The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America (135 page)

Read The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America Online

Authors: Douglas Brinkley

At ten o’clock on Inauguration morning, Roosevelt and Taft headed to the Capitol in a twelve-team carriage. Snow was swirling about, and many of the bleachers lining Pennsylvania Avenue were empty owing to the inclement weather. Both men usually had a hearty sense of humor, but it wasn’t on display that day, although T.R. waved to the shivering spectators. Nellie Taft broke all precedent by riding in a carriage with

her husband.

75

At the Capitol, Roosevelt signed some last-minute bills, hugged some close friends, and prepared to relinquish power. Vice President James S. Sherman of New York had already been sworn in. Just after noon, Roosevelt and Taft walked into the Senate Chamber, receiving enormous foot-stomping cheers. For a few minutes they looked like a united front. Then a century-old Bible was held out and Taft took the oath.

76

“Observers were struck by Roosevelt’s immobile concentration as his successor was sworn in,” the historian Edmund Morris wrote in

Theodore Rex

. “Those who did not know him thought that the stony expression and balled-up fists signaled trouble ahead for Taft.”

77

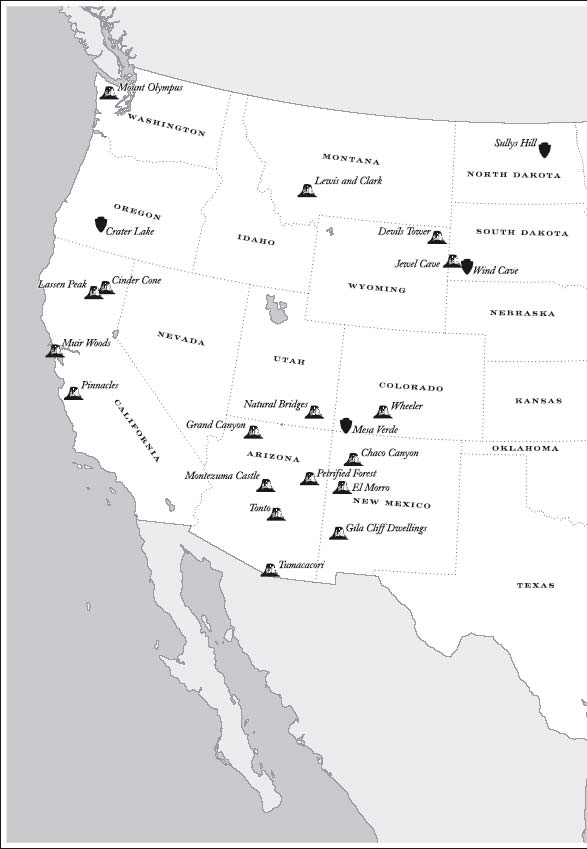

Not since Lincoln had America had such a folk figure as Roosevelt for its president. He was beloved. Groups from all over America wanted to memorialize Roosevelt, chisel his face in granite, or cast a bronze of his likeness. But such gestures were hardly commensurate with his accomplishments, such as saving the Tongass and Mount Olympus. “For millions of contemporary Americans, he was already memorialized in the eighteen national monuments and five national parks he had created by executive order, or cajoled out of Congress,” Morris maintained. “The ‘inventory,’ as Gifford Pinchot would say, included protected pinnacles, a crater lake, a rain forest and a petrified forest, a wind cave and a jewel cave, cliff dwellings, a cinder cone and skyscraper of hardened magma, sequoia stands, glacier meadows, and the grandest of all canyons.”

78

In seven years and sixty-nine days, Roosevelt had saved more than 234 million acres of American wilderness. History still hasn’t caught up with the long-term magnitude of his achievement.

All of Roosevelt’s cabinet dutifully came to see him off at Union Station, but he lingered longest with Pinchot.

79

In coming years Pinchot would become governor of Pennsylvania, forestry advisor to F.D.R., and the co-author of Darwinian travel odyssey from New York to Key West and on to the Galapagos. Pinchot would have the huge burden of keeping the conservation movement kinetic while Roosevelt was in British East Africa. Soft-spoken, almost tearful, Roosevelt was attentive and considerate to everybody at Union Station: children carrying teddy bears; army troops; porters; bystanders; and congressmen with whom he no longer had to negotiate. Already, scholars were trying to determine precisely where Roosevelt would fit in the spectrum of American presidential history. Roosevelt himself believed that he was a smart hybrid of both Jeffersonian and Hamiltonian impulses with modern Darwinism added for good measure. “I have no use for the Hamiltonian who is aristocratic or for the Jeffersonian who is a demagogue,” Roosevelt wrote to William

Allen White shortly before leaving office. “Let us trust the people as Jefferson did, but not flatter them; and let us try to have our administration as effective as Hamilton taught us to have it. Lincoln, and Washington, struck the right average.”

80

At three-twenty that afternoon, Roosevelt left for Oyster Bay as the youngest ex-president in American history. There was about T.R. an air of moral satisfaction. Like Washington and Lincoln, he had accomplished much. He was still walking singular among America’s political class. Regarding conservation alone he had left two watchdogs strategically behind to mind the store. The first was Gifford Pinchot, who would be a gadfly every time Taft failed to protect a Roosevelt natural wonder or forest reserve. And, devilishly, Roosevelt had left a big game trophy at the White House: the head of a huge bull-moose, shot in Maine, still adorned a wall in the executive dining room. For weeks that bull-moose would loom over every presidential meal or conference, until eventually it was taken down. Both the bull moose and Gifford Pinchot were harbingers of difficult days ahead for William Howard Taft. The reign of Theodore Roosevelt hadn’t really ended on that snowy March afternoon. The conservation movement had spread all over America, and his acolytes had just begun to fight for the inheritance of unmarred public lands.

There was no going gently into retirement for Roosevelt. He remained America’s hubristic flywheel and nationalistic sage. British East Africa. Egypt. Rome and Berlin. Paris and London and Oxford. Brazil. Chile. Uruguay. Argentina. The Grand Canyon and the Federal Bird Reservations of the Gulf of Mexico. He visited them all. He dined with European princes and prayed in the Hopi kivas of northern Arizona. And every single day, like an unbroken stream, he crusaded for conservation to prevail over the global disease of hyper-industrialization. “We regard Attic temples and Roman triumphal arches and Gothic cathedrals as of priceless value,” Roosevelt decreed, full of wilderness warrior fury. “But we are, as a whole, still in that low state of civilization where we do not understand that it is also vandalism wantonly to destroy or to permit the destruction of what is beautiful in nature, whether it be a cliff, a forest, or a species of mammal or bird. Here in the United States we turn our rivers and streams into sewers and dumping-grounds, we pollute the air, we destroy forests, and exterminate fishes, birds, and mammals—not to speak of vulgarizing charming landscapes with hideous advertisements.”

81

Freed of the restraints of public office, Roosevelt amped up his recriminations against despoilers, finding solace in the world’s deepest dark forests. Swollen with courage, he created the Bull Moose Party in 1912, in

part to defend his Alaskan forest reserves from exploitation. Even as his sunlight dimmed, he held firm to his visionary stances on wildlife protection and sustainable land management. He saw the planet as one single biological organism pulsing with life and championed the interconnectedness of nature as his own Sermon on the Mount. As forces of globalization run amok, Roosevelt’s stout resoluteness to protect our environment is a strong reminder of our national wilderness heritage, as well as an increasingly urgent call to arms.

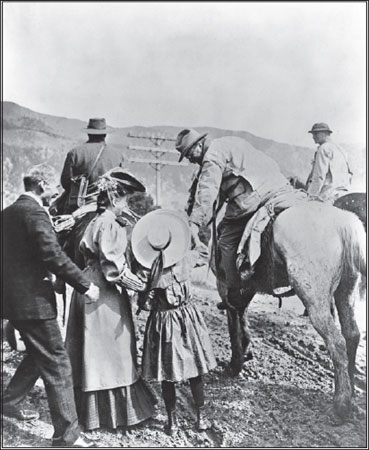

Roosevelt’s greatest White House accomplishment was encouraging young people to join the wildlife and forestry protection movements. Here, the cowboy conservationist reaches out to a Colorado girl

.

T.R. inspired children to join the conservation movement. (

Courtesy of Theodore Roosevelt Collection, Harvard College Library

)

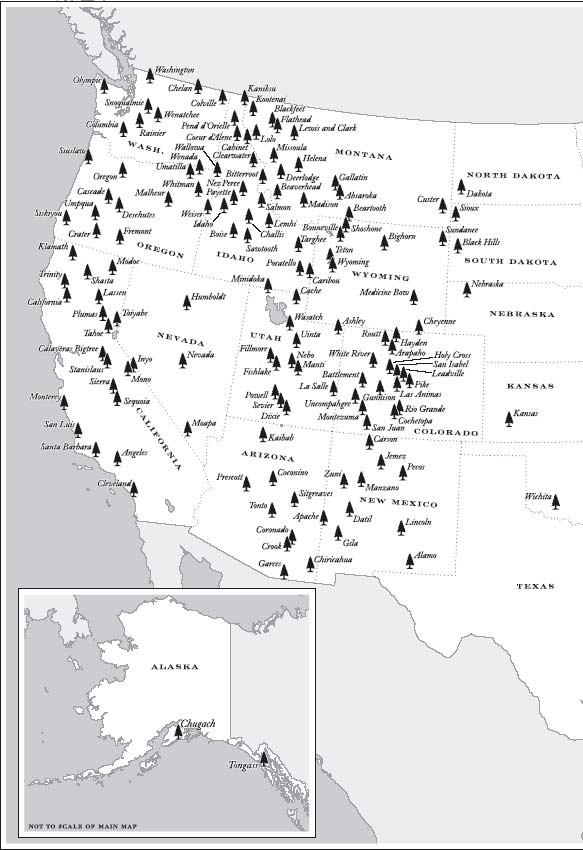

This list was compiled from the

Establishment and Modification of National Forest Boundaries: A Chronological Record

(1891–1973); the annual reports of the Division of Forestry (1886–1901); Bureau of Forestry (1902–1903); U.S. Geological Survey’s

Annual Reports

(1897–1900); and my own additions.

N

ATIONAL

F

ORESTS

C

REATED OR

E

NLARGED BY

T

HEODORE

R

OOSEVELT

, 1901–1909

1. Luquillo (Puerto Rico), renamed El Yunque | January 17, 1903 |

2. White River (Colorado) | May 21, 1904 |

3. Sevier (Utah) | January 17, 1906 |

4. Wichita (Oklahoma) | May 29, 1906 |

5. Lolo (Montana) | November 6, 1906 |

6. Caribou (Idaho and Wyoming) | January 15, 1907 |

7. Colville (Washington) | March 1, 1907 |

8. Las Animas (Colorado and New Mexico) | March 1, 1907 |

9. Wenada (Oregon and Washington) | March 1, 1907 |

10. Olympic (Washington) | March 2, 1907 |

11. Manti (Utah) | April 25, 1907 |

12. Manzano (New Mexico) | April 16, 1908 |

13. Kansas (Kansas) | May 15, 1908 |

14. Minnesota (Minnesota) | May 23, 1908 |

15. Pocatello (Idaho and Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

16. Cache (Idaho and Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

17. Whitman (Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

18. Malheur (Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

19. Umatilla (Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

20. Columbia (Washington) | July 1, 1908 |

21. Rainier (Washington) | July 1, 1908 |

22. Washington (Washington) | July 1, 1908 |

23. Chelan (Washington) | July 1, 1908 |

24. Snoqualmie (Washington) | July 1, 1908 |

25. Wenatchee (Washington) | July 1, 1908 |

26. Fillmore (Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

27. Nebo (Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

28. Lewis and Clark (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

29. Blackfeet (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

30. Flathead (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

31. Kootenai (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

32. Routt (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

33. Cabinet (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

34. Hayden (Colorado and Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

35. Challis (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

36. Salmon (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

37. Clearwater (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

38. Coeur d’Alene (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

39. Pend d’Orielle (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

40. Kaniksu (Idaho and Washington) | July 1, 1908 |

41. Angeles (California) | July 1, 1908 |

42. San Luis (California) | July 1, 1908 |

43. Jemez (New Mexico) | July 1, 1908 |

44. Sundance (Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

45. Santa Barbara (California) | July 1, 1908 |

46. Weiser (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

47. Nez Perce (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

48. Idaho (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

49. Payette (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

50. Boise (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

51. Sawtooth (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

52. Lemhi (Idaho) | July 1, 1908 |

53. Siuslaw (Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

54. Cheyenne (Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

55. Medicine Bow (Colorado), enlarged and | July 1, 1908 |

56. Cascade (Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

57. Oregon (Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

58. Umpqua (Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

59. Siskiyou (Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

60. Crater (California and Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

61. Beartooth (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

62. Holy Cross, Colorado | July 1, 1908 |

63. Targhee (Idaho and Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

64. Teton (Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

65. Wyoming (Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

66. Bonneville (Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

67. Absaroka (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

68. Beaverhead (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

69. Madison (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

70. Gallatin (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

71. Deerlodge (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

72. Helena (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

73. Missoula (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

74. Bitterroot (Idaho and Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

75. Ashley (Utah and Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

76. Uncompahgre (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

77. San Juan (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

78. Rio Grande (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

79. Pike (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

80. Montezuma (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

81. Leadville (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

82. Gunnison (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

83. Cochetopa (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

84. Arapaho (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

85. Battlement (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

86. Shoshone (Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

87. Uinta (Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

88. Crook (Arizona) | July 1, 1908 |

89. Coconino (Arizona) | July 1, 1908 |

90. Inyo (California) | July 1, 1908 |

91. Stanislaus (California) | July 1, 1908 |

92. Sierra (California) | July 1, 1908 |

93. Chiricahua (Arizona and New Mexico) | July 1, 1908 |

94. Coronado (Arizona) | July 1, 1908 |

95. Garces (Arizona) | July 1, 1908 |

96. Monterey (California) | July 1, 1908 |

97. San Isabel (Colorado) | July 1, 1908 |

98. Minidoka (Idaho and Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

99. Jefferson (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

100. Custer (Montana) | July 1, 1908 |

101. Nebraska (Nebraska) | July 1, 1908 |

102. Wallowa (Oregon) | July 1, 1908 |

103. Fishlake (Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

104. La Salle (Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

105. Wasatch (Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

106. Powell (Utah) | July 1, 1908 |

107. Bighorn (Wyoming) | July 1, 1908 |

108. Kaibab (Arizona) | July 1, 1908 |

109. Deschutes (Oregon) | July 14, 1908 |

110. Fremont (Oregon) | July 14, 1908 |

111. Ocala (Florida) | November 24, 1908 |

112. Dakota (North Dakota) | November 24, 1908 |

113. Choctawhatchee (Florida) | November 27, 1908 |

114. Humboldt (Nevada) | January 20, 1909 |

115. Moapa (Nevada) | January 21, 1909 |

116. Cleveland (California) | January 26, 1909 |

117. Pecos (New Mexico) | January 28, 1909 |

118. Prescott (Arizona) | February 1, 1909 |

119. Calaveras Bigtree (California) | February 8, 1909 |

120. Tonto (Arizona) | February 10, 1909 |

121. Marquette (Michigan) | February 10, 1909 |

122. Nevada (Nevada) | February 10, 1909 |

123. Dixie (Arizona and Utah) | February 10, 1909 |

124. Michigan (Michigan) | February 11, 1909 |

125. Klamath (California and Oregon) | February 13, 1909 |

126. Superior (Minnesota) | February 13, 1909 |

127. Gila (New Mexico) | February 15, 1909 |

128. Black Hills (South Dakota and Wyoming) | February 15, 1909 |

129. Sioux (Montana and South Dakota) | February 15, 1909 |

130. Tongass (Alaska) | February 16, 1909 |

131. Toiyabe (Nevada) | February 20, 1909 |

132. Datil (New Mexico) | February 23, 1909 |

133. Chugach (Alaska) | February 23, 1909 |

134. Modoc (California) | February 25, 1909 |

135. Ozark (Arkansas) | February 25, 1909 |

136. California (California) | February 25, 1909 |

137. Arkansas (Arkansas) | February 27, 1909 |

138. Mono (California and Nevada) | March 2, 1909 |

139. Sitgreaves (Arizona) | March 2, 1909 |

140. Lincoln (New Mexico) | March 2, 1909 |

141. Shasta (California) | March 2, 1909 |

142. Alamo (New Mexico) | March 2, 1909 |

143. Carson (New Mexico) | March 2, 1909 |

144. Zuni (Arizona and New Mexico) | March 2, 1909 |

145. Trinity (California) | March 2, 1909 |

146. Apache (Arizona) | March 2, 1909 |

147. Lassen (California) | March 2, 1909 |

148. Plumas (California) | March 2, 1909 |

149. Tahoe (California) | March 2, 1909 |

150. Sequoia (California) | March 2, 1909 |

F

EDERAL

B

IRD

R

ESERVATIONS

C

REATED BY

T

HEODORE

R

OOSEVELT, AND

A

DMITTED BY THE

B

UREAU OF

B

IOLOGICAL

S

URVEY

, USDA

Most of Roosevelt’s bird reserves are now part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s National Wildlife Refuge System (NWR) 1901–1909. Special thanks to William Reffalt, a U.S. Fish and Wildlife volunteer for helping compile this list.

Name of Bird Reservation | Date | Status | |

1. Pelican Island (Florida) | March 14, 1903 | NWR | |

enlarged | January 26, 1909 | | |

2. Breton Island (Louisiana) | October 4, 1904 | NWR | |

3. Stump Lake (North Dakota) | March 9, 1905 | NWR | |

4. Siskiwit Islands (Michigan) | October 10, 1905 | Natl. Park | |

5. Huron Islands (Michigan) | October 10, 1905 | NWR | |

6. Passage Key (Florida) | October 10, 1905 | NWR | |

7. Indian Key (Florida) | February 10, 1906 | No. Fed. Land | |

8. Tern Islands (Louisiana) | August 8, 1907 | No. Fed. Land | |

9 | August 17, 1907 | NWR | |

10. Three Arch Rocks (Oregon) | October 14, 1907 | NWR | |

11. Flattery Rocks (Washington) | October 23, 1907 | NWR | |

12. Copalis Rock (Washington) | October 23, 1907 | NWR | |

13. Quillayute Needles (Washington) | October 23, 1907 | NWR | |

14. East Timbalier Island (Louisiana) | December 7, 1907 | No. Fed. Land | |

15. Mosquito Inlet (Florida) | February 24, 1908 | No. Fed. Land | |

16. Tortugas Keys (Florida) | April 6, 1908 | Nat’l. Park | |

17. Key West (Florida) | August 8, 1908 | NWR | |

18. Klamath Lake (Oregon and California) | August 8, 1908 | NWR | |

19. Lake Malheur (Oregon) | August 18, 1908 | NWR | |

20. Chase Lake (North Dakota) | August 28, 1908 | NWR | |

21. Pine Island (Florida) | September 15, 1908 | | NWR |

22. Matlacha Pass (Florida) | September 26, 1908 | | NWR |

23. Palma Sole (Florida) | September 26, 1908 | | No. Fed. Land |

24. Island Bay (Florida) | October 23, 1908 | NWR | |

25. Loch Katrine (Wyoming) | October 26, 1908 | No Fed. Land | |

26. Hawaiian Islands | February 3, 1909 | NWR | |

27. Salt River (Arizona) | February 25, 1909 | Bur. Reel. | |

28. East Park (California) | February 25, 1909 | Impt. Reel. | |

29. Deer Flat (Idaho) | February 25, 1909 | NWR | |

30. Willow Creek (Montana) | February 25, 1909 | Other NWR | |

31. Carlsbad (New Mexico) | February 25, 1909 | Bur. Reel. | |

32. Rio Grande (New Mexico) | February 25, 1909 | Bur. Recl. | |

33. Cold Springs (Oregon) | February 25, 1909 | NWR | |

34. Belle Fourche (South Dakota) | February 25, 1909 | Impt. Recl. | |

35. Strawberry Valley (Utah) | February 25, 1909 | No. Fed. Land | |

36. Keechelus (Washington) | February 25, 1909 | Bur. Recl. | |

37. Kachess (Washington) | February 25, 1909 | Bur. Recl. | |

38. Clealum (Washington) | February 25, 1909 | Bur. Recl. | |

39. Bumping Lake (Washington) | February 25, 1909 | Bur. Recl. | |

40. Conconully (Washington) | February 25, 1909 | Impt. Recl. | |

41. Pathfinder (Wyoming) | February 25, 1909 | NWR | |

42. Shoshone (Wyoming) | February 25, 1909 | No Fed. Land | |

43. Minidoka (Idaho) | February 25, 1909 | NWR | |

44. Tuxedni (Alaska) | February 27, 1909 | Other NWR | |

45. Saint Lazaria (Alaska) | February 27, 1909 | Other NWR | |

46. Yukon Delta (Alaska) | February 27, 1909 | Other NWR | |

47. Culebra (Puerto Rico) | February 27, 1909 | NWR | |

48. Farallon (California) | February 27, 1909 | NWR | |

49. Bering Sea (Alaska) | February 27, 1909 | Other NWR | |

50. Pribilof (Alaska) | February 27, 1909 | Other NWR | |

51. Bogoslof (Alaska) | March 2, 1909 | Other NWR |