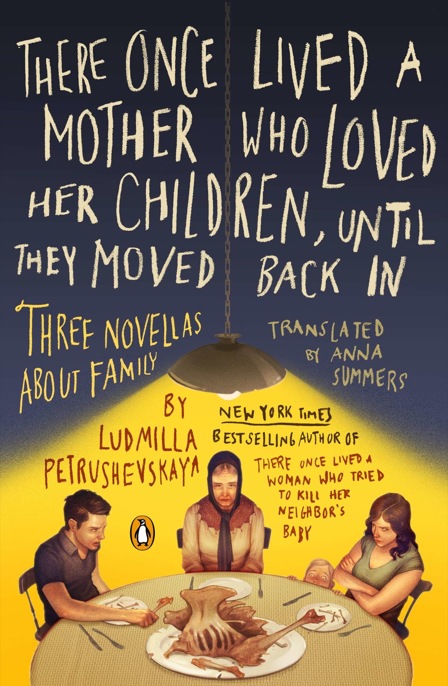

There Once Lived a Mother Who Loved Her Children, Until They Moved Back In

Read There Once Lived a Mother Who Loved Her Children, Until They Moved Back In Online

Authors: Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

Acclaim for Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

“Petrushevskaya writes instant classics.”

—

The Daily Beast

“Her suspenseful writing calls to mind the creepiness of Poe and the psychological acuity (and sly irony) of Chekhov.”

—

More

“What distinguishes the author is her compression of language, her use of detail, and her powerful visual sense.”

—

Time Out New York

“The fact that Ludmilla Petrushevskaya is Russia’s premier writer of fiction today proves that the literary tradition that produced Dostoyevsky, Gogol, and Babel is alive and well.”

—Taylor Antrim,

The Daily Beast

“A master of the Russian short story.”

—Olga Grushin, author of

The Dream Life of Sukhanov

“There is no other writer who can blend the absurd and the real in such a scary, amazing, and wonderful way.”

—Lara Vapnyar, author of

There Are Jews in My House

“One of the greatest writers in Russia today and a vital force in contemporary world literature.”

—Ken Kalfus, author of

A Disorder Peculiar to the Country

“A master of the short story form, a kindred spirit to writers like Angela Carter and Yumiko Kurahashi.”

—Kelly Link, author of

Magic for Beginners and Stranger Things Happen

PENGUIN BOOKS

There Once Lived a Mother Who Loved Her Children, Until They Moved Back In

LUDMILLA PETRUSHEVSKAYA

was born in 1938 in Moscow, where she still lives. She is the author of more than fifteen volumes of prose, including the

New York Times

bestseller

There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby: Scary Fairy Tales

, which won a World Fantasy Award and was one of

New York

magazine’s Ten Best Books of the Year and one of NPR’s Five Best Works of Foreign Fiction, and

There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself: Love Stories.

A singular force in modern Russian fiction, she is also a playwright whose work has been staged by leading theater companies all over the world. In 2002 she received Russia’s most prestigious prize, the Triumph, for lifetime achievement.

ANNA SUMMERS

is the coeditor and cotranslator of Ludmilla Petrushevskaya’s

There Once Lived a Woman Who Tried to Kill Her Neighbor’s Baby: Scary Fairy Tales

and the editor and translator of Petrushevskaya’s

There Once Lived a Girl Who Seduced Her Sister’s Husband, and He Hanged Himself: Love Stories

. Born and raised in Moscow, she now lives in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she is the literary editor of

The Baffler

.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

A Penguin Random House Company

First published in Penguin Books 2014

Copyright © 1988, 1992, 2002 by Ludmilla Petrushevskaya

Translation and introduction copyright © 2014 by Anna Summers

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

In the original Russian “Among Friends” and “The Time Is Night” were published in issues of

Novy Mir

and “Chocolates with Liqueur” in the collection

The Goddess Parka

(Vagrius, Moscow). Anna Summers’ translation of “Among Friends” appeared in

The Baffler

.

Published with the support of the Institute for Literary Translation (Russia)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Petrushevskaia, Liudmila

[Novellas. Selections. English. 2014]

There once lived a mother who loved her children, until they moved back in : three novellas about family / Ludmilla Petrushevskaya ; translated by Anna Summers ; introduction by Anna Summers.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-14182-7

1. Petrushevskaia, Liudmila—Translations into English. 2. Domestic fiction, Russian—Translations into English. I. Summers, Anna, translator. II. Petrushevskaia, Liudmila. Vremia noch’. English. III. Petrushevskaia, Liudmila. Konfety s likerom. English. IV. Petrushevskaia, Liudmila. Svoi krug. English. V. Title. VI. Title: Time is night. VII. Title: Chocolates with liqueur. VIII. Title: Among friends.

PG3485.E724A2 2014

891.73’44—dc23 2014012797

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Art direction: Roseanne Serra

Cover illustration: Sam Wolfe Connelly

Version_1

This translation is dedicated to my loving husband, John, and to the memories of my mother, Irina Viktorovna Malakhova, and grandmother Klavdiya Kirillovna Malakhova.

Contents

ACCLAIM FOR LUDMILLA PETRUSHEVSKAYA

Introduction

R

ussian is a story-swapping culture. Bring your children to a playground, sit yourself down on a bench next to other sunflower-seed-crunching moms, and in ten minutes you’ll know whose husband drinks, whose younger sister got pregnant by an unknown party, and who was insulted, again, by her mother-in-law, because they all live together, and so on. But some stories a stranger won’t hear. Shameful stories—shameful by Russian standards; stories that mix violence, insanity, and jail. What they call

extremal

in Russian—stories too extreme for casual tale-swapping, suitable only for furtive whispering.

For example, a family of five, say, is living in a three-room apartment in Moscow in the mideighties. They have just enough. Mother and father work, the roof doesn’t leak, there are staples in the cupboards, an occasional delicacy in the fridge. There are even two crystal vases on the shelves. One day, while the grandmother and the children are out at a New Year’s pageant, the mother tries to kill the father with an ax. That’s it. The father disappears to the ER; the mother disappears to a hospital for the insane, to await trial; the crystal vases get sold to pay for the mother’s defense; six months later the mother comes home to a wasteland. With her remaining strength she tries to raise the children, while the grandmother grows more and more demented; finally the mother gets cancer. The end.

This would make a typical Ludmilla Petrushevskaya story. But it also happened in my house, to my family, many years ago. We didn’t know at the time there were stories written for us, about us; in the Soviet Union, as the narrator in

Among Friends

notes wryly, everyone lived as though on a desert island, and especially families like mine, families traumatized—and stigmatized—by

extremal

. Petrushevskaya’s work was suppressed for decades; only later, after the Soviet Union’s collapse, did we find out that all those years when we knew only shame and neglect, in the same city a woman exactly my mother’s age, also a mother, was composing story after story and play after play about families like ours—ordinary families who had suffered a tragedy.

• • •

The three novellas in this volume tell extreme stories that couldn’t be heard for many years—censorship wouldn’t allow it. Petrushevskaya was unable to publish

Among Friends

for seventeen years; it existed as samizdat.

The Time Is Night

was published in Germany in translation before it came out in Russia. When

Among Friends

and

The Time Is Night

finally appeared, they weren’t alone: a whole wave of previously suppressed works was released at the same time. It turned out that a number of brilliant writers had been trying to tell their own extreme tales about life in the Soviet Union, which was so opaque, so completely shrouded from both the West and its own citizens, that it was impossible to tell what was happening next door, let alone in Siberia. Fedor Abramov wrote about the devastation in the Russian countryside, the sufferings of the millions of peasants; Chinghiz Aitmatov about the government corruption and environmental disasters in Central Asia; Sergei Dovlatov about the horrors of army life; Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Varlam Shalamov about arrests, interrogations, political prisons, and camps; Andrey Platonov about the civil war and the Bolshevik revolution.

And Petrushevskaya? She described in minute detail how ordinary people, Muscovites, lived from day to day in their identical cramped apartments: how they loved, how they dreamed, how they raised their children, how they took care of their elders, and how they died. She spoke for all those who suffered domestic hell in silence, the way Solzhenitsyn spoke for the countless nameless political prisoners. To write about, say, the woman next door who worked for the post office, some bedraggled Aunt Masha who was left by her husband to raise three children on a salary of ninety rubles when a pair of shoes cost twenty, if you could find them, and who had to care for her paralyzed mother while her teenage son wreaked havoc (all details from Petrushevskaya’s stories), took as much art and as much courage as describing one day in the life of Ivan Denisovich. The difference was that Petrushevskaya’s subjects were closer to home—they weren’t exiled out of our sight, out of our mind. They lived across the hall; they shared the room with us; they were my mother and grandmother.

As both her critics and admirers agree, reading Petrushevskaya is an unforgettable experience. This testifies to the exceptional power of her art, because her characters, by their own admission, don’t make particularly fascinating subjects. In this volume, her heroines are tired, scared, impoverished women who have been devastated by domestic tragedies and who see little beyond the question, How to raise a child? How to feed it, clothe it, educate it when there is no strength left and no resources? Such women are boring even to themselves. Anna, the heroine of

The Time Is Night

, complains that no one wants to know how she lives: not her former friends or colleagues, not the state, not her neighbors—she herself can barely stand it. No one wants to know, except for Petrushevskaya. She takes it upon herself to describe her drab characters in such a way that we can’t put the book down, and when we finish reading we are overwhelmed by the most profound empathy.