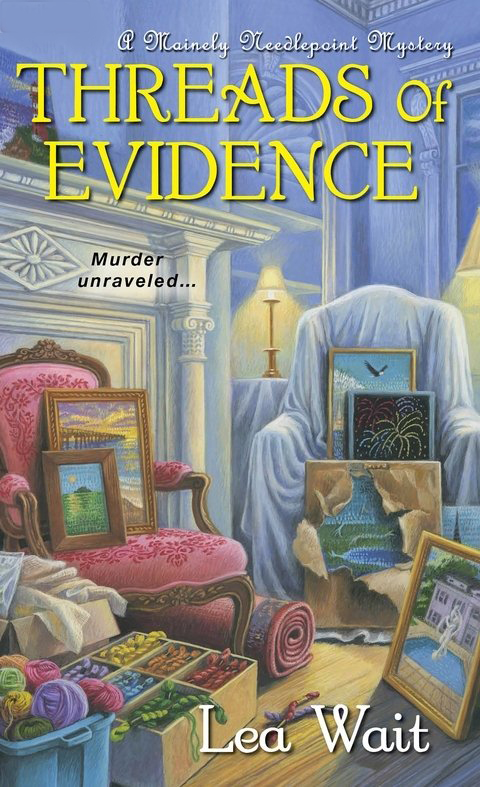

Threads of Evidence

Read Threads of Evidence Online

Authors: Lea Wait

KILLER LEMONADE

“Look!” I whispered and pointed. We all held our breaths as a male ruby-throated hummingbird hovered over the red cups on the table, and stopped to sip one of the purple flowers in the centerpiece. He then headed for the end of the table, where he sipped out of one of the red cups.

His colors were brilliant. We were all transfixed.

Then, suddenly, he stopped hovering and fell to the table. Skye was closest to him. She touched his breast gently. “He's dead!” she said, looking at all of us. “And he was sipping from the glass of lemonade I poured for myself ten minutes ago.”

“Are you feeling all right?” Patrick asked. “Do you want to sit down?”

She brushed him off. “I'm fine. But what just happened?”

Patrick shook his head. “Don't touch anything. I'm going to get someone from the police.”

“That's really not necessary,” Skye started to say. But Patrick was already gone.

Sarah and I looked at each other and the small still bird. I put down my own glass of lemonade. “I don't think we should drink any more lemonade . . .”

Books by Lea Wait

TWISTED THREADS

Â

THREADS OF EVIDENCE

Â

Â

Â

Published by Kensington Publishing Corporation

THREADS OF EVIDENCE

Lea Wait

KENSINGTON PUBLISHING CORP.

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

KILLER LEMONADE

Books by Lea Wait

Title Page

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Acknowledgments

THREAD AND GONE

B

OOKS

BY

L

EA

W

AIT

Copyright Page

Books by Lea Wait

Title Page

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Acknowledgments

THREAD AND GONE

B

OOKS

BY

L

EA

W

AIT

Copyright Page

Chapter 1

Evil enters like a needle, and spreads like an oak tree.

Â

âEthiopian proverb

Â

Â

Â

One black Town Car, one blue Subaru, and a dented red pickup were parked in the driveway of the old Gardener estate. The massive Victorian had been empty ever since Mrs. Gardener, who'd lived there alone after her daughter's death, had herself died back in the early 1990s.

I remembered hearing stories about the ghosts who lived there. My friend Cindy, who was Catholic, had crossed herself every time we passed it. Local kids challenged each other to trick-or-treat there on Halloween to see whoâor whatâwould open the front door.

I'd never heard of a boy or girl brave enough to walk through the wide gates guarding the entrance to the drive, past the large cracked concrete circle that had once been a fountain, to approach the actual door of the house.

When I'd asked Mama about it, she'd just shaken her head. Said some places drew evil or sadness to them. Someone should tear the old place down.

But no one had. And I'd never seen a

FOR SALE

sign there. The house seemed fated to someday collapse in on itself, keeping past secrets within its cracked walls.

FOR SALE

sign there. The house seemed fated to someday collapse in on itself, keeping past secrets within its cracked walls.

A couple of times in my teens I'll admit I'd made use of a broken window in the carriage house, which had its own entrance a little farther down the road. For a few months, that window was an open invitation to the caretaker's apartment, which, while drafty and dank, was equipped with a bed. No caretaker had lived there for a while. Mice and batsâand teenagers in search of privacyâhad made it their own.

After someone replaced that pane, no one was brave enough to break another window.

Today several people were walking through the uncut field of buttercups that had once been a manicured lawn. They were ignoring the blackflies and ticks, which lurked in tall grasses on early-June days in Maine, and were pointing at the old house.

I turned my small red Honda into the Winslows' driveway across the street and parked by their barn. During the first weeks I'd been back in Haven Harbor I'd borrowed Gram's car, but having my own wheels was really a necessity. I had to pay calls on the shops and decorators and private customers who'd commissioned work from Mainely Needlepoint, the business I'd taken over from Gram. And I couldn't leave her without a car. She had her own life to live, her own future to plan.

I'd never dreamed of me, Angela Curtis, becoming the director of anything, much less a company that did commissioned needlepoint for decorators and high-end stores. Turned out what I'd learned as an assistant to a private investigator in Arizona could be put to good use in Maine. Although running Mainely Needlepoint had been both a surprise and a challenge, the business was now well on its way to paying its debts. So far, I'd had no trouble locating the business's customers, despite having inherited a motley and incomplete set of books from both Gram and my predecessor, the agent who'd driven the business into financial trouble.

That agent was gone, swallows had returned from their winters down south and were refurbishing their nests under the roof in our barn, and Gram was busy planning her wedding to Reverend Tom.

They'd set the last Saturday in June as their wedding dateâonly three weeks off. Gram and I had spent a day at the Maine Mall in South Portland and found her a pale blue silk dress and jacket to wear for the ceremony. I hadn't yet found a dress suitable to wear for my role as maid of honor, but I wasn't panicked. After all, I had three weeks to shop.

I picked up the package I was delivering to Captain Ob and his wife, Anna, glancing over one more time at the Gardener estate.

Without thinking, I touched the small gold angel on the necklace Mama'd given me for my First Communion. “To keep you safe,” she'd said.

Since her funeral I'd worn it every day. Maybe for reassurance? Maybe to remind me no place was truly safe?

Mama, I'm okay. I'm home. Life is good.

Mama, I'm okay. I'm home. Life is good.

I took another look at the people across the street.

Whatever was happening there, I'd hear about it soon enough.

When anything changes in a small town like Haven Harbor, word gets around fast.

Chapter 2

Nothing is so sure as Death and

Â

Nothing is so uncertain as the

Â

Time when I may be to [

sic

] old to Live,

Â

But I can never be to [

sic

] young to Die.

Â

I will live every hour as if I was to die the next.

Â

Nothing is so uncertain as the

Â

Time when I may be to [

sic

] old to Live,

Â

But I can never be to [

sic

] young to Die.

Â

I will live every hour as if I was to die the next.

Â

âEmbroidered on a sampler by Lydia Draper, age thirteen, born December 6, 1729

Â

Â

Â

Anna answered my knock. Through the open door I could see Ob sitting at his computer in the kitchen.

“Good to see you, Angie,” said Anna. Her long, dark hair streaked with gray was pinned up against the seventy-degree heat, and she was wearing faded jeans and a T-shirt. It was a basic outfit for anyone over the age of three. Anna was over fifty. She eyed the package I was carrying. “Is that the needlework kit I ordered?”

“It is,” I said. “Gram says you're one of the fastest learners in her class.” I glanced into the package, to be sure I'd picked up the right one. “You ordered a marked canvas with symbols of Maine, right?”

“I did,” she answered. “It was a patchwork picture. Maine, a lighthouse, a lobster, the date we separated from Massachusetts, a chickadee. Everything Maine.”

I handed it over. “Have fun with it. Gram said to call or stop in if you had any questions or problems.”

I might be the director of Mainely Needlepoint, but I was still in the early stages of learning the craft myself. Anna Winslow had picked it up enthusiastically. I suspected she spent a lot more time with her needle than I did. “And, Ob . . . ?”

Her husband, an experienced needlepointer himself, waved at me in acknowledgment and got up slowly to join us. His back must be bothering him again.

“Here's a check for the wall hangings you stitched this spring.”

He grinned as he accepted it. “Always like a check coming in. I was just updating my website.”

“For your fishing charter?”

“Reservations are down a mite this year. Still too early to predict how the season'll be, though. Some folks don't plan their vacations till the last minute. This summer I'm cutting the price for children aged eight to twelve. Seven hours of deep-sea fishing is a long day on the water for young'uns, and they need help, but I have Josh and a couple of college boys to help me. If we encourage families to come on board, it'll be good for the future of the business. Get kids interested in fishing when they're young, they're customers for life.”

“I hope Josh is more help to you on the boat than he is to me around the house,” put in Anna. “Takes me more time to remind him of his chores than it would to do them myself.”

“He'll be fine,” Ob said. “I'm looking forward to having him with me on the

Anna Mae.

”

Anna Mae.

”

Anna rolled her eyes.

“Makes sense to me,” I said. “Sure you don't want to take on any needlework projects this summer, Ob?”

He shook his head. “Can't be bothered now. If the charters don't pick up, I might be calling you, though.”

I glanced out their front window. “I noticed cars and a pickup over at the Gardener estate. Don't remember ever seeing anyone over there before.”

“Exciting, isn't it?” Anna said. “Word is the place has finally been sold.”

“

Sold?

I hope to someone who has lots of money for repairs. Or who's going to tear it down,” I said.

Sold?

I hope to someone who has lots of money for repairs. Or who's going to tear it down,” I said.

“Jed Fitch's their real estate agent. He said the purchaser's name is being kept quiet until the papers are signed tomorrow. Whoever it is, they're planning to fix it up,” Ob said. “We've waited a long time for this day.”

Anna sniffed a bit. “That crazy old place has been there too long, so far as I'm concerned. It's an eyesore. I hope those new folks burn it to the ground and start over.”

“Now, Anna, you hush,” Ob said. “It was a beautiful house in its day. It would be a feather in Haven Harbor's cap if someone could restore it to what it once was.”

“How did you happen to talk with the real estate agent?” I asked.

“He came to me for the key,” Ob said. “I've been the caretaker there, at least when I was paid, for over forty years now.”

“I didn't know that,” I said, immediately thinking of that broken window. “So you knew Mrs. Gardener.”

“He surely did. That woman was a pain in your âsit-down,' and that's the truth. Just because she had more money than the rest of us, thought she could order Ob around as it suited her.”

“Anna, she was an old woman when you knew herâan old woman who lived by herself. She needed help with the place. She was always good to me.”

“Good?”

Anna sniffed. “Paid you close to nothing, and kept you on call, day and night.”

Anna sniffed. “Paid you close to nothing, and kept you on call, day and night.”

“You lived close enough,” I said, looking out their living-room window. The roof and turrets of the Gardener place rose above the stone wall surrounding their property.

“He used to live closer still,” said Anna. “Used to live right over there, in the carriage house.”

“You did?” I said, turning to Ob and envisioning

that

mattressâOb's mattressâin the carriage house.

that

mattressâOb's mattressâin the carriage house.

“Moved in there after my folks died, when I was a teenager. Did errands for Mrs. Gardener after school and weekends. Picked up her groceries and mail and mowed the lawns and such. She insisted I get my high-school diploma. But after that, I worked for her full-time. When Anna and I got married”âhe threw her a sly glanceâ “Anna wasn't comfortable staying so close to Mrs. Gardener. Living somewhere with the history that place has. I'd saved up a bit by then, since Mrs. Gardener never charged me rent, and she made us a wedding gift of the down payment.”

“Right across the street,” I added. “Giving you the down payment was generous.”

He shrugged. “She and I got along. And being just across the street, I'd still be close enough so I could keep an eye on what happened there. After Mrs. Gardener died, I kept walking through the house and carriage house once every month or two. If repairs were needed, I called New York and Mr. Gardener's lawyer would send up a check to cover my time and materials. Mr. Gardener never came up from New York after Jasmine died, even though his wife was living here, but he kept paying the bills. My salary stopped when he died, about ten years back. I still check on the place once in a while on my own conscience, but now it's in serious need of repairs. At first, I called the Gardeners' lawyer in New York, but he didn't seem to care, and wouldn't pay me to do the work. Wasn't my responsibility to take that on for free. I'm glad somebody's finally taking an interest in the old place.”

“Old rubbish heap, if you ask me,” put in Anna. “Just sitting over there, decaying more every year.”

“I wonder who's buying it?” I asked. “Someone local? Or someone from away?”

“I can't think of anyone local who'd have the interest and the money,” Anna said. “All we know is Jed said it was someone from California.” She paused. “No doubt someone with money. Someone new to lord it over us locals.”

“Funny the name of the buyer is being kept quiet. Who would any of us know in California, anyway? Be interesting to see what the new folks plan to do with the place. It isn't decent for living now.” Ob looked past me, through the window, to where the old house stood.

“We'll have to wait and see,” Anna said, nodding. “I still think they should burn it down and use the land for something practical. A farm. Or a couple of new modern-type houses. After all, Jasmine Gardener died in 1970. Long enough ago for people to forget what happened there.”

“Murder isn't exactly something people forget,” Ob put in, speaking quietly.

“She was murdered?” I asked. “I remember hearing that rumor when I was a kid, but other people said she'd drowned. That it was an accident.”

Ob shrugged. “Some said that. Mrs. Gardener was convinced otherwise. That's why she never left Aurora after Jasmine died. Kept saying she wasn't going to die until she'd figured out who'd killed her daughter. Couldn't accept that death's as unpredictable as life.”

I shivered a bit. “She was only seventeen, wasn't she? Jasmine, I mean.”

Ob nodded. “Seventeen. Had big blue eyes and that shiny, long, straight hair girls had in those days. I always thought she looked like one of my sister's dolls that was too good to play with. Too perfect to dirty up.”

“So you knew her?” I asked.

“I was ten when she died. But, yes, I remember her. My folks knew the Gardeners, and Jasmine was hard to forget.” He shook his head. “It was real sad when she died. Nothing was the same after that. Not at Aurora, anyway.”

“I'd forgotten they called the place âAurora.'”

“When the original Gardeners built that cottage, back in the 1890s, it was the fashion to name summer places. Some folks still do it, but not many. Anyway, story was the first Mrs. Gardener to live there loved to see the sun rise over the hills, east of town.” Ob pointed. “She named it Aurora after the goddess of the dawn.” He paused. “Pretty highfalutin', but they were from New York City, after all. A marble statue of the goddess Aurora, all naked except for her cape, stood in the middle of the fountain, right in the center of the front drive. Looked spiffy, all right, when that fountain was working.”

“They tore the fountain down,” I said, remembering the story.

“Mrs. Gardener said she couldn't stand to look out her window and see the place her daughter died. She hired men in town to break up the statue with sledgehammers and cart away the pieces.” He shook his head. “I was too young to be a part of all that, but I remember my father coming home and telling my mother and my sister, Rose, and me. He was worried about Mrs. Gardener thenâafraid she was going out of her head. But her mind was fine, so far as I could tell. She was stubborn, though. Didn't believe Jasmine had fallen and hit her head and drowned in the fountain. It made no sense to her. Years after that, when I knew her pretty well, she spent all her time thinking of what else could have happened. Talked about it all the time. That's about all she did, in fact. That and”âhe pointed at the needlepoint kit his wife was holdingâ “doing needlepoint. The woman always had a needle and yarns in her hands.”

“It's a sad story,” I said, looking out the window as the red pickup pulled out of Aurora's driveway. “But maybe it will have a happy ending. Maybe whoever bought the house will fix it up the way it used to be.”

“They may try,” said Ob. “With enough money they might be able to bring back the house. But they'll never bring back Jasmine.”

Other books

The Gigolo by King, Isabella

Thorn in My Side by Karin Slaughter

Fenris, El elfo by Laura Gallego García

River of Lost Bears by Erin Hunter

DARK PARADISE - A Political Romantic Suspense by Renshaw, Winter

Depths by Mankell Henning

Color Song (A Passion Blue Novel) by Strauss, Victoria

The Coincidence 03 The Destiny of Violet and Luke ARC by Jessica Sorensen

Saturday Night Widows by Becky Aikman

Murder in Cottage #6 (Liz Lucas Cozy Mystery Series Book 1) by Dianne Harman