Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (33 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

‘He knows what was in your brain, I suppose?’

‘Only if he thinks to ask me. He cannot simply flick through my thoughts, as the pages of a book. But he can ask me a question and compel me to answer truthfully. But then he needs to know which questions to ask! For example, he opened the portal—’

‘He

did that?’

‘Of course! And he sent some of his creatures through. But the portal is, of course, into deep water, and on

earth

, unlike here, deep water is severely pressurised. His creatures were pulped to jelly! He has a prodigious intellect, but he simply hadn’t thought

through what conditions would be like in such a – to him – alien environment.’

‘But the crack remained open?’

‘He sealed it. A good thing too! The pressure differential would have resulted in earth’s oceans decanting themselves wholly into this place in only a few years. Perhaps a hundred years passed before I came along in the

Nautilus 2

. I reopened it – how I wish I had not!’

‘What happened to your vessel?’

‘My vessel?’ Dakkar sounded confused.

‘The one in which you travelled here.’

‘I scuttled it, blew it to shreds when I understood the danger the Great Jewel posed. But by then it was too late. He already had my crew – and myself.’

‘So the portal has been open for … fifty years?’

‘Not continuously. It is phased. But, in essence, yes.’

‘Can it be permanently sealed? To lock him out.’

‘Oh, he could open another, if he chose. He tried opening one in land, fifty years ago – in the wilds of Eastern Siberia. But that went wrong – catastrophically wrong. There was a huge explosion.’

‘1908, Siberia …’ Lebret muttered.

‘He is competent with water as a medium; but solid rock is almost incomprehensible to him. Still, that doesn’t mean he couldn’t open another oceanic portal.’

Lebret shook his head. ‘He has the powers of a god.’

‘No, no,’ wheezed Dakkar. ‘He is powerful, but not supernaturally so.’

‘Creating underwater suns!’ Lebret countered. ‘

Fiat lux

!’

‘They are not suns, not in the way familiar from our cosmos,’ said Dakkar. ‘Points of intense light, pushed up from infraspace, to enable the algae to photosynthesis, to make food and oxygen for the creatures. The cores are no more than a few metres across; although, obviously, they are surrounded by a much larger shell of roiling, superheated steam, and beyond that a layer of water tripping on the edge of boiling. Very complex flow patterns, actually.’

‘And these are relatively

recent

inventions of his, I presume?’ Lebret asked.

‘Exactly!’

‘If they were here long enough, I suppose they would eventually boil the water in the entire cosmos!’

Dakkar wheezily laughed. ‘My contempt for your lack of scientific deductive powers was perhaps premature,’ he said. ‘You’re right, of course. Eventually the entire cosmos would turn to steam. It would take a very long time, but it would eventually happen.’

‘But if this cosmos is infinite in extent, as our universe is, then surely it would take an infinite amount of time to heat up?’

‘The cosmos here is infinite in extent, as ours is; but that does not mean it is constituted by an infinite mass of water,’ wheezed Dakkar.

‘I—I don’t follow …’

‘The geometry of infinity folds space-time back on itself. And at any rate, the Jewel is, physically, trillions of kilometres away from where we are, here. It would take hundreds of thousands of years for the heat from these stars he had created to penetrate the medium and reach him.’

‘Trillions?’ gasped Lebret. ‘How can he influence things

here

, when he is so very far away?’

‘Trillions of kilometres describes the geometry of superspace. It is a different logic in infraspace, a dimension in which he has … certain capacities.’

‘“Infraspace”,’ Lebret repeated. ‘“Superspace.” If there is an

under

-space and we inhabit the over-space, then where is … space?’

‘A question as much philosophical as scientific,’ was Dakkar’s opinion. ‘Personally, I incline to the opinion that space is actually a three-dimensional manifold, two spatial modes and one temporal mode of extension. Our four-dimensional bubbles, blown from the actual plane of existence, are anomalies in this larger scheme. But it hardly matters.’

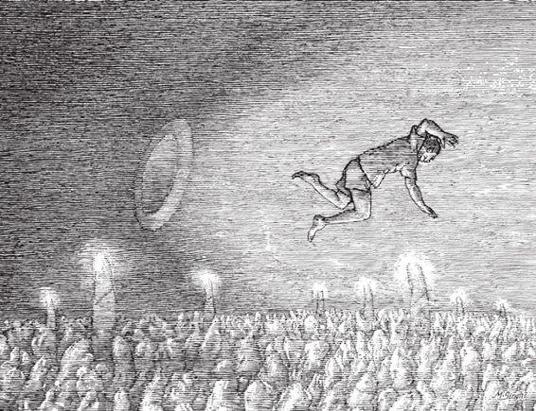

He drifted off, and appeared to be asleep. Lebret ate a few more mallows, and took a drink from the bulb of water. He wondered, idly, what the toiletry arrangements were. A second, leisurely

exploration of the space revealed nothing that looked as though it would serve. Presumably it would be possible to relieve oneself in the water – but as this was also the water he was drinking, he felt inhibited from doing so. In the end he compromised; floated back along the corridor and opened the lid onto the wide expanse of the shell-platform, lowered his body in up to the waist and relieved himself. It was all part of the larger ocean, of course, but this seemed somehow more hygienic.

Coming back below, rubbing beads of water off his naked legs, he found Dakkar awake and staring at him. ‘I wonder,’ he asked the old man, ‘why you have a hatchway up there – but none for the entrance to your second chamber, there.’ He pointed.

‘Because that corridor opens into the ocean. If it had no doorway, like this bulb, why then – unpredictable flows and surges would force water through. This, however, leads through to a sealed chamber.’

Lebret came to sit beside the old man. His freakish dimensions no longer struck him as repulsive; indeed, there was considerable pathos in the pain and weariness of his eyes. ‘I apologise; that was a trivial question. Let me ask a larger one.’

‘Please do.’

‘Monsieur le prince

,’ Lebret asked. ‘Your … message, shall we call it?’

‘Yes?’

‘Did

you

send it? I mean – was it of your own volition? Or was it the Jewel, forcing you to lure human beings down here?’

Dakkar smiled thinly. ‘You have started to demonstrate some impressive powers of scientific deduction. I am confident you can deduce the answer to that question for yourself. I am – tired. I am very tired.’

Lebret slept, and awoke thirsty. His eyeballs felt hot. ‘

Monsieur le prince

,’ he said, as he pulled himself over to the water bubble to drink. ‘I feel unwell. Hot – feverish.’ The words did not form themselves very comprehensibly, and Dakkar, barely opening his right eye, gasped, ‘What did you say?’

Lebret felt the side of his face; it had swollen further. ‘Hot,’ he said, making an effort to enunciate. ‘Feel feverish.’

‘It is likely, Monsieur,’ croaked Dakkar, ‘that the wound in your jaw has become infected. As, perhaps, was inevitable, without proper medical attention.’

The thought filled Lebret with hazy dread. ‘What must I do?’ he asked, as if through a mouthful of pebbles. ‘What treatments do you have?’

‘I cannot help you,’ Dakkar gasped, and closed his eyes.

‘Do you have penicillin?’

Dakkar did not reply.

As time passed, Lebret felt increasingly sluggish, hot and miserable. A trembling started up in his hands and head. ‘I feel terrible,’ he informed Dakkar. The latter did not reply. It was hard to see if he were even breathing.

More time passed – Lebret could not say how much. He felt increasingly unwell, and soon reached a state where all his sensations and thoughts were subordinated to the pressing misery of his physical discomfort. His face was sweltering, his eyes wincing and weeping. Shivers passed all over his body.

Hours passed. Perhaps it was days. The fever seemed to reach a point of maximum intensity, when agony in his jaw throbbed continually, and he sweated and wept and floated. The physical discomfort was compounded of a kind of existential bitterness – to have

survived

such ill fortunes as being shot in the face, and drowned in an infinite ocean, only to die of a stupid infection – it was insulting.

Then, very slowly, the fever drew itself back in, until Lebret’s symptoms resembled a bout of regular flu, and he was able to move himself around with painful slowness. He drank a great draught of water, and then – uncaring – relieved himself into the same place.

The white blank screen was pulsing with pale light.

‘Dakkar! Dakkar – what does it mean?’

Dakkar looked very near death. He roused himself, peered for a long time at the screen, and said, ‘The submarine is here.’

‘The

Plongeur

? Here?’ gasped Lebret, shivering. ‘Bring them inside! Open a corridor to the vessel’s air-lock.’ In his sickness he had lost the fear that Billiard-Fanon might take one look at him and shoot him dead. He craved company. Indeed, he craved being looked after; nursed, treated with the penicillin he knew existed within the vessel’s First Aid Box.

But Dakkar shook his head. ‘Not,’ he said. ‘Possible.’

‘How are they to get in here, then?’

It took Dakkar an age and an age to answer. ‘Swim.’

‘But there are no more suits! Wait – can I speak to them?

Without speaking, Dakkar crooked a finger at the screen. Trembling, feeling child-like again in the grip of his flu-symptoms, Lebret retrieved the technology. It unsnibbed easily from the wall. Waves of fever swept through Lebret’s consciousness. He felt nauseous. His throat was tight. ‘What do I do?’

Dakkar paddled one wizened finger against the shining board, and then fell back.

‘What now?’ Lebret wheezed. Despite the analgesic mallows, pulses of agony were radiating out from the side of his head. His brain was a monsoony, defocused, worn-out place. But Dakkar

had fallen asleep, or lost consciousness, his gigantic head rolling backwards and the momentum of it causing his torso to swing round and rotate in mid-air.

‘Hello?’ said the shining board. It was Capot’s voice.

Tears were dribbling from Lebret’s eyes. It astonished him how relieved he was to hear the young sailor’s voice. ‘It’s me! It’s me!’

‘Who? Who is that?’ A second voiced chimed in. ‘Where is that voice coming from?’

‘Is that

you,

Pannier?’ wheezed Lebret. ‘God, it’s good to hear you again, you old drunkard!’

‘Who

is

that?’

‘Don’t you recognise my voice? I suppose I’m ill – my jaw is swollen, and I think my throat is constricted a little. I probably do sound different. It’s me – it’s Jean Lebret!’

There was a pause. Then Capot whimpered, ‘Lebret.’

Pannier said, ‘Can you hear this, Castor? It’s not coming through on the radio – can you hear it?’

‘I can hear it,’ came Castor’s voice. ‘How is it broadcasting in here? Is it piggybacking the speakers – it’s audible throughout the whole vessel!’

‘I don’t know how it works,’ Lebret croaked. ‘I am in a chamber, with – with somebody you will want to meet. There are various items of advanced technology here, one of which I am presently using, although I don’t know how, to speak to …’

‘Lebret!’ shrieked Capot, suddenly. ‘Lebret – stop tormenting me! I never harmed you in life; why should you pursue me after your death … ?’

‘I’m not dead,’ Lebret began, but another voice – Billiard-Fanon’s – came across the device. ‘Lebret!’

‘Listen, Billiard-Fanon – don’t leap to any conclusions …’

‘I shall leap nowhere,’ said Billiard-Fanon. ‘I have received a vision from God Almighty! I

understand

the true nature of where we are.’

‘You have come to a halt,’ Lebret gasped. ‘You know it! Go to the observation chamber, and take a look – you’re resting upon a

gigantic scallop shell. I know this to be true, because that’s where I landed, a little while ago.’

‘How did you … ?’ Castor started to ask. But Pannier spoke across him. ‘Are you dead?’

‘No, not dead, though I am hurt,’ said Lebret. ‘You must come inside – you’ll be amazed. I can explain everything.’

The low-key wailing sound was Capot moaning. ‘

How

did you survive?’ Pannier pressed.

‘You mean, after Billiard-Fanon shot me in the mouth?’ Lebret replied.