Trapper Boy (4 page)

Authors: Hugh R. MacDonald

Chapter 9

J

uly was almost over, and JW's bedroom wall was filling with pictures of the underground workings of the mine. The details of how each part fit with the others in order to ensure safe production of coal were interesting, but JW missed the stories of talking fish and runaway horses and the bones of long-dead animals. But it seemed important to his father that he pay close attention, so he did.

He learned that hard coal, mined in Pennsylvania, was called anthracite and was used largely in homes for heating. He also learned that softer coal, the kind mined in Cape Breton, was known as bituminous. Since there was no known anthracite in Nova Scotia, bituminous was what they used as fuel in their homes. Bituminous was also used in the production of coke and coke was used in the production of steel.

As he put the pictures together on his wall, JW noticed they were forming a mural. It looked like an underground city with men whose blackened faces had a haunted look. Some leading and others following horses along the railway lines. He shivered as he peered into their faces. His eyes were always drawn first to the one that looked like his friend Mickey.

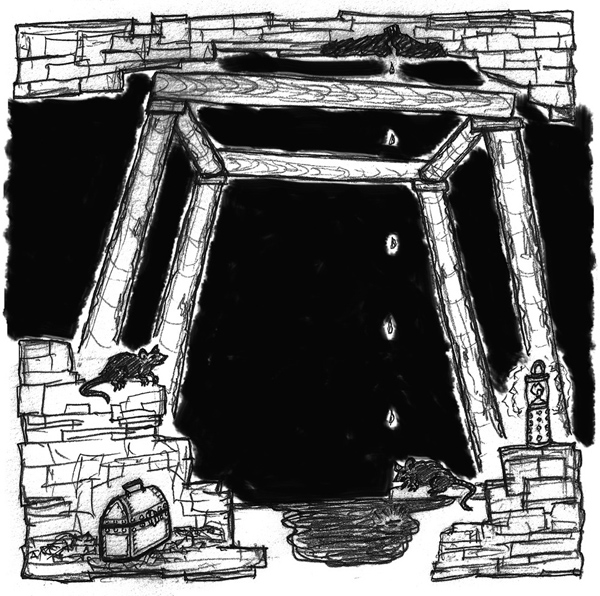

His father hadn't included a picture of the opening where the men went down in the trip to the mine below, but he told him about it. The trip, or rake, as it was also called, consisted of pulley cars that ran on small railway tracks. JW followed the natural progression from start to finish and traced tunnels where men used black powder to blast open new seams of coal, and followed other tunnels that were already in production. Huge timbers had been put in place to support the roof. In other areas, pillars of coal were left to hold up the ceiling overhead. Two-man teams dug out the rooms and loaded the coal. Their backbreaking work expanded the mine deeper into the earth and even under the ocean.

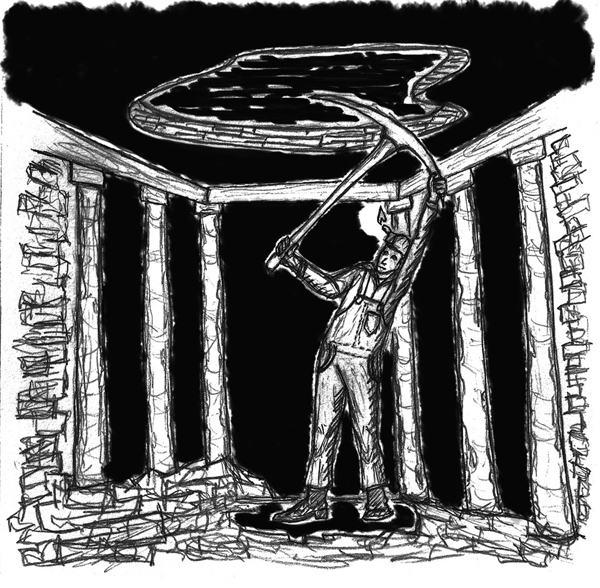

JW was surprised to learn that once a room was stripped of its coal, the ceiling was collapsed using a pick. The resulting mass of coal was known as a miner's harvest. It was extremely dangerous work and could be fatal. Only the skill of the miner and his wits kept him safe. The harvest was part of his own father's work. Fear entered into JW's heart for his father and for his friend Mickey.

His father stressed the importance of the two shafts that were constructed along the seam of coal. One shaft carried fresh air into the deeps, which was the working face of the mine, and the other shaft carried the stale, gas-filled air back to the surface. JW learned that canaries, housed in little cages carried on a pole, were used as a warning system to let the men know when the gas levels were dangerously high. If the canaries jumped about or died, then the men knew it was time to leave the area. He learned more than he ever wanted to know, but his father was relentless in his instruction. He told him that a building on the surface housed the fans that blew the air into the mines. He learned that years ago there were furnaces used in the mines to circulate the air, but they were too dangerous and increased the risk of explosions. They were replaced with the fans.

“See here? This is where they extended the mine. The old shaft had to be boarded up to keep the air in. You see there? That's where they cut a hole and put a door so the horses can get through. They call it a trap, a trap door. You open the door to let the horse through, then you close it quickly to trap the air, to keep it from crossing over so it'll be forced down to where the men are working. That's where they came up with the name, trap boy or trapper boy. You understand?” his father asked.

“Sure, Da, I understand,” JW said. “But I never plan to go down there.”

“John Wallaceâ” his mother began, but stopped as she caught her husband's look. She saw him shake his head

no

. “Why don't you finish up your breakfast and go fishing for the day? I'm sure Beth will be by soon.”

“We're going to go to the fort and read for the day. I still have two whole books left and half of another one to read before school starts back. It's hard to believe summer's half over. If they teach any courses on coal mining, I'll know most of it. Same time tomorrow, Da?” JW asked.

“Same time. Maybe I'll have a funny story to add. We'll see how tonight goes. How's that sound?”

“Just as long as there's pictures,” JW said as he left the kitchen table. “See you at supper time.” He hurried out the back door and across the field. He wanted to get there before Beth.

Chapter 10

“W

hy do you figure he's telling you all the stuff about the pit?” Beth asked.

“I don't know, but I don't like the sound of it,” JW said as he leaned against the wall of the fort,

The Count of Monte Cristo

propped up on his knees. “It's probably because I've asked for so many stories over the years and now I'm getting older, so he's telling me grown-up stories. It makes me worry for my father and poor Mickey. I just couldn't imagine doing that for the rest of my life.”

Changing the subject, JW asked, “What did you bring for lunch?”

“Me? I thought it was your turn to bring lunch,” Beth said. “Just kidding.” She laughed as she pulled a drumstick for each of them from the basket.

JW could see other goodies in the picnic basket and thanked her as she handed him the food. Finally, when he'd finished the large slab of apple pie, he didn't think he'd be able to move for an hour. Gulliver had fared well also, eating the leftover scraps of chicken.

Beth and JW discussed the first two chapters of

The Count of Monte Cristo

and agreed that it was a great story to get lost in, whisked off to a fanciful time.

Chapter 11

JW

listened as his father spoke of the importance of understanding the workings underground. It was mid-August, and although the pictures had stopped, the stories of the pit had intensified. Stories were repeated over and over, and JW was sometimes asked to bring the pictures to the table so his father could point out locations where each job was carried out.

He learned the history of mining, at least the recent history, and how there was a brotherhood among the men who worked underground and how sticking together was crucial to the success of the union.

“Sometimes we hafta to go on strike in order to get better wages and better working conditions,” his father said. “Last year's strike took a terrible toll on the men. William Davis lost his life for the cause, being shot by the company goons. There's talk a strike could be just as bad again this year. Roy the Wolf wants to take more from the little wages we're getting now. The Company could end up closing with him at the helm.

“If it hadn't been for our union leaders, especially J. B. McLachlan, fighting for our rights, we'd be working for nothing. He had us stand up to Wolvin last year. It even cost J. B. four months in prison on some trumped-up charge. Wolvin only cares about money. If we don't agree to his terms, he just cuts our hours even more. With the shifts cut to three or four a week, I can't make it on the little that's coming in now, JW.” Andrew Donaldson looked into his son's eyes and then looked at his teacup.

“Maybe I can get a part-time job after school, Da. I could check down at the Co-op, see if there's anything there with deliveries after school and on Saturday.”

“Mr. Ferneyhough's got two boys working there now, and I heard that a few miners have even approached him looking for work. Before long, with the hours cut back, Mr. Ferneyhough's not going to be very busy either. I wish there was something you could do after school.”

“Maybe I could help some people with their gardens?”

“I'm sorry, JW. You hafta go to work. We don't have any other way to get by. I talked to the manager and he said you can start underground as a trapper boy 'cause they don't need any more boys picking rocks at the breakers. It's better pay anyway.” Andrew stood up from the table and began to walk outside.

“What? You want me to go in the pit? I'm going to school. I can't go to work there!” JW shouted.

“There won't be any school, John Wallace. Weren't you listening? We've got no choice. My hours have been cut, and if we can't pay the taxes on the house, we'll lose it. The government will take it. Besides, I owe the Co-op most of my pay, and I can't keep running up a bill if I can't pay it.”

“It's not fair! I shouldn't have to go in the mines.”

“Life's not fair!” His father stared at him. “I pass by lots of boys every day that work at the breakers and others working underground, including Mickey.” His father's voice softened. “I wish it wasn't so, but it's all set. You start in two weeks,” he said, then went outside.

“We're sorry about your schooling, John Wallace, but we need the money,” his mother said.

No school and stuck in the mines forever. He felt betrayed. He rose from the table.

“You can do whatever you want for the next two weeks.”

JW gathered the pictures together and moved slowly as he walked upstairs to his room. He laid the pictures on his bookshelf, no longer interested in putting them on the wall, for all too soon he'd be able to see himself alongside Mickey. Tears streamed down his face, and he was overcome by a mix of anger and frustration. He wanted to go to school. He wanted to visit far-off lands.

He lay face down on his bed to smother the sound of his crying and didn't hear his mother come into his room. He felt her hand rest on his back.

“I'm sorry, John Wallace. I know you had your heart set on school. Maybe in a year or two the wages will pick up and you can go back then,” she said in a reassuring voice. “Right now your father is working every available hour, and we can't keep up.”

“I know, Ma, but once I'm in, I'm there for good,” he said. A sudden thought came to mind. “Will I be working the back shift like Da? Maybe I can still go to school and sleep in the afternoon.” Sitting up in his bed, he said, “Yeah, that's what I'll do. If all I gotta do is pull the door open and closed all night, then I should be able to go to school too.”

JW didn't see the sad look in his mother's eyes as she said, “Well, you can sure give it a try. Why don't you go fishing for the day, or go see Beth?”

“I think I'm just gonna lie here for a while and think about things. Tell Da I'll talk to him later,” was the quiet reply.

Chapter 12

“I

didn't have the heart to tell him he'd be too tired to go to school after working all night. I don't see the harm in letting him think he'll be able to do it,” Mary said. “He seemed to perk up once he figured he could do both.”

Andrew rubbed his calloused hands over his face. “Not much chance of that. The poor little fella. He doesn't know the half of it. It's a different life down there. You stop being a boy the minute you go underground. He'll be treated like one of the men, and there's no place for fear of the dark.”

Andrew and Mary walked arm in arm toward the barn, each one silently wishing that life was fairer and that JW could remain a child for at least a little while longer. They walked behind the barn and saw the garden. The plants had grown well under their son's care.

“There should be enough potatoes to last the winter,” Andrew said. “He worked hard on the weeding. Well, I better get in and get to bed, though I don't think I'll sleep much.”

“I told him he could have the next two weeks to do as he pleased,” Mary said. They looked at each other and fell silent.