. Roosevelt regularly visited a boys’ club run by the reformer and polemicist John Jay Chapman in Hell’s Kitchen with Riis, and would often give away copies of Burroughs’s compilations of essays, such as

Wake-Robin

and

Winter Sunshine

. Chapman, who was a neighbor of Burroughs, arranged to have the two birders meet for lunch at the Fellowcraft Club.

2

Joining them was Elizabeth Custer, the widow of Lieutenant Colonel George Armstrong Custer. Since her husband died at the battle of Little Bighorn

in 1876, she’d published two western memoirs:

“Boots and Saddles” or Life in Dakota with General Custer

(1885) and

Tenting on the Plains or General Custer in Kansas and Texas

(1887). She, too, would have plenty to converse about with Roosevelt.

3

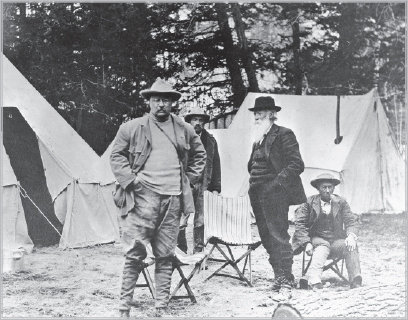

Theodore Roosevelt with John Burroughs in Yellowstone National Park in 1903. The photograph was taken by

Illustrated Sporting News.

T.R. and John Burroughs at Yellowstone camp. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

T.R. was always trying to engulf people up in the tidal wave of his erudition, which some interpreted as monomaniacal self-regard. As one close friend kindly put it, “He was the prism through which the light of day took on more colors than could be seen in anybody else’s company.”

4

But Burroughs was a household name—his books were mandatory reading in schoolhouses all over America—and he made Roosevelt feel inferior.

5

Burroughs didn’t just tramp around the wooded countryside keeping field notes or hunting game—he

was

the wooded countryside personified. Unlike Roosevelt, who was constantly showing off his credentials as a naturalist, Burroughs, as if half divine, believed there was sanctity in every fallen leaf or grain of sand. (Or, as Charles Dickens wrote of a favorite character in his 1854 novel

Hard Times

, he was a “man who was the Bully of humility.” 6

Concerned over the post–Civil War abandonment of agrarian communities in favor of overcrowded cities, the usually benevolent Burroughs

wrote stingingly against “scientific barbarism,” even calling humming factories “the devil’s laboratory.”

7

Raised in the Catskill mountains, Burroughs would rub his eyes in disbelief as he surveyed the environmental degradation of New York City’s waterways. Although Burroughs never postulated a social philosophy per se, there was a sympathy for the Transcendentalists in everything he did or said. But he nevertheless admired captains of industry like Henry Ford and Thomas Edison who rose from the tinker’s bench to change the world. Roosevelt, by contrast, never fully condemned industrialization—he wanted only to break up trusts and to create great American parks, forest reserves, and bird rookeries to help invigorate city dwellers and uplift their urban spirits from chronic factory smoke and industrial disease.

There were other differences between the two naturalists. Burroughs was contemplative whereas Roosevelt preferred direct action, always ready to rumble. Although both men hunted, Burroughs’s pockets didn’t always bulge with bullets. While in

Wake-Robin

Burroughs wrote about a deer hunt in the Adirondacks and about shooting rabbits for sport, his literary talent was better suited to promoting the joy of watching wildlife. The older Burroughs got, in fact, the more hunting bored him. To Burroughs, for example, the American Museum of Natural History was a morgue, an abominable mockery of the great web of vibrant life in the animal kingdom. “A bird shot and stuffed and botanized is no bird at all,” he later told a group of children who came to visit the museum. “And a bird described by another in cold paint is something less than you deserve. Do not go to museums but find Nature. Do not rely on schoolbooks. Have your mothers and fathers take you to the park or the seashore. Watch the sparrows circle over you, hear the gulls screech, follow the squirrel to his nest in the hollow of an old oak. Nature is nothing at all when it is twice removed. It is only real when you reach out and touch it with your hands.”

8

One can be reasonably sure Roosevelt knew Burroughs’s biography from Catskills childhood to

Signs and Seasons

publication practically by heart at the time of their first meeting. Born in Roxbury, New York, on April 3, 1837, Burroughs was six years younger than Theodore Roosevelt, Sr. In his memoir

My Boyhood

, Burroughs wrote of growing up poor on his family’s farm yet being enchanted by juniper trees, gurgling streams, apple orchards, and picturesque dairy farms. “I deem it good luck, too, that my birth fell in April, a month in which so many other things find it good to begin life,” Burroughs wrote in

My Boyhood

. “Father probably tapped the sugar bush about this time or a little earlier; the blue-bird and the robin and song sparrow may have arrived that very day.”

9

While he was growing up, Burroughs’s life revolved around the Roxbury harvest cycle. Enthralled by the cool sweep of the Catskills, he adopted the upstate woodlands as his own “open-air panorama.”

10

By the time he was nine or ten years old, birds—of all kinds—became Burroughs’s fixation. One spring day, he later recalled, a cloud of passenger pigeons descended on a grove of beeches. The birds’ collective noise in his pasture sounded like a gust at sea or a tornado.

11

Not long afterward—while visiting the U.S. Military Academy at West Point—Burroughs, who had started to style himself as a backwoods ornithologist, dipped into a copy of Audubon’s

Birds of America

in the library and couldn’t put it down.

12

The beauty of Audubon’s flamingos and wild ganders was beyond stimulating. (Years later, in 1902, while Theodore Roosevelt was president, Burroughs wrote a biography of Audubon. Its purpose was to restore Audubon’s place as the premier American literary naturalist by virtue of his voluminous journals.

13

) Yet Burroughs noticed that Audubon had also written a ghastly essay on how farmers were slaughtering passenger pigeons by setting tree traps and filling water pots with sulfur. How much more beautiful was the cooing of live passenger pigeons than the heaps of dead birds local farmers used to feed hogs!

To earn a living, Burroughs decided to be a rural schoolmaster. He worked first in New Jersey, not far from the Atlantic coast. When he was twenty years old he traveled to Chicago and had his daguerreotype taken; it shows a rare handsomeness. His longish hair was slicked back, and his straightforward gaze suggested deep wisdom. But Burroughs was always most comfortable in rural settings. Whenever he found himself in New York or Chicago, he would clutch his wallet, worried that pickpockets might spot him as an easy mark. Struggling to find steady work, Burroughs moved to Washington, D.C., in 1862, during the height of the Civil War, and clerked in the Currency Bureau of the Treasury Department. Before long he was befriended by the poet Walt Whitman, who was also living in Washington.

It’s unclear whether Whitman fell in love with Burroughs’s physical beauty or with his rural innocence (or both) in the fall of 1863, but he did fall in love. (There is, however, no evidence of a sexual encounter between them.) To Whitman, his twenty-six-year-old protégé was like an only son; also, Burroughs was an open-hearted romantic with an unjaded face like “a field of wheat.” Mentoring young men like Burroughs came easily to Whitman. He had come to Washington to help nurse the 70,000 Union and Confederate soldiers wounded in action and recuperating in poorly run, unsanitary hospitals. Under Whitman’s tutelage, Burroughs

started writing about nature in a more intimate way, perfecting his literary craft as a prose stylist when he was not working at his desk in the Treasury Department. There was a refreshing hominess to Burroughs’s essays about bullfrogs, maple syrup, and trout spawning. As Burroughs explained, his privileged education under Whitman—who was meticulously working on his cycle of war poems

Drum Taps

when they met—led him to try to “liberate the birds from the scientists.” Unlike Roosevelt, Burroughs wasn’t overly interested in John James Audubon, the hunter and taxidermist extraordinaire, carting around arsenic paste and a shotgun. But Burroughs

did

want to become a writer about green spaces who would be celebrated as the “Audubon of prose.”

14

For the most part Burroughs spent 1863 to 1873 in Washington, D.C., writing outdoors prose. His friendship with Whitman grew and grew; the gray-bearded poet calling the Catskills writer his own personal “naturalist-in-residence” who felt empathy even for quick-breeding insects. To Burroughs, Whitman’s controversial

Leaves of Grass

was “an utterance from Nature, and opposite to modern literature, which is an utterance from Art.”

15

When Abraham Lincoln was shot, Whitman—who used to

cher confrère

with Lincoln whenever they passed on the street—mourned like a grieving widow. The great Lincoln, Whitman moaned, had been stolen away in his prime.

16

Just before the assassination, Burroughs had hiked up Batavia Mountain in the Catskills seeking an afternoon of solitude. Pausing for a moment to catch his breath, he was suddenly mesmerized by the long, ethereal, flutelike song of a hermit thrush. The sounds of this bird held Burroughs transfixed, as if in a dream, for ten or fifteen minutes. Craning his neck high and low, looking up in tree branches and along the ground where the songster might have been foraging, Burroughs struck out. There would be no sighting of a hermit thrush that afternoon. All he took away was a comforting memory of the delicate ringing melody. Upon hearing Burroughs talk effusively about the hermit thrush, Whitman wrote his celebrated eulogy to Lincoln, “When Lilacs Last in the Dooryard Bloom’d.” One verse went as follows:

Solitary the thrush,

The hermit withdrawn to himself, avoiding the settlements,

Sings by himself a song.

Song of the bleeding throat.

17

While Whitman worked on

Leaves of Grass

, Burroughs became his cheerleader, comparing him to Thoreau and Emerson. Encouraged by

Whitman, confident that

Leaves of Grass

was

the

great American masterpiece, the very embodiment of democracy in verse, Burroughs wrote his own first book,

Notes on Walt Whitman as Poet and Person

.

18

Whitman himself helped edit the manuscript, rearranging quotations and sentences. Walks through Washington’s parks now became commonplace for the two nature lovers, who often strolled through the White House gardens or Rock Creek Park in search of a veery thrush or ruby-crowned kinglet.

19

And Whitman was the one who chose

Wake-Robin

—the trillium found in American woods—as a title for Burroughs’s second book. “He thinks natural history, to be true to life, must be inspired, as well as poetry,” Burroughs wrote of Whitman, following one of their hikes. “The true poet and true scientist are close akin. They go forth into nature like friends…. The interests of the two in nature are widely different, yet in no true sense are they hostile.”

20

Whitman’s belief in the special connection between science and poetry was shared by Roosevelt.

As an ice-breaker at the Fellowcraft lunch, Roosevelt had told Burroughs about his European honeymoon with Edith and how Burroughs’s nature books—especially

Birds and Poets

and

Locusts and Wild Honey

—made him long terribly for the United States. Roosevelt added that Burroughs’s prose was “thoroughly American.” Their talk shifted to the reform work Roosevelt was doing to help impoverished New York City boys; Roosevelt told Burroughs that, like Santa Claus, he regularly handed out mint copies of

Wake-Robin

as gifts, instructing the recipients to read every page carefully, for it embodied “all that was good and important in life.”

21