The World Was Going Our Way (73 page)

Read The World Was Going Our Way Online

Authors: Christopher Andrew

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #True Accounts, #Espionage, #History, #Europe, #Ireland, #Military, #Intelligence & Espionage, #Modern (16th-21st Centuries), #20th Century, #Russia, #World

Though anxious to withdraw from Afghanistan, Gorbachev allowed his forces to make a last major effort to defeat the

mujahideen

. During Gorbachev’s first eighteen months as Soviet leader, writes Robert Gates, then Deputy DCI, ‘we saw new, more aggressive Soviet tactics, a spread of the war to the eastern provinces, attacks inside Pakistan, and the more indiscriminate use of air power’. These eighteen months were the bloodiest of the war. With massive US assistance, the

mujahideen

held out, but the CIA operatives reported that their morale was being gradually eroded. What the

mujahideen

most lacked was state-of-the-art anti-aircraft weapons. Zia had told Casey in April 1982: ‘The Pathans [Pushtun] are great fighters but shit-scared when it comes to air-power.’ When the CIA supplied shoulder-launched US Stinger missiles to the

mujahideen

in the summer of 1986, they had a major, perhaps even decisive, impact on the war.

46

On 25 September a group of Hekmatyar’s

mujahideen

armed with Stingers shot down three Soviet helicopter gunships as they approached Jalalabad airport. DCI Casey personally showed President Reagan a dramatic video of the attack taken by the

mujahideen

, the soundtrack mingling the sound of explosions with cries of

Allahu Akhbar!

Shebarshin did not immediately grasp the significance of the

mujahideen

’s use of the Stingers. Early in October the GRU obtained two of the missiles from agents in the

mujahideen

, and he expected effective counter-measures to be devised.

47

As the Soviet Defence Ministry complained, the Stingers marked ‘a qualitatively new stage in Washington’s interference’ in the war. ‘Although the Soviet and Afghan air forces adjusted their tactics to reduce losses, they effectively lost a trump card in the war - control of the air.’

48

By 1987 the CIA station in Islamabad was co-ordinating the provision of over 60,000 tons per year of weapons and other supplies to the

mujahideen

along over 300 infiltration routes by five- and ten-ton trucks, smaller pick-ups and pack mules. Milt Bearden, the station chief, ‘discovered that on an annual basis we needed more mules than the world seemed prepared to breed’.

49

mujahideen

. During Gorbachev’s first eighteen months as Soviet leader, writes Robert Gates, then Deputy DCI, ‘we saw new, more aggressive Soviet tactics, a spread of the war to the eastern provinces, attacks inside Pakistan, and the more indiscriminate use of air power’. These eighteen months were the bloodiest of the war. With massive US assistance, the

mujahideen

held out, but the CIA operatives reported that their morale was being gradually eroded. What the

mujahideen

most lacked was state-of-the-art anti-aircraft weapons. Zia had told Casey in April 1982: ‘The Pathans [Pushtun] are great fighters but shit-scared when it comes to air-power.’ When the CIA supplied shoulder-launched US Stinger missiles to the

mujahideen

in the summer of 1986, they had a major, perhaps even decisive, impact on the war.

46

On 25 September a group of Hekmatyar’s

mujahideen

armed with Stingers shot down three Soviet helicopter gunships as they approached Jalalabad airport. DCI Casey personally showed President Reagan a dramatic video of the attack taken by the

mujahideen

, the soundtrack mingling the sound of explosions with cries of

Allahu Akhbar!

Shebarshin did not immediately grasp the significance of the

mujahideen

’s use of the Stingers. Early in October the GRU obtained two of the missiles from agents in the

mujahideen

, and he expected effective counter-measures to be devised.

47

As the Soviet Defence Ministry complained, the Stingers marked ‘a qualitatively new stage in Washington’s interference’ in the war. ‘Although the Soviet and Afghan air forces adjusted their tactics to reduce losses, they effectively lost a trump card in the war - control of the air.’

48

By 1987 the CIA station in Islamabad was co-ordinating the provision of over 60,000 tons per year of weapons and other supplies to the

mujahideen

along over 300 infiltration routes by five- and ten-ton trucks, smaller pick-ups and pack mules. Milt Bearden, the station chief, ‘discovered that on an annual basis we needed more mules than the world seemed prepared to breed’.

49

By the spring of 1986, Gorbachev had decided on the replacement of Karmal as Afghan leader by the much tougher but also more flexible head of KHAD, Muhammad Najibullah, who had the strong backing of the Centre. Early in May Gorbachev bluntly told Karmal that he should hand over power to Najibullah and retire to Moscow with his family. There followed what Anatoli Dobrynin, the only other person present, described as a ‘painful’ scene in which Karmal ‘obsequiously begged Gorbachev to change his mind, promising to perform his duties in a more correct and active way’.

50

Gorbachev refused and Kabul Radio, using a traditional Soviet euphemism for dismissal, announced that the PDPA Central Committee had accepted Karmal’s request to resign for ‘health reasons’ and elected Najibullah in his stead. As a sop to the wounded pride of Karmal and his supporters he was allowed to retain his membership of the PDPA Politburo and to continue to serve as President of the Afghan Revolutionary Council.

51

To Gorbachev’s fury, however, Karmal contrived to hold on to some of his former power. He was finally forced to resign from the Politburo and the presidency of the Revolutionary Council in November.

52

50

Gorbachev refused and Kabul Radio, using a traditional Soviet euphemism for dismissal, announced that the PDPA Central Committee had accepted Karmal’s request to resign for ‘health reasons’ and elected Najibullah in his stead. As a sop to the wounded pride of Karmal and his supporters he was allowed to retain his membership of the PDPA Politburo and to continue to serve as President of the Afghan Revolutionary Council.

51

To Gorbachev’s fury, however, Karmal contrived to hold on to some of his former power. He was finally forced to resign from the Politburo and the presidency of the Revolutionary Council in November.

52

The outcome of the war in Afghanistan was sealed at a dramatic meeting of the Politburo on 13 November 1986. A year earlier, Gorbachev had given the army a last chance to defeat the

mujahideen

or at least to create the illusion of victory. Now he was determined to bring the war to an end and made an unprecedented criticism of the Soviet high command:

mujahideen

or at least to create the illusion of victory. Now he was determined to bring the war to an end and made an unprecedented criticism of the Soviet high command:

We have been fighting in Afghanistan for six years already. Unless we change our approach, we shall continue to fight for another 20-30 years . . . Our military should be told they are learning badly from this war . . . Are we going to fight endlessly, as a testimony that our troops are not able to deal with this situation? We need to finish this process as quickly as possible.

Gorbachev set a target of two years for withdrawing all Soviet troops, but was anxious to ensure that ‘the Americans don’t get into Afghanistan’ as a result.

53

Chernyaev believed that Soviet troops could have been withdrawn in two months. The reason for the delay was essentially to avoid losing face after the long struggle for influence with the United States in the Third World: ‘The Afghan problem, as in the beginning of that adventure, was still seen primarily in terms of “global confrontation” and only secondarily in light of the “new thinking”.’

54

53

Chernyaev believed that Soviet troops could have been withdrawn in two months. The reason for the delay was essentially to avoid losing face after the long struggle for influence with the United States in the Third World: ‘The Afghan problem, as in the beginning of that adventure, was still seen primarily in terms of “global confrontation” and only secondarily in light of the “new thinking”.’

54

At Gorbachev’s proposal, the Politburo appointed a new Afghanistan Commission, chaired by Eduard Shevardnadze, Gromyko’s successor as Foreign Minister.

55

Shevardnadze’s oral report to the Politburo two months later was, by implication, a devastating indictment of the distortions in previous intelligence and other reports to the leadership which had sought to conceal the extent of the failure of Soviet Afghan policy:

55

Shevardnadze’s oral report to the Politburo two months later was, by implication, a devastating indictment of the distortions in previous intelligence and other reports to the leadership which had sought to conceal the extent of the failure of Soviet Afghan policy:

Little remains of the friendly feelings [in Afghanistan] toward the Soviet Union which existed for decades. A great many people have died and not all of them were bandits. Not one problem has been solved to the peasantry’s advantage. The government bureaucracy is functioning poorly. Our advisers’ aid is ineffective. Najib complains of the narrow-minded tutelage of our advisers.

I won’t discuss right now whether we did the right thing by going in there. But we did go in there absolutely without knowing the psychology of the people and the real state of affairs in the country. That’s a fact. And everything that we’ve done and are doing in Afghanistan is incompatible with the moral character of our country.

The Prime Minister, Nikolai Ivanovich Rhyzhkov, praised Shevardnadze’s report as the first ‘realistic picture’ of the situation in Afghanistan: ‘Previous information was not objective.’ Even the hard-liner Yegor Ligachev agreed that Shevardnadze had provided ‘the first objective information’ received by the Politburo. Chebrikov, the KGB Chairman, who was a member of the Afghanistan Commission, attempted a half-hearted defence of previous intelligence reporting, claiming that, though the Politburo appeared to have ‘received much new material’, that material could be found in earlier reports. None the less, he agreed with the conclusions of the rest of the Politburo on the Afghan situation: ‘The Comrades have analysed it well.’

56

56

As Gorbachev acknowledged, ‘They panicked in Kabul when they found out we intended to leave.’

57

In implementing the decision to withdraw, he also had to cope with a rearguard action mounted by some sections of the Centre and the military. He retaliated with a series of public disclosures which revealed that Soviet military intervention had been decided by a small clique within the Politburo that had put pressure on Brezhnev.

58

57

In implementing the decision to withdraw, he also had to cope with a rearguard action mounted by some sections of the Centre and the military. He retaliated with a series of public disclosures which revealed that Soviet military intervention had been decided by a small clique within the Politburo that had put pressure on Brezhnev.

58

In January 1989, a month before the final withdrawal of the last Soviet forces, the Politburo’s Afghanistan Commission reported that ‘the Afghan comrades are seriously worried about how the situation will turn out’. The comrades were, however, encouraged by the ‘strong disagreements’ within the

mujahideen

, particularly the mutual hostility between the Pushtun forces of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and the Tajik forces of Burhanudeen Rabbani and Massoud: ‘Armed clashes between detachments of these and other opposition groups are not just continuing, but are taking on wider proportions as well.’

59

Though Mitrokhin retired too early to see KGB files on the later stages of the war, there can be no doubt that promoting divisions within the

mujahideen

and provoking further armed clashes between them remained a major priority of KGB and KHAD operations. While these divisions did not derive from KGB active measures, they were doubtless exacerbated by them. Hekmatyar’s publicly stated conviction that, despite supplying him with arms, the CIA was plotting his assassination

60

has all the hallmarks of deriving from a KGB disinformation operation.

mujahideen

, particularly the mutual hostility between the Pushtun forces of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar and the Tajik forces of Burhanudeen Rabbani and Massoud: ‘Armed clashes between detachments of these and other opposition groups are not just continuing, but are taking on wider proportions as well.’

59

Though Mitrokhin retired too early to see KGB files on the later stages of the war, there can be no doubt that promoting divisions within the

mujahideen

and provoking further armed clashes between them remained a major priority of KGB and KHAD operations. While these divisions did not derive from KGB active measures, they were doubtless exacerbated by them. Hekmatyar’s publicly stated conviction that, despite supplying him with arms, the CIA was plotting his assassination

60

has all the hallmarks of deriving from a KGB disinformation operation.

Contrary to a public declaration by Gorbachev, 200 military and KGB advisers secretly remained behind in Kabul after the last Soviet troops had gone. As the Najibullah regime began to crumble in April 1992, having defied all predictions by outlasting the Soviet Union, Boris Yeltsin, the President of the Russian Federation, was surprised to discover the continued presence of the advisers and immediately withdrew them.

61

The fall of Najibullah was swiftly followed by civil war among the

mujahideen

. Much of the chaos which preceded the conquest of Kabul in 1996 by the extreme fundamentalist Taleban was the product of the war which had followed the Soviet invasion in 1979 - and of the secret war in particular. More than any other conflict in history, the war in Afghanistan was shaped by the covert operations of foreign intelligence agencies. The KGB, the CIA, the Pakistani ISI, the Saudi General Intelligence Department and Iranian clandestine services all trained, financed and sought to manipulate rival factions in Afghanistan.

62

These rival factions in turn helped to reduce Afghanistan after fourteen years of disastrous Communist misrule to a chaotic conglomeration of rival warlords.

61

The fall of Najibullah was swiftly followed by civil war among the

mujahideen

. Much of the chaos which preceded the conquest of Kabul in 1996 by the extreme fundamentalist Taleban was the product of the war which had followed the Soviet invasion in 1979 - and of the secret war in particular. More than any other conflict in history, the war in Afghanistan was shaped by the covert operations of foreign intelligence agencies. The KGB, the CIA, the Pakistani ISI, the Saudi General Intelligence Department and Iranian clandestine services all trained, financed and sought to manipulate rival factions in Afghanistan.

62

These rival factions in turn helped to reduce Afghanistan after fourteen years of disastrous Communist misrule to a chaotic conglomeration of rival warlords.

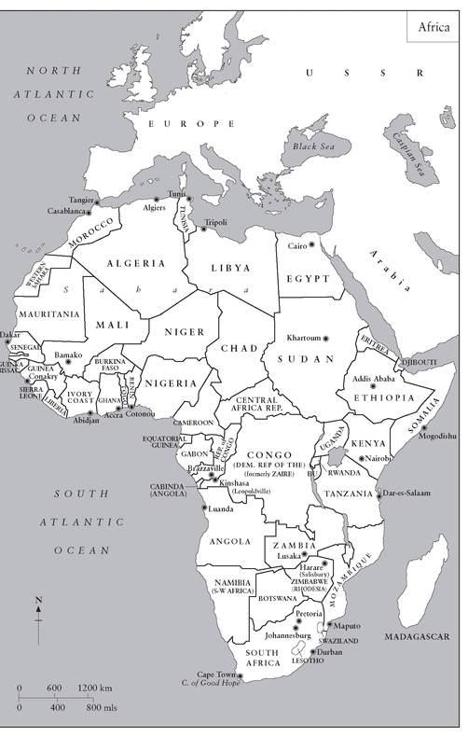

Africa

23

Africa: Introduction

Of all the African countries, both Lenin and Comintern were most interested in South Africa. The very first issue of the Marxist newspaper

Iskra

, which Lenin began editing in 1900, mentioned South Africa twice. Like Lenin, Comintern looked to South Africa, the most industrialized and urbanized country on the continent, as the future vanguard of the African Revolution. In 1922 Bill Andrews, the first Chairman of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), joined Comintern’s Executive Committee. In 1927 the African National Congress (ANC) elected as its President the pro-Communist Josiah Gumede, who visited Moscow and became head of the South African section of the newly founded Soviet front organization, the League Against Imperialism.

1

During the mid- 1920s African and American blacks began to study in Moscow’s secret Comintern-run International Lenin School (MLSh) and Communist University of the Toilers of the East (KUTV). All were given false identities during their time in Moscow and their curriculum, like that of the other students, included training in underground work, espionage and guerrilla warfare. The Comintern leadership, however, had low expectations of all but the South Africans. Like other Soviet leaders, Grigori Zinoviev, the Comintern Chairman, knew little about black Africa. When he came to lecture at the KUTV in 1926, an Ashanti student from the Gold Coast, Bankole Awanoore-Renner, asked him about ‘Comintern’s attitude toward the oppressed nations of Africa’. Zinoviev responded by talking in some detail about the problems of Morocco and Tunisia, but Awanoore-Renner complained that he said nothing about ‘the most oppressed people’ south of the Sahara. Though Zinoviev pleaded lack of information, Awanoore-Renner thought he detected the stench of racism.

Iskra

, which Lenin began editing in 1900, mentioned South Africa twice. Like Lenin, Comintern looked to South Africa, the most industrialized and urbanized country on the continent, as the future vanguard of the African Revolution. In 1922 Bill Andrews, the first Chairman of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA), joined Comintern’s Executive Committee. In 1927 the African National Congress (ANC) elected as its President the pro-Communist Josiah Gumede, who visited Moscow and became head of the South African section of the newly founded Soviet front organization, the League Against Imperialism.

1

During the mid- 1920s African and American blacks began to study in Moscow’s secret Comintern-run International Lenin School (MLSh) and Communist University of the Toilers of the East (KUTV). All were given false identities during their time in Moscow and their curriculum, like that of the other students, included training in underground work, espionage and guerrilla warfare. The Comintern leadership, however, had low expectations of all but the South Africans. Like other Soviet leaders, Grigori Zinoviev, the Comintern Chairman, knew little about black Africa. When he came to lecture at the KUTV in 1926, an Ashanti student from the Gold Coast, Bankole Awanoore-Renner, asked him about ‘Comintern’s attitude toward the oppressed nations of Africa’. Zinoviev responded by talking in some detail about the problems of Morocco and Tunisia, but Awanoore-Renner complained that he said nothing about ‘the most oppressed people’ south of the Sahara. Though Zinoviev pleaded lack of information, Awanoore-Renner thought he detected the stench of racism.

In September 1932 mounting complaints of racism in Moscow by black African and American students led Comintern’s Executive Committee to appoint an investigative committee. In January 1933 Dmitri Manuilsky, who had succeeded Zinoviev as Comintern chief, came to the University to listen to their complaints, which included a letter complaining of the ‘derogatory portrayal of Negroes in the cultural institutions of the Soviet Union’ as ‘real monkeys’. The signatures included the name ‘James Joken’, the Moscow alias of Jomo Kenyatta, later the first leader of independent Kenya.

2

For Kenyatta, as for many radical African students a generation later, life in the Soviet Union was a disillusioning experience. Before he left for Moscow the Special Branch in London believed that he had joined the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and that a leading British Communist, Robin Page Arnott, had spoken of him prophetically as ‘the future revolutionary leader of Kenya’.

3

Kenyatta’s lecturers at the KUTV in Moscow were less enthusiastic. Though assessing him as ‘a very intelligent and well educated negro’, the KUTV lecturers’ collective reported that ‘He contrasted our school with the bourgeois school, stating that in all respects the bourgeois school is superior to ours. In particular, the bourgeois school teaches [its pupils] to think and provides the opportunity to do so, evidently thinking that our school does not provide this opportunity.’ The collective recommended after Kenyatta’s graduation in May 1933 that he be given three to four months further ‘fundamental’ instruction in Marxist-Leninist theory by an experienced teacher before returning to Kenya.

4

2

For Kenyatta, as for many radical African students a generation later, life in the Soviet Union was a disillusioning experience. Before he left for Moscow the Special Branch in London believed that he had joined the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) and that a leading British Communist, Robin Page Arnott, had spoken of him prophetically as ‘the future revolutionary leader of Kenya’.

3

Kenyatta’s lecturers at the KUTV in Moscow were less enthusiastic. Though assessing him as ‘a very intelligent and well educated negro’, the KUTV lecturers’ collective reported that ‘He contrasted our school with the bourgeois school, stating that in all respects the bourgeois school is superior to ours. In particular, the bourgeois school teaches [its pupils] to think and provides the opportunity to do so, evidently thinking that our school does not provide this opportunity.’ The collective recommended after Kenyatta’s graduation in May 1933 that he be given three to four months further ‘fundamental’ instruction in Marxist-Leninist theory by an experienced teacher before returning to Kenya.

4

Other books

Thirty-Two and a Half Complications by Denise Grover Swank

Unwrapping Mr. Roth by Holley Trent

The Coldest War by Ian Tregillis

Midnight Before Christmas by William Bernhardt

The Surprising Power of Liberating Structures: Simple Rules to Unleash A Culture of Innovation by Henri Lipmanowicz, Keith McCandless

The Mage of Orlon: The beginning by Gene Rager

The Witch's Desire by Elle James

The Devil Gun by J. T. Edson

Love Me Not by Villette Snowe

A Cold and Lonely Place: A Novel by Henry, Sara J.