The World of Caffeine (5 page)

Read The World of Caffeine Online

Authors: Bonnie K. Bealer Bennett Alan Weinberg

Although destined for remarkable success in the Islamic world, coffee and coffee-houses met fierce opposition there from the beginning and continued to do so. Even though the leaders of some Sufi sects promoted the energizing effects of caffeine, many orthodox Muslim jurists believed that authority could be found in the Koran that coffee, because of these stimulating properties, should be banned along with other intoxicants, such as wine and hashish, and that, in any case, the new coffeehouses constituted a threat to social and political stability.

26

Considering that coffee was consumed chiefly for what we now know are caffeine’s effects on human physiology, especially the

marqaha,

the euphoria or high that it produces, it is easy to understand the reasons such scruples arose.

27

Perhaps no single episode illustrates the players and issues involved in these controversies better than the story of Kha’ir Beg, Mecca’s chief of police, who, in accord with the indignation of the ultra-pious, instituted the first ban on coffee in the first year of his appointment by Kansuh al-Ghawri, the sultan of Cairo, 1511. Kha’ir Beg was a man in the timeless mold of the reactionary, prudish martinet, reminiscent of Pentheus in Eurypides’

Bacchoe,

28

someone who was not only too uptight to have fun but was alarmed by evidence that other people were doing so. Like Pentheus, he was the butt of satirical humor and mockery, and nowhere more frequently than in the coffeehouses of the city.

Beg, as the enforcer of order, saw in the rough and ready coffeehouse, in which people of many persuasions met and engaged in heated social, political, and religious arguments, the seeds of vice and sedition, and, in the drink itself, a danger to health and well-being. To end this threat to public welfare and the dignity of his office, Beg convened an assembly of jurists from different schools of Islam. Over the heated objections of the mufti of Aden, who undertook a spirited defense of coffee, the unfavorable pronouncements of two well-known Persian physicians, called at Beg’s behest, and the testimony of a number of coffee drinkers about its intoxicating and dangerous effects ultimately decided the issue as Beg had intended.

29

Beg sent a copy of the court’s expeditious ruling to his superior, the sultan of Cairo, and summarily issued an edict banning coffee’s sale. The coffeehouses in Mecca were ordered closed, and any coffee discovered there or in storage bins was to be confiscated and burned. Although the ban was vigorously enforced, many people sided with the mufti and against the ruling of Beg’s court, while others perhaps cared more for coffee than for

sharia,

the tenants of the holy law, for coffee drinking continued surreptitiously.

To the rescue of caffeine users came the sultan of Cairo, Beg’s royal master, who may well have been in the middle of a cup of coffee himself, one prepared by his

battaghis,

the coffee slaves of the seraglio, when the Meccan messenger delivered Beg’s pronouncement. The sultan immediately ordered the edict softened. After all, coffee was legal in Cairo, where it was a major item of speculation and was, according to some reports, even used as tender in the marketplaces. Besides, the best physicians in the Arab world and the leading religious authorities, many of whom lived in Cairo at the time, approved of its use. So who was Kha’ir Beg to overturn the coffee service and spoil the party? When in the next year Kha’ir Beg was replaced by a successor who was not averse to coffee, its proponents were again able to enjoy the beverage in Mecca without fear. There is no record of whether the sultan of Cairo repented of his decision when, ten years later, in 1521, riotous brawling became a regular occurrence among caffeine-besotted coffeehouse tipplers and between them and the people they annoyed and kept awake with their late-night commotion.

In 1555, coffee and the coffeehouse were brought to Constantinople by Hakam and Shams, Syrian businessmen from Aleppo and Damascus, respectively, who made a fortune by being the first to cash in on what would become an unending Ottoman love affair with both the beverage and the institution.

30

In the middle of the sixteenth century, coffeehouses sprang up in every major city in Islam, so that, as the French nineteenth-century historian Mouradgea D’Ohsson reports in his seven-volume history of the Ottoman Empire, by 1570, in the reign of Selim II, there were more than six hundred of them in Constantinople, large and small, “the way we have taverns.” By 1573, the German physician Rauwolf, quoted above as the first to mention coffee in Europe, reported that he found the entire population of Aleppo sitting in circles sipping it. Coffee was in such general use that he believed those who told him that it had been enjoyed there for hundreds of years.

31

As a result of the efforts of Hakam and Shams and other entrepreneurs, Turks of all stations frequented growing numbers of coffeehouses in every major city, many small towns, and at inns on roads well trafficked by travelers. One contemporary observer in Constantinople noted “[t]he coffeehouses being thronged night and day, the poorer classes actually begging money in the streets for the sole object of purchasing coffee.”

32

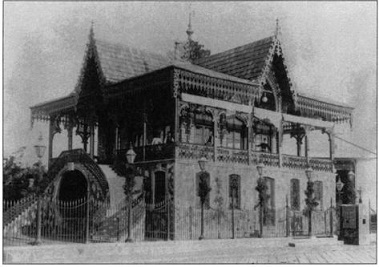

Coffee was sold in three types of establishments: stalls, shops, and houses. Coffee stalls were tiny booths offering take-out service, usually located in the business district. Typically, merchants would send runners to pick up their orders. Coffee shops, common in Egypt, Syria, and Turkey, were neighborhood fixtures, combining take-out and a small sitting area, frequently outdoors, for conversationalists. Coffeehouses were the top-of- the-line establishments, located in exclusive neighborhoods of larger cities and offering posh appointments, instrumentalists, singers, and dancers, often in gardenlike surroundings with fountains and tree-shaded tables. As these coffeehouses increased in popularity, they became more opulent. To these so-called schools of the wise flocked young men pursuing careers in law, ambitious civil servants, officers of the seraglio, scholars, and wealthy merchants and travelers from all parts of the known world. All three—shop, stall, and house—were and remain common in the Arab world, as they are in the West today.

Photograph of Café Eden, Smyrna, from an albumen photograph by Sebah and Joaillier (active 1888-c. 1900). The sign in the foreground reads “Jardin de L’Eden.” This café is typical of top-of-the-line establishments located in the better neighborhoods of the larger cities throughout the Levant. (Photograph by Sebah and Joaillier, University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, negative #s4–142210)

But the debates over the propriety of coffee use did not end with Beg’s tenure or the proliferation of the coffeehouse. Two interpretive principles continued to vie throughout these debates. On the one side was the doctrine of original permissibility, according to which everything created by Allah was presumed good and fit for human use unless it was specifically prohibited by the Koran. On the other was the mandate to defend the law by erecting a

seyag,

or “fence” around the Koran, that is, broadly construing prohibitions in order to preclude even a small chance of transgression.

The opponents of coffee drinking continued to assert their disapproval of the new habit and the disquieting social activity it seemed to engender. Cairo experienced a violent commotion in 1523, described by Walsh in his book

Coffee: Its History,

Classification, and Description

(1894):

In 1523 the chief priest in Cairo, Abdallah Ibrahim, who denounced its use in a sermon delivered in the mosque in Hassanaine, a violent commotion being produced among the populous. The opposing factions came to blows over its use. The governor, Sheikh Obelek [El-belet], a man wise in his generation and time, then assembled the mullahs, doctors, and others of the opponents of coffee-drinking at his residence, and after listening patiently to their tedious harangues against its use, treated them all to a cup of coffee each, first setting the example by drinking one himself. Then dismissing them, courteously withdrew from their presence without uttering a single word. By this prudent conduct the public peace was soon restored, and coffee was ever afterward allowed to be used in Cairo.

33

A covenant was even introduced to the marriage contract in Cairo, stipulating that the husband must provide his wife with an adequate supply of coffee; failing to do so could be joined with other grounds as a basis for filing a suit of divorce.

34

This provision shows that, even though banned from the coffeehouses, women were permitted to enjoy coffee at home.

Around 1570, by which time the use of coffee seemed well entrenched, some imams and dervishes complained loudly against it again, claiming, as Alexander Dumas wrote in his

Dictionnaire de Cuisine,

35

that the taste for the drink went so far in Constantinople that the mosques stood empty, while people flocked in increasing numbers to fill the coffeehouses. Once again the debate revived. In a curious reversal of the doctrine of original permissibility, some coffee opponents claimed that simply because coffee was

not

mentioned in the Koran, it must be regarded as forbidden. As a result coffee was again banned. However, coffee drinking continued in secret as a practice winked at by civil authorities, resulting in the proliferation of establishments reminiscent of American speakeasies of the 1920s.

Murat III, sultan of Constantinople, murdered his entire family in order to clear his way to the throne, but drew the line at allowing his subjects to debauch in the coffeehouses, and with good reason. It seems that his bloody accession was being loudly discussed there in unflattering terms, insidiously brewing sedition. In about 1580, declaring coffee

“mekreet,”

or “forbidden,” he ordered these dens of revolution shuttered and tortured their former proprietors. The religious sanction for his ban rested on the discovery, by one orthodox sect of dervishes, that, when roasted, coffee became a kind of coal, and anything carbonized was forbidden by Mohammed for human consumption.

36

His prohibition of the coffeehouse drove the practice of coffee drinking into the home, a result which, considering his purpose of dispelling congeries of public critics, he may well have counted as a success.

During succeeding reigns, the habit again became a public one, and one that, after Murat’s successor assured the faithful that roasted coffee was not coal and had no relation to it, even provided a major source of tax revenue for Constantinople. Yet in the early seventeenth century, under the nominal rule of Murat IV (1623–40), during a war in which revolution was particularly to be feared, coffee and coffeehouses became the subject of yet another ban in the city. In an arrangement reminiscent of the intrigues of the

Arabian Nights,

Murat IV’s kingdom was governed in fact by his evil vizier, Mahomet Kolpili, an illiterate reactionary who saw the coffeehouses as dens of rebellion and vice. When the bastinado was unsuccessful in discouraging coffee drinking, Kolpili escalated to shuttering the coffeehouses. In 1633, noting that hardened coffee drinkers were continuing to sneak in by the posterns, he banned coffee altogether, along with tobacco and opium, for good measure, and, on the pretext of averting a fire hazard, razed the establishments where coffee had been served. As a final remedy, as part of an edict making the use of coffee, wine, or tobacco capital offenses, coffeehouse customers and proprietors were sewn up in bags and thrown in the Bosphorus, an experience calculated to discourage even the most abject caffeine addict.

Less draconian solutions to the coffeehouse threat to social stability were implemented in Persia, notably by the wife of Shah Abbas, who had observed with concern the large crowds assembling daily in the coffeehouses of Ispahan to discuss politics. She appointed

mollahs,

expounders of religious law, to attend the coffeehouses and entertain the customers with witty monologues on history, law, and poetry. So doing, they diverted the conversation from politics, and, as a result, disturbances were rare, and the security of the state was maintained. Other Persian rulers, deciding not to stanch the flow of seditious conversation, instead placed their spies in the coffee-houses to collect warnings of threats to the security of the regime.

The coffeehouses brought with them certain unsettling innovations in Islamic society. Even those who counted themselves among the friends of coffee drinking were not entirely comfortable with the secular public gatherings, previously unheard of in respectable society, that these places made inevitable and commonplace. The freedom to assemble in a public place for refreshment, entertainment, and conversation, which was otherwise rare in a society where everyone dined at home, created as much danger as opportunity. Before the coffeehouses opened, taverns had been the only recourse for people who wanted a night out, away from home and family, and these, in Islamic lands, where tavern keepers, like prostitutes, homosexuals, and street entertainers, were shunned by respectable people. Jaziri, when chronicling the early days of coffee in the Yemen, complained, for example, that the decorum and solemnity of the Sufi

dhikr

was, in the coffeehouse, displaced by the frivolity of joking and storytelling. Worse still was malicious gossip, which, when directed against blameless women, was deemed particularly odious.