The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (66 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

Roosevelt, apparently sensing that Hitchcock was only three-quarters on board, never fully trusted this cabinet officer. Concerned that pro-development senators from Wyoming and South Dakota wouldn’t like the conservationist-cowboy Bullock being given carte blanche in the Black Hills, President Roosevelt disseminated Bullock’s letter to every legislator on Capitol Hill. No consultation was going on; Roosevelt was informing the legislators that the legendary lawman Bullock was in charge of South Dakota’s rimland management. Hitchcock, contemplating resignation, decided instead to buckle up and join Roosevelt’s progressive cru

sade, even if it meant absorbing all the president’s doomsday histrionics. Balding, with a huge gray mustache, Hitchcock acted around Roosevelt and Pinchot like a wise butler tolerating abhorrent behavior from youngsters because he had no other choice. What Bullock tried to communicate to Hitchcock was that the Black Hills could survive only if timber and water were conserved. “If both are destroyed,” Bullock warned, “the richest 100 miles square will become a desert.”

14

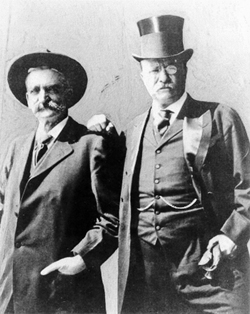

Seth Bullock and Teddy Roosevelt. This photo was taken early in the twentieth century. Roosevelt first met Bullock on a cattle range in 1884, and they became very good friends. Soon after assuming the presidency, Roosevelt appointed Bullock U.S. marshal for South Dakota and Black Hills forest ranger. Bullock had an open invitation to stay overnight at the White House whenever he pleased.

T.R. with Seth Bullock.

(Courtesy of David Dary)

Having the vital Bullock—a forerunner of Shane—on his side was a great relief to Roosevelt. Everybody needs a few bad-weather friends. “I hope to see you in Washington this winter,” Roosevelt wrote to Bullock on September 24. “I want to have you at dinner at the White House, and we will talk over past events. I have been peculiarly pleased to have a man of your type to execute the forest laws, for I know you will see to it that they are enforced absolutely without regard to anything but the law itself. Above all I hope you will see that any Government official who is guilty of laxity or inefficiency is held to a strict account.”

15

What President Roosevelt was trying to accomplish by circulating his correspondence with Seth Bullock to congressional offices was to demonstrate the kind of top-drawer fellow needed to protect the western re

serves. Roosevelt’s vision of law enforcement was hundreds of Bullocks reined up like an Interior Department cavalry on parade, ready to protect the forestlands as a backup for the U.S. Army. Since 1872 Bullock had been perhaps the most vociferous promoter of Yellowstone living in the West. After all, it had been Bullock, as a renegade member of the territorial legislature, who introduced the bill to preserve northwest Wyoming as a “great national park.” Nobody in the West loathed poachers—and arrested them—with the earnest fervor of Bullock. As sheriff in Deadwood, Bullock—who entered the pop culture kingdom in 2004 as the leading character in the HBO television series

Deadwood

—relished protecting the Black Hills from rogue mining outfits operating without proper claims and from rank outlaws illegally prospecting for gold on federal land. And he expressed a sweeping damnation of all lawbreakers. A veteran of Grisby’s Cowboy Regiment in the Spanish-American War and a fierce ally of the Rooseveltian conservation movement, Bullock wanted the upside-down county around Deadwood—specially Devils Tower toward the west and Wind Cave to the east—preserved as national parks.

President Roosevelt modeled his administration’s conservation policy after his own governorship in New York—where he had tried to whittle down the Fish, Game, and Forest Commission to one nonpolitical appointee. Thus a new era in forest conservation and wildlife management policy was under way. As governor of New York from 1899 to 1900 Roosevelt had led an effort to measure every stream and brook in the state. He now wanted to apply that idea nationally.

16

With an air of reasonableness, he warned Secretary Hitchcock that at all costs

nobody

should be employed in Interior solely for political reasons. Instead, Roosevelt wanted “good plainsmen and mountain men, able to walk and ride and lie out at night, as any first-class men must be able to do.” He wanted wilderness warriors who understood forest reserves to lead to overall social betterment in America. His exhibits A and B were Warford and Bullock: outdoorsmen without an ounce of haughtiness or of susceptibility to greed. Remembering how Yellowstone had been hampered by a lack of law enforcement before the protection act of 1894, Roosevelt basically wanted the western territories of Arizona, New Mexico, Indian, and Oklahoma protected by Rough Riders. “In other words,” Roosevelt instructed Secretary Hitchcock, “they are to be rangers in fact and not in name, and no excuse will be tolerated for inability to perform the vigorous bodily work of the position any more than lack of courage and honesty would be excused.”

17

II

President Roosevelt, now living in the White House, became extremely controversial on a number of fronts besides recruiting rangers and running roughshod over Interior in the late fall of 1901. Roosevelt couldn’t help showing his thornier side and his streak of independence, scoffing at both the GOP party line and concerns over states’ rights. Roosevelt had planned to head to Alabama that fall to meet with the “negro leader” Booker T. Washington at Tuskegee Institute. However, suddenly thrust into the presidency, Roosevelt had to cancel this trip. “I write you at once to say that to my deep regret my visit south must now be given up,” Roosevelt informed Washington. “When are you coming North? I must see you as soon as possible. I want to talk over the question of possible appointments in the South exactly on the lines of our last conversation together. I hope that my visit to Tuskegee is merely deferred for a short season.”

18

Everything about Booker T. Washington impressed Roosevelt. Born a slave in Virginia, too poor to attend school, the self-taught Washington nevertheless founded, in 1881, the Tuskegee Institute, a technical school for African-Americans. A believer in Washington’s “accommodationist” view toward whites, Roosevelt declared Washington “the most useful, as well as the most distinguished, member of his race in the world.” In office only a month, Roosevelt invited Washington to the White House as a courtesy on October 4 to discuss a federal judgeship in Alabama. A productive dialogue on race relations ensued; the two leaders stood four-square on many important national issues. Washington was invited back to the White House in mid-October to brainstorm about ways to enhance educational possibilities for African-Americans in the South. Eventually, Washington and Roosevelt, enjoying each other’s breathless enthusiasm, broke for dinner. Joining them were the first lady, Edith Roosevelt (she hadn’t gotten used to being called that), and a professional friend, Philip B. Stewart of Colorado, cougar hunting fame. Everybody had a most enjoyable time.

Holy hell broke out in the South the next day, however, when an AP wire story simply stated that Roosevelt had dined with Washington in the White House. The ground rumbled and the southern press went berserk. A segregationist code had been shattered. Headlines like “Our Coon-Flavored President” and “Roosevelt Dines a Darkie” appeared throughout the former Confederacy. The

New Orleans Statesman

grumbled that the meal was “little less than a studied insult to the South.”

19

The

Memphis

Scimitar

ran an editorial stating, “It is only very recently that President Roosevelt boasted that his mother was a Southern woman, and that he is half Southern by reason of fact. But inviting a nigger to his table he pays his mother small duty. No Southern woman with a proper self-respect would now accept an invitation to the White House, nor would President Roosevelt be welcomed today in Southern homes. He has not inflamed the anger of the Southern people; he has excited their disgust.”

20

Theodore Roosevelt and Booker T. Washington became great friends. Besides inviting Washington to dine at the White House in 1901, Roosevelt also visited Tuskegee Institute in 1904.

T.R. with Booker T. Washington.

(Courtesy of the Theodore Roosevelt Association)

Southern segregationists ripped into Roosevelt with a fusillade of cruel, bigoted, ugly language. James K. Vardaman—publisher of the

Greenwood Commonwealth

, who was a veteran of the Spanish-American War and a Mississippi Democrat and would become governor and then a U.S. senator—surmised that the “White House was so saturated with the odor of the nigger that the rats have taken refuge in the stable.” Roosevelt became nauseated by these insults—such hatred in America was cancerous. The southerners, Roosevelt lamented, had indicted him for trying to encourage literacy and help fight poverty among African-Americans. The

Richmond

(Virginia)

Times

was aghast at Roosevelt’s tolerating the idea that “negroes shall mingle freely with whites in the social circle—that white women may receive attentions from negro men.”

21

Never one to cower in the face of threats, Roosevelt decided to go hunting in Mississippi sometime in 1902—to go into the belly of the beast, almost as an act

of defiance. Not for a split second was he going to let ex-Confederates—of all people—assault his character. In coming months he would continue consulting with his friend Booker T. Washington; only he back-pedaled away from dinners in favor of meetings at ten o’clock in the morning. Roosevelt, however,

did

live up to his pledge to tour Tuskegee, though not until after the 1904 presidential election when being photographed with a “negro” wouldn’t cost him votes.

22

On December 3, Roosevelt was to deliver his First Annual Message to Congress, so he surveyed various friends (including Chapman, Grinnell, and Merriam) about what he might say regarding conservation and wildlife protection. A key to President Roosevelt’s vision of the American West was a vast increase in forest reserves and western irrigation. These tenets would be a fundamental part of his annual message. At the time of McKinley’s death in September 1901 the number of U.S. forest reserves had increased from twenty-eight to forty: a total of more than 50 million acres. Not bad. Building on that adequate legacy, President Roosevelt strategized about how to triple McKinley’s effort. He succeeded in increasing the number of national forests from forty to 159, with a total of more than 150 million new acres.

23

Put another way, the U.S. forest reserves went from about 43 million acres in 1901 to 194 million acres in 1909 under Roosevelt’s leadership. As the historian John Allen Gable computed in the

Theodore Roosevelt Association Journal

, Roosevelt’s new forestlands constituted an area larger than France, Belgium, and the Netherlands combined.

24

Forest reserves aside, President Roosevelt looked back in bafflement over why McKinley had rejected stringent wildlife protection laws. Didn’t McKinley want elk and antelope to populate the Great Plains? Was he really opposed to a moose reserve for Maine? The fact of the matter was that McKinley simply hadn’t wanted to squander political capital with powerful western senators over what he considered fringe issues, such as protecting ungulates. That indifference immediately changed with Roosevelt in power. From the get-go Pinchot, in fact, at Roosevelt’s behest, had brought into the forefront of U.S. conservation policy initiatives which the Boone and Crockett Club had formulated: mainly, having game reserves

inside

national forests. Anxious for his administration to make these bold leaps toward wildlife protection, Roosevelt asked Gifford Pinchot to push the ideas about game reserves through Congress. It didn’t prove easy going for Pinchot. Western development interests didn’t give a damn about buffalo, deer, and elk. Working with the Boone and Crockett Club and the New York Zoological Society, Roosevelt, with

the essential help of Congressman Lacey, nevertheless soon made historic strides in getting wildlife protection legislation.

Deciding unilaterally to change the name of the Executive Mansion to the White House that October, Roosevelt asked Pinchot to head the Division of Forestry in Interior. He promised him “an absolutely free hand”—free, that is, from the gaze of Ethan Allen Hitchcock. Roosevelt claimed his White House desperately needed Pinchot’s help on selecting ideal sites for forest preserves and on intelligent habitat management (including selective timber thinning and brush control). As a lure or incentive Roosevelt told Pinchot that his recommendations for forestry would become—in essence—the de facto administration policy. Pinchot, not Hitchcock, would be the ultimate arbiter at Interior. And while ostensibly Pinchot was merely head of a division, in reality he would have more power than Secretary Hitchcock or the GLO commissioner, Binger Hermann (a former Republican congressman who was an attorney in Oregon). Hitchcock would be a useful figurehead—and an ally of sorts—kept only to placate the McKinley’s old guard. As for Hermann, he smelled to Roosevelt like an enemy, an Oregonian more interested in pork for river and harbor appropriations than in protecting places like Crater Lake, Three Arch Rocks, or the Cascades. Point-blank reality was that Pinchot (as division head) would be making federal forestry policy.

25

(Later, in 1905, Pinchot would become the first chief of the new forestry service).