Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (23 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

‘He was unrighteous,’ said Billiard-Fanon in a resonant voice, nodding as if this information confirmed everything he has said. ‘His spirit cannot find rest!’

‘How did you know it was him?’ asked Castor.

‘It was him,’ said Capot. ‘I recognised him at once. The wound was in his head, where you shot him, Ensign. When he opened his mouth to speak, blood poured out like a scarf of scarlet. His beard was ruby and glistening with the blood. He was wet, all wet with blood.’

‘His spirit bears the stain of the innocent blood of others that he spilled!’

‘Then he spoke to me.’ Capot shuddered, his skin like a horse’s flank twitching under the irritation of midges.

‘What did he

say

, lad?’ asked Billiard-Fanon, not unkindly.

‘He said we should all get out. He said a monster was coming greater than the most terrible of earthly leviathans. He said we must all get out.’

Billiard-Fanon’s authority was sealed by this apparition. Capot was convinced that they were facing a spiritual test; Pannier, his voice slurred now with drink, swore that he would follow the ensign ‘to the ends of the earth – or the ends of this endless ocean, if needs be.’

‘You’d follow anyone who gives you a drink,’ cried Le Petomain, moving his bruised jaw gingerly from side to side. ‘Castor! You must see – he is insane!’

‘I’m an engineer,’ was Castor’s reply. ‘I believe in the laws that make machines work. But we’ve seen some things … we’ve all seen some things aboard this vessel that science cannot explain. I say – well, I say Billiard-Fanon’s explanation makes the greatest sense of any I have heard.’

‘Makes sense?’ snapped Le Petomain. ‘What sense?’

‘The ghost, Monsieur?’ Castor pressed. ‘The poltergeist who keeps throwing our belongings about? The sea-devils outside? You cannot explain all this in material terms.’

Billiard-Fanon spoke up: ‘You were so kind as to suggest I should be confined to my cabin,’ he said. ‘Well, I am now in a position to return the favour. Capot, Castor – take him off.’

‘And I, Monsieur?’ demanded Jhutti, straightening his back, and speaking with as much dignity as he could muster. ‘Will you kill me too, because I happen not to worship the same gods you worship?’

Billiard-Fanon put his head on one side. ‘The taciturn Indian,’

he said. ‘What to do with you? Well, nobody is beyond God’s grace, Monsieur. I suggest you too spend a little time in your cabin, like a monk in his cell. I suggest you contemplate the nature of the threat we all face.’

Capot took hold of Le Petomain’s elbow, but the pilot shook himself free. ‘You’ve killed us all, sailor,’ he said. ‘Giving this madman the pistol – it’s doomed us all.’

‘You

didn’t see him,’ said Capot, in a bleak voice. ‘The ghost. I saw the ghost with my own two eyes. The

Plongeur

is haunted.’

‘We’re all doomed,’ repeated Le Petomain in a low voice. Finally he permitted himself to be led off the bridge, bent double, and away along the aft corridor. Jhutti went too.

Soon enough Capot returned. ‘I looked in on the lieutenant,’ he said. ‘He’s sleeping.’

‘We four will suffice!’ declared Billiard-Fanon, with a gleam in his eye. ‘Four Christian Frenchmen! On us, and our faith, depends the future of this vessel. Prayer, and belief, and the power of Christ are our best protection! Let us pray!’

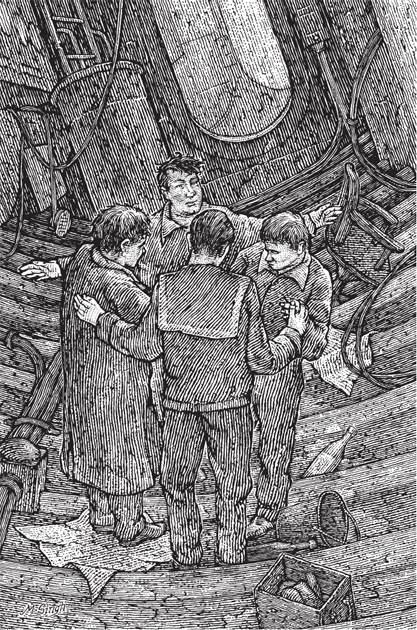

The ensign tucked his pistol into the belt of his trousers. Pannier belched and started to laugh; but when the ensign looked severely upon him his face fell, like a child who has been rebuked. Billiard-Fanon joined hands with Castor on his left and Pannier on his right; Pannier took Capot’s hand, and Capot completed the circle with Billiard-Fanon.

‘Ensign,’ said Capot. ‘I was in the observation chamber with Le Petomain and the Indian, and we saw another of the great underwater lights, shining. Ensign – what

are

the lights?’

Billiard-Fanon answered immediately, with complete conviction. ‘The lights,’ he said, ‘are the light of God shining through into this benighted, devilish ocean. That is why the Satan-fish swarm and school around them in such numbers; they are trying to block out the light. But if we pray hard enough, God will guide this stricken vessel

into

the light, and through that mystic portal we will come home again. We came close before, but we were not then worthy. But we have purged our number of the ungodly since then!’

Capot dropped his gaze; and Pannier looked impressed, in a

drunken kind of way. But Castor retained enough of an engineer’s natural scepticism to ask, ‘How do you know?’

‘Because,’ Billiard-Fanon replied, serenely, ‘God has told me.’

The engineer sucked in his lower lip, and plopped it out again. ‘For real?’

‘He is pleased that we have purged the

Plongeur

of the unrighteous,’ Billiard-Fanon reported. ‘With prayer and supplication we can reach him – He is speaking to me, right now, and He tells me so. Do everything I tell you to do and He may still save us!’

Young Capot shut his eyes, and his face assumed a fervent expression. ‘I believe!’ he announced.

‘Sure,’ agreed Pannier. ‘The spirit is moving within me, whatever.’

‘Let us pray!’ said Billiard-Fanon. And as he began, the others mumblingly joined on, ‘Our father, who art in heaven …’

Le Petomain sat with his back against the surface that had once been the floor of his cabin and rubbed his face. He worked his jaw around the tender spot where it connected to his skull, just underneath his ear. ‘The world has gone mad,’ he muttered to himself.

Time passed. It was impossible to gauge how long. The metal fabric of the submarine creaked intermittently, and the descent continued without abatement. At one point Le Petomain heard the sound of hymn-singing, muffled to incoherence by the intervening walls.

He waited as patiently as he could. ‘This,’ he told himself, ‘will not end well.’ His stomach growled hungrily, but he knew there was nothing he could do about that.

After a while, the door was opened and Pannier was there. ‘The holy one wants to see you,’ he announced.

‘The holy one?’

Pannier grimaced, as if to acknowledge the absurdity of it. But what he said was, ‘He’s taking it

very

seriously, I should warn you. Don’t mock him. And young Capot is a true believer. Seeing that ghost has turned his head.’

‘And you, Herluin? Are you a true believer?’

‘I believe prayer is as likely to do as any good as anything else – more so than engineering. To tell you the truth: I believe we’ll all be dead in a few days whatever we do. And I tell you what else.’ He grinned. ‘The holy one actively encourages the use of wine sacramentally in worship.’

‘The wine is all in the flooded mess, surely?’

‘I’ve a few bottles, squirreled away in other places,’ Pannier admitted. ‘And if it comes to it, I may go for a little recreational diving to recover the rest. We’ve still got one suit left, after all. Anyway – come along. The holy one wants to have a word.’

Pannier led Le Petomain back to the bridge, where Billiard-Fanon was sitting on the side of the rotated-about captain’s chair, like a throne. Capot was squatting beside him, like a faithful hound. ‘Where’s Castor?’ Le Petomain asked.

‘Castor is having another look at the engines,’ Billiard-Fanon replied, in a heightened ‘serene’ voice.

‘I’m pleased to hear he hasn’t been executed as a heretic, at any rate,’ said Le Petomain, sarcastically.

Billiard-Fanon looked at him. ‘I have every reason to believe that Monsieur Castor is a good and faithful servant.’

Le Petomain straightened his spine. ‘I’m supposed to call you the holy one, it seems?’

‘We prayed together, we four. The holy spirit entered into me. Calling me the holy one has nothing to do with my merit, or eminence. It is acknowledging the glory of God. Surely you can see that?’ He lifted the pistol from his lap, took the stock in both hands, and aimed the barrel at Le Petomain’s chest.

‘Shoot,’ said the latter, calmly. ‘Go ahead. We’re all doomed anyway. Might as well get it out of the way.’

‘But we are

not

doomed. There is a road out of death, and into light – and it is me,’ said Billiard-Fanon. ‘Science won’t save us, but faith will.

I

am the shield of faith – the Holy Spirit has vouchsafed to me that it is only my presence upon the

Plongeur

that is keeping the aquatic devils from overwhelming us and feeding upon our very souls.’

‘You may believe what you wish, Monsieur,’ replied Le Petomain, with dignity. ‘It is no concern of mine.’

‘If I asked my disciple here to pull out your tongue,’ said Billiard-Fanon, his voice betraying irritation for the first time. ‘He would.’ He dropped the pistol back into his lap, and patted Capot on his head. ‘But I am merciful, because the Holy Spirit that flows

through

me is merciful.’

‘Look, Jean,’ said Le Petomain, wearily. ‘You can believe what you like. Young Capot, there, and Pannier – that old soak – even Castor, with cogwheels where a human heart should be. All of you! Believe what you like, but leave me out of it. Shoot me, if you wish. Or send me back to my cabin.’

Billiard-Fanon shook his head. ‘I am sorry to hear this,’ he said. ‘You have given up hope. But hope, who is Jesus Christ and Lord of the universe, has not given up

you

. I have been given a vision of how we can return home. Follow me, and provided only that you have enough faith in your heart we will end this day – this very day – back in the harbour at Saint-Nazaire!’

Le Petomain sighed. ‘Jean, I only …’ he began to say.

‘No!’ interrupted Billiard-Fanon. ‘You have a devil of despair inside you. We shall cast him out – because your despair would poison the ceremony.’

‘Ceremony?’

‘God has given me a vision. The world is fourfold, the tetragrammaton! YHWH, the holy name of God – four letters! – the Christian trinity

plus

mankind, folded into the bosom of the divine, three plus one is

four

. I am the holy one, the shield of faith, preserving the vessel from the devils outside. But I am the head. The vision is unambiguous. I must have

four

disciples, all praying in the correct way, for the grace of God to lift us out of this hell.’

‘Capot, Castor and Pannier make three,’ said Le Petomain. ‘I see. So get the lieutenant to be your fourth.’

‘Lieutenant Boucher is … not responsive,’ said Billiard-Fanon. ‘He is not competent to … to be allowed out of his cabin.’

Le Petomain shook his head. ‘Poor fellow,’ he said. ‘Well – what about Jhutti?’

‘A pagan!’ retorted Billiard-Fanon, in a shocked voice. ‘A heathen? Hardly! No, my friend. It must be you. You must be the fourth.’

‘Capot, Castor, Pannier and me – an unlikely group of monks, I must say. So – what? We four say the Lord’s prayer backwards and it magics the

Plongeur

back to port.’

Billiard-Fanon sighed. ‘Such weakness of faith! No wonder God is testing us. Well,

Second-Mate

Annick Le Petomain, known to some as Le Banquier, and erstwhile pilot of this vessel. I am the way, the truth and the light, and I shall help you.’

Pannier’s face appeared suddenly over Le Petomain’s shoulder. The reek of rum was unmistakeable. ‘Happy to assist, holy one,’ he leered, grabbing the pilot’s two elbows and crushing them together behind his back.

‘Sometimes,’ said Billiard-Fanon, getting to his feet and taking hold of the pistol by its barrel, ‘Satan must be chastised with a rod!’

‘It is clear,’ gasped Le Petomain, his arms twisted painfully behind him. ‘That you are insane. Insane!’

‘The madness of faith is a very different thing from the madness of Enlightenment Reason,’ said Billiard-Fanon in a level voice as he raised the pistol. ‘The latter breeds monsters; but the former releases the mind from its material manacles and brings you closer to God.’

The butt of the pistol came down upon Le Petomain’s skull with the sound of somebody knocking at a door.