This Book Is Not Good For You (18 page)

Read This Book Is Not Good For You Online

Authors: Pseudonymous Bosch

A pair of large gloved hands threw Cass onto the cement floor of an old animal cage and closed the iron bars with an angry clang.

Blearily, Cass recognized her large lumbering jailer as Daisy, Ms. Mauvais’s toughest and most loyal servant. Had Daisy recognized Cass earlier after all? Had she just been playing her part in conspiring to get Cass to eat the chocolate?

The answer, judging by Daisy’s smug and self-satisfied expression, was YES.

What a sucker I am, Cass thought bitterly. She had come to rescue her mother, and she’d succeeded only in getting imprisoned herself!

Without saying anything, Daisy took up position as guard in front of Cass’s cage. A ring of keys hung from Daisy’s hip, tantalizingly out of reach.

Thinking of ways she could possibly snatch it, Cass fell back asleep.

An hour or so later, she stirred.

A girl of about her own age was hovering over her.

“Hi, you eat the chocolate, yes?” she asked in a thick French accent.

“Yeah, how did you know?”

“Your eyes. They do this—”

She rolled her eyes in the back of her head, so only the whites of her eyes showed.

“That’s a good trick,” said Cass, pushing herself up. “You could really make somebody think you were unconscious or crazy or something. Could be useful in an emergency or if somebody took you prisoner.”

“But I am a prisoner,” said Simone, not fully understanding. “My name is Simone.”

“Hi, I’m Cass.”

Simone looked at her in surprise. “Cass? Like Cassandra?”

“Yeah, why is that so weird?”

“You are the daughter of Melanie?”

Suddenly, Cass was sitting bolt upright.

“You know my mom?”

Simone nodded. “She is a very nice lady. For one day, she lived with me. She helped me speak English. Then they moved her because they do not want us to be friends.”

Cass grabbed Simone’s wrist. “Where is she now?”

“She is in jail also. There—” Simone pointed with her free hand to the cement wall next to them.

“She’s next door?” Cass couldn’t contain herself any longer. She moved over to the bars and shouted as loud as she could.

“Mom?!”

For a moment, there was no response. Then a tentative voice:

“Cass?”

“Yeah, I’m right next door!”

A tear rolled down Cass’s cheek. She was so relieved her mother was alive. And so sad they were both prisoners.

“What are you doing here, sweetheart? Did they take you, too? Are you OK?” Her mother sounded sick with worry.

“I’m fine, Mom!”

Mom. She’d said it without thinking. As if it were all she’d ever called her. And, Cass decided right then and there, it was all she would ever call her in the future.

“Quiet!” Daisy shouted, hitting their cage doors as she walked past them. “I’m going to eat my lunch now. If I hear another word, I’m putting my mamba in there with you. You’ll survive just long enough for your mother to hear you scream.”

Well, at least she’s learned something from Ms. Mauvais, Cass reflected: how to issue a good threat.

Simone muttered something in French that Cass took to mean she should do what Daisy said.

“Oh, I can handle Daisy—I have before,” Cass boasted.

Simone shrugged, pointing across the yard—

Daisy, now sitting down on a bench with her back to the cages, was adorned with a long green snake. Hissing, it slithered up her shoulder and around her neck. It glared menacingly at Cass.

Daisy nuzzled the back of the snake’s head, then offered it her sandwich. “Do you want a little yum yum, Peaches?” she asked loudly.

Peaches bared her fangs, then darted forward and swallowed the entire sandwich in a single bite.

“OK, maybe you’re right,” said Cass, slinking back against the stone wall.

“Your mother, she loves you very much,” whispered Simone. “You are very lucky.”

“Thanks, Simone,” said Cass, meaning it.

She closed her eyes. If Daisy looked over, she would think Cass had fallen back asleep. Meanwhile, her mind was racing. At last, she’d found her mother! There was some comfort just knowing they were so close. But how to communicate when Daisy was only twenty feet away? She could try tapping on the wall. But it looked so thick, she doubted her mother would hear. Besides, she was fairly certain her mother didn’t know Morse code.

She was awakened from her reverie by the sound of tapping— not on the wall next to her, but on the iron bars in front of her. It was the quetzal, the green bird who’d proven so helpful in locating the chocolate plantation. He was perched on the edge of the cement slab, tapping on the end of a bar.

Simone held out a small, broken piece of chocolate—the bird pecked it away.

“You are going to get very fat, my friend,” said Simone to the bird. She turned to Cass, explaining, “Now because I am here, and your mom is there—he thinks he can eat and eat and eat!” She spoke softly so as not to attract attention.

“You mean my mom feeds him, too?”

“Yes. He flies back and forth, back and forth.”

Cass thought about this for a minute, then glanced over at Daisy: luckily, she was still sitting on the bench, stroking her green mamba.

“Hey, do you have a pencil?”

Simone looked confused, so Cass picked up a piece of newspaper off the floor and mimed writing on it.

Simon smiled. “Ah, yes—for writing. Sorry, I have nothing… oh, wait, maybe this?” She handed Cass another small lump of chocolate. “Do not worry. It is the old chocolate. Not the kind that makes the dreams.”

“I’m not worried—I’m not going to eat it.”

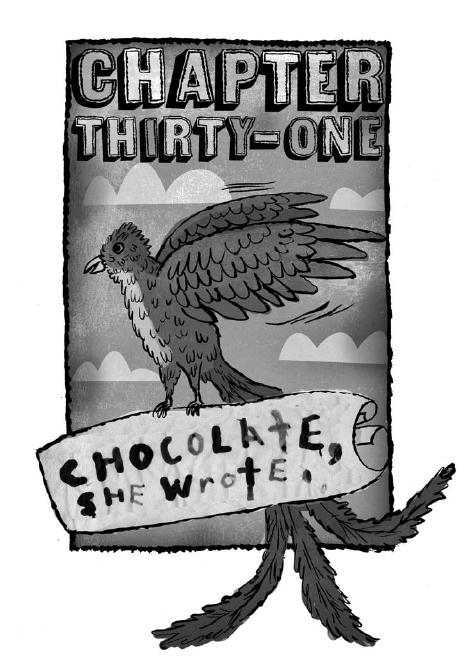

Using the chocolate as a crayon, Cass wrote a note to her mother as quickly as possible. She was trying to finish before the chocolate melted in her hand. *

Dear Mom,

Sorry about what I said. You are my real mom and always will be. I love you.

Love, Cass

P.S. Simone gave me this chocolate. After you write back, give the bird the rest of it and hopefully he will bring the note back.

After she finished writing, she rolled up the piece of chocolate in the newspaper and placed it in front of the bird. She was afraid the bird wouldn’t take the note, since she had no more chocolate to offer. But the bird took pity—or perhaps hoped there would be more chocolate to come—and he readily gripped the scroll and flapped his wings.

About five minutes later, the quetzal landed in front of Cass’s cage with a flutter of wings. He seemed rather proud of himself.

In his claws, he clutched the roll of newspaper.

Checking again to make sure Daisy wasn’t watching, Cass reached through the bars and took the newspaper.

Turning so she wouldn’t be visible from the outside, she unfurled the paper. It was ripped and smudged—and, from the looks of it—nibbled by a chocolate-loving bird. But she could read most of what it said.

After reading the note three times, Cass folded it carefully, her eyes teary.

Her mother didn’t hate her! Even after the terrible thing Cass had said. Her mother thought she was a hero. Cass didn’t feel much like a hero—she couldn’t get over the fact that it was her fault her mother was here—but heroism was something to aspire to anyway.

Obviously, the heroic thing at this moment would be to stage a daring escape and then rescue her mom. But how could she do that with Daisy and her mamba guarding the zoo-jail?

As Cass contemplated this conundrum, she heard a bloodcurdling cry. It sounded oddly like—

Note: Chapter 31 continues on page 319.

?

Continued from page 303.

Max-Ernest’s hunch proved correct: the Midnight Sun had installed a trapdoor in the floor of a broom closet. He dropped down through it to the ground below, nearly spraining his ankle but not quite.

The underside of the Pavilion was nearly a full story high, and Max-Ernest could easily stand without hitting his head. Nonetheless, he walked in a crouch, trying to hide behind the pillars as much as possible.

As soon he was out from under the building he saw a line of muddy footprints leading into the rainforest—two sets going in, one going out.

Max-Ernest peered down at the smaller set. Sneakers. He didn’t remember the brand of Yo-Yoji’s prize pair, but he was certain these were his.

He followed the footprints, ducking branches and hopping tree roots, until he reached a large pool of muddy water.

Here Yo-Yoji’s footprints died.

Max-Ernest shuddered: could they have thrown Yo-Yoji in? In his condition, he almost certainly would have drowned.

Bracing himself for the worst, Max-Ernest started looking for a stick with which to poke the water.

“Hai!”

Startled, Max-Ernest turned. He didn’t see anyone. Who was it?

“Hai!”

The voice was low and deep. Almost a growl.

“Hai!”

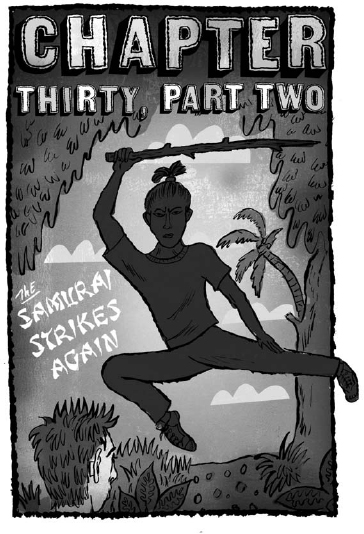

It didn’t sound anything like Yo-Yoji, but when Max-Ernest pushed aside a bush (or what was once a bush) he saw his friend (or what was once his friend) brandishing a stick (or what was once a stick; it was now whittled into something more closely resembling a sword).

Aside from the fact that he had pulled up his long bangs into one those short forehead-ponytails worn by sumo wrestlers, Yoji-Yoji’s physical features had not changed. And yet he was utterly transformed. His facial expressions, his movements, the look in his eyes—all belonged to someone else.

“Hai!” said Yo-Yoji. He was facing Max-Ernest’s direction but seemed to be looking at a point beside or behind him, as if he couldn’t quite see Max-Ernest.

“Er, hi,” said Max-Ernest.