Throw Them All Out (8 page)

Read Throw Them All Out Online

Authors: Peter Schweizer

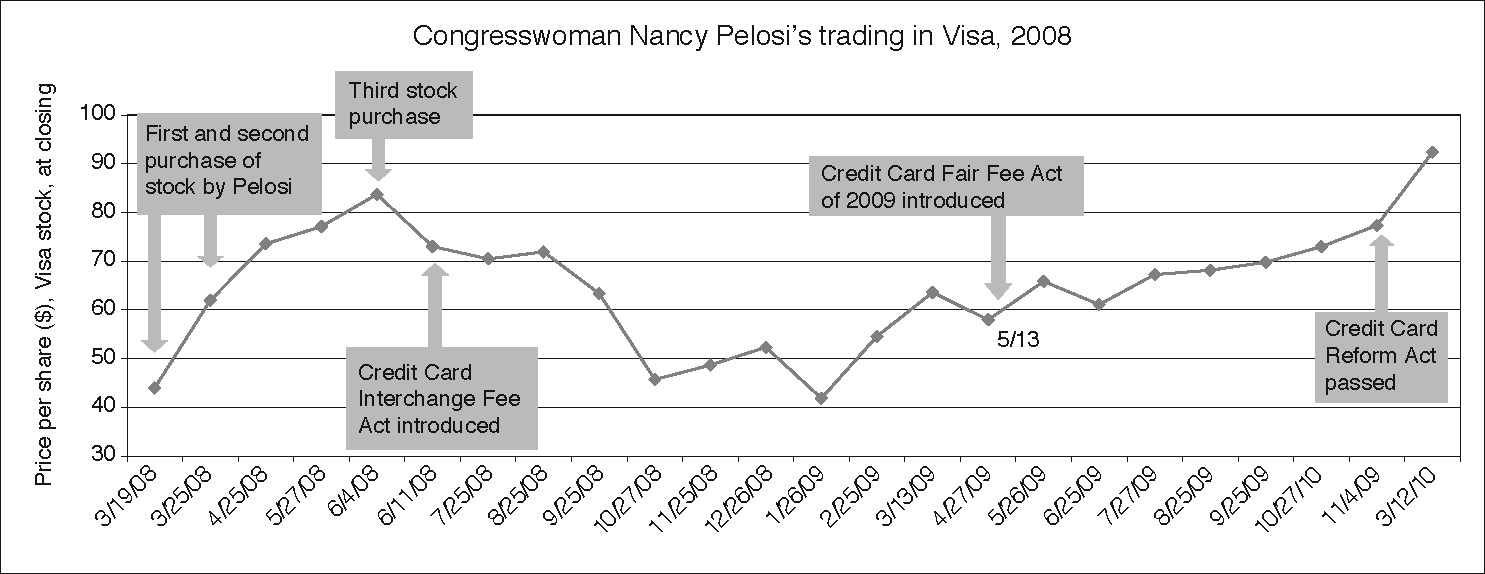

The following year, both bills were reintroduced. Conyers's bill, now called the Credit Card Fair Fee Act of 2009, had even more support this time, including among conservative Republicans like Joe Barton of Texas and liberals like Zoe Lofgren of California. Welch reintroduced his bill as well. Yet again, neither made it to the House floor.

To be sure, Speaker Pelosi did champion a credit card reform bill, one that did become law, but it focused on interest rates charged by the banks. The Credit Card Reform Act provided consumers more information about credit card fees and prevented the issuers of credit cards from jacking up rates. Pelosi declared, on November 4, 2009, that the Credit Card Reform Act was a great victory. "Today, the House voted overwhelmingly to send a strong and clear message to credit card companies; we will hold you accountable for your anti-consumer practices," she said.

8

None of this affected Visa, however, only its client banks. Interchange fees were not touched, though the bill contained a vague clause stating that the issue should be "studied." Little surprise, then, that Visa stock went up when the bill passed. Having squelched legislative action on interchange fees for more than two years, Speaker Pelosi and her husband saw their Visa stock climb in value. The IPO shares they had purchased soared by 203% from where they began, while the stock market as a whole was down 15% during the same period. Isn't crony capitalism beautiful?

Congress did eventually act to deal with credit card swipe fees. But Speaker of the House Pelosi had little to do with it. The Frank-Dodd Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act included a clause that required the Federal Reserve Bank to study and take action on the matter. Pelosi was pushed by her colleagues to support these efforts, but remained outside the fray.

9

All too often we think of corporate interests in terms of campaign contributions or lobbyists. There is a more direct path for corporations and executives to advance their interests: help politicians get rich.

Companies recognize the importance of having friends in powerful places, and granting them access to an IPO is one way to reward them. Members of Congress often participate in IPOs that are difficult, if not close to impossible, for ordinary Americans to join. Pelosi and her husband have been involved in no less than

ten

lucrative IPOs during her congressional career. Not all IPOs, of course, are beyond the public's reach. And some are available by auction, theoretically making them accessible to everyone (assuming your broker is handling the auction). Still, the Pelosis' track record for IPO participation is impressive. These transactions have played a role in making the Pelosis wealthy.

PROTECTING OUR INVESTMENT

Â

Â

Often the Pelosis received stock in an IPO and then sold it days later for a huge profit. In 1993, they bought IPO shares in Gupta, a high-tech company. After the price soared 88%, they sold it the next day. They did the same when they participated in IPOs involving Netscape and UUNet, both of which doubled in value the same day. They also gained access to other oversubscribed IPOs, including those of Remedy Corporate, Opal, Legato Systems, and Act Networks. They sold all of them within a month or two for hefty profits.

The Pelosis may well have participated in even more IPOs, but Nancy Pelosi's financial disclosure forms often obscure dates on which they bought stocks. In December 1999, for example, they bought between $250,000 and $500,000 worth of stock in a high-tech company called OnDisplay. The Pelosis don't tell you exactly

when

they got the shares; they simply list "2X various dates" for the transactions on the congresswoman's disclosure form. OnDisplay went public in mid-December of that year, so the purchases must have happened in that month. And the investment worked out very well.

Months later,

OnDisplay was bought out by Vignette, and the Pelosis made up to $1 million in capital gains. Interestingly, Vignette's IPO was underwritten by William Hambrecht, an investment banker, a longtime friend of Nancy Pelosi's, and a major campaign contributor.

A few years later, the same Bill Hambrecht went before the House Finance Committee, chaired by Barney Frank, a Pelosi ally, to push for a change in the registration process for stock IPOs, an exemption called Regulation A. Under current law, a company that plans an IPO of less than $5 million in stock gets an exemption from detailed reporting. Hambrecht wanted the exemption raised to $30 million, which would greatly benefit his business, making IPOs easier, quicker, and far less expensive. As the hearings began, Congressman Frank said, "I should note also that it was Speaker Pelosi who first called this to our attention earlier in the year. It is something that the speaker has taken a great interest in because of her interest in job creation, so we have had to find a way to have this hearing."

10

Indeed!

Â

Pelosi is not alone in benefiting from IPOs. Other lawmakers have profited from public offerings issued by companies and entities interested in currying favor in Washington. Senator Robert Torricelli, for example, made $70,000 in one day, courtesy of a New Jersey bank's IPO. In 1997 alone, Torricelli was involved in no fewer than nine stock IPOs. Senator Jeff Bingaman enjoyed a 378% return on his investment in Avanex after just one day of trading. Senator Barbara Boxer reaped rich returns after she was given the chance to participate in IPOs involving Avenue A (up 200% the first day) and Interwave Communications (up 184%).

11

There are no doubt many other lawmakers who have participated in IPOs, but they are not required to designate their stock transactions as such. And it is extremely difficult to track IPO transactions given to politicians.

Congressman Gary Ackerman was given access to stock in a private companyâand he didn't even need to use his own money to make a large profit. Ackerman, who sits on the Financial Services Committee, had the opportunity in 2002 to buy private shares in a company called Xenonics, which makes military-related technologies. The investment didn't cost Ackerman one cent. The firm's biggest shareholder, Selig Zises, loaned the congressman $14,000 to buy the stock. "Gary is one of my closest friends," explained Mr. Zises. "I was only happy for Gary to make some money. If the thing succeeded, he paid me back."

12

Ackerman used his position as a congressman, and as a fervent supporter of Israel, to arrange a meeting between Xenonics executives and Israeli officials to discuss a deal involving the company's night-vision systems. After the company went public in 2005, Ackerman was able to sell his shares for more than $100,000.

13

Did Ackerman do anything wrong? Most of us would say yes! But experts say that based on current rules, the only thing he did wrong was not have a written agreement covering the loan. Otherwise, it was all aboveboardâat least according to House ethics rules. Think of it: you can get IPO shares in a company, buy them with money from a friend, make lots of money, and your only mistake is not writing the loan down on paper.

14

Other members of Congress could be singled out too. But Nancy Pelosi stands out for two reasons: not only is she enormously wealthy, and thus (like John Kerry) able to invest in large amounts, she is also one of the highest-ranking members of the House. There are many companies that want to curry favor with the Speaker or majority leader of the House of Representatives.

One of the IPOs that the Pelosis participated in was Clean Energy Fuels, in which they landed up to $100,000 of stock. The company was founded by Texas billionaire T. Boone Pickens, who wanted to promote the use of liquid natural gas as a solution to America's dependence on foreign energy. In other words, the company was hoping to exploit America's vast natural gas reserves while reducing our dependence on petroleum. Arguably, that's a fine goal. As the

Wall Street Journal

noted at the time, expanding natural gas was a key plank of the Democratic Party's energy platform.

15

What isn't so fine is that the Pelosis now had a financial stake in the issue. As Speaker, Nancy Pelosi pushed a series of bills that would benefit Clean Energy Fuels. The stock did well. The Pelosis got it at around $12 a share. By April 2010, it was trading at more than $20 a share.

The Pelosis' investment in natural gas did not end there. In November 2007, they participated in yet another IPO, this one involving Quest Energy Partners. They bought up to $500,000 in what was described by investment advisers as "a company that exploits and develops natural gas properties." (This IPO was handled by Wachovia Securities.)

16

Pelosi became a champion of natural gas, pushing for tax benefits as well as aggressively backing global warming legislation that would tax carbon emissions. Natural gas would benefit enormously if any of these bills became law. Pelosi went so far as to state on

Meet the Press,

"I believe in natural gas as a clean, cheap alternative to fossil fuels." (Of course, natural gas

is

a fossil fuel.) There is nothing wrong with a policy decision to reduce our dependence on foreign oil. But there is something wrong when the policymaker has a financial stake in the game.

In 2008, Clean Energy Fuels also backed California Proposition 10, a ballot initiative that would require the state to float a $5 billion bond offering to subsidize the purchase of "alternative fuel" vehicles. Clean Energy Fuels donated at least $3.2 million to the ballot campaign. Nancy Pelosi endorsed the initiative.

In corporate America this would be a clear conflict of interest. Persuading a corporation to spend money on an initiative that you as an executive would personally profit from would raise huge questions. And if you were a middle-level employee in the executive branch of government, such a conflict of interest would trigger an investigation. Trying to help companies in which you have a large financial stake become more profitable through congressional legislation

is the very definition of conflict of interest.

But Pelosi tried to turn what was a vice for most everyone else into a virtue. "I'm investing in something I believe in," she told

Meet the Press

host Tom Brokaw. "I believe in natural gas as a clean, cheap alternative to fossil fuel." But, of course, she was also investing in something she could make more profitable by changing government policy. When Brokaw asked her that very question, she responded, "That's the marketplace."

17

But it's a marketplace where politicians get to set the terms and the rules and influence the outcome. Accumulating wealth or growing the wealth you already have is much easier when you have a piece of the action.

R

ECALL THE STORY

that opened this book, of Dennis Hastert's $10 million gain during his speakership. Unlike many of his colleagues, Hastert was never much of a stock trader. So how exactly did he do it?

By following George Washington Plunkitt's lead, in the form of a land deal. For Plunkitt, this entailed buying up land that he knew the government would need to purchase in the not too distant future and then selling it to the government for a healthy profit. Today, such a blatant move would appear too crude. Yet the land deal survives in disguised form. The Permanent Political Class has become more sophisticated in how it enriches itself by mixing real estate investments with taxpayer money. It is completely legal. Indeed, congressional ethics committees have even deemed it "ethical." And land deals are easier to camouflage than stock transactions. You can be fuzzy about the location of the property, and since there is no set price for the land, as there is for shares of stock, you can mask your profits more easily.

Â

In 2002, Hastert bought a 195-acre farm on Little Rock Creek, in Kendall County, Illinois. He purchased it in July, just before the state's transportation secretary, Kirk Brown, approved the design of a land corridor for a road called the Prairie Parkway, on July 31. The farm was just 2.4 miles from the parkway corridor and 5 miles from the nearest proposed highway interchange. In February 2004, Hastert and two partners made a second land purchase. They formed a trust and bought another 69 acres right by the interchange in Plano, Illinois. They paid $15,000 an acre. Hastert reported this on his financial disclosure form, but his name does not appear on real estate records. Instead, Kendall County public records show that a Little Rock Trust #225 acquired the property. On his disclosure form, Hastert listed the investment simply as "¼ share in 69 acres (Plano, IL.)," giving no address or parcel number, as he is required to do by House rules.

Plano is smack dab in the middle of farm country. It is the birthplace of the mechanical reaper. It boasts a population of about 5,000. It's also the town where Hastert has maintained his residence. As farmland those 69 acres were of some value. But as a possible residential site, where the land could be split up and developed, the sky was the limit. And that's what was intended: the Robert Arthur Land Company, through an entity called RALC Plano, was developing a residential community called North County, which would include more than 1,600 acres of land (including Hastert's acreage) as well as 33 acres of commercial enterprises and retail shops. In addition, 18 acres were set aside for a public school.