Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (36 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

‘Instruct me in the ways of nuclear fission,’ said the Jewel.

The profound oddness of the moment kept sliding out of Jhutti’s mind. As if it were a

reasonable

thing! – to have sunk to the bottom of the deepest ocean in the world in company of a madman only to be quizzed on his knowledge of nuclear physics by a giant geometrical shape. He said, ‘You do not understand the principles of an atomic pile?’

‘I do,’ said the Jewel. ‘Don’t you?’

‘Of course.’

Looking more closely, Jhutti could see that the bullet Billiard Fanon had fired was lodged

inside

the body of the structure. A line composed of dots – miniature bubbles – showed the trajectory it had taken before coming to a halt. Jhutti realised that though it

looked

crystalline – the word ‘tetragrammaton’ came into Jhutti’s head, from whence he knew not – it was actually composed of some strange jelly-like substance. As to how it had suddenly manifested … Jhutti couldn’t even guess. He almost reached out to touch it; but held himself back.

‘Why ask me, if you already know the answer,’ Jhutti said.

‘It should, I think, be obvious why I am asking you,’ replied the Jewel, with a note of asperity in his voice.

‘God, God, God, God,’ cried Billiard-Fanon again. ‘Do not talk to

him

! He is a heathen. I am the chosen one!’

‘Be quiet,’ the Jewel instructed him.

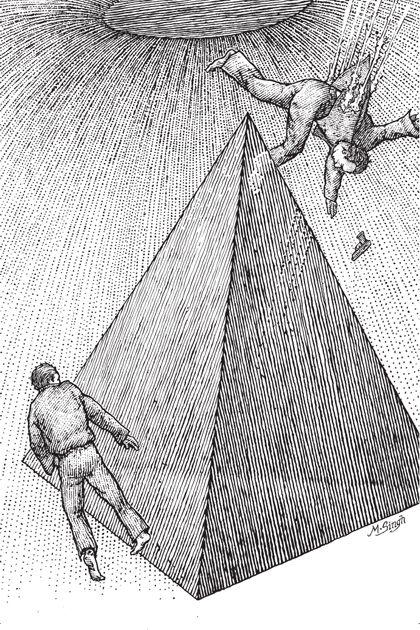

‘Restore gravity to this place, O God,’ Billiard-Fanon pleaded, ‘that we may kneel before you! That we may abase ourselves!’

‘I am not here for

you

,’ the shape said again, crossly. ‘I am here for Amanpreet Jhutti, expert in the engineering of nuclear power.’

‘But why?’ Jhutti asked.

Billiard-Fanon howled, like a dog. ‘My God-God-God-God,’ he yelled. ‘Why have you forsaken me? Or are you a devil? But that cannot be the case!’ Jhutti could see him aiming his pistol once again, pointing it at the shape. ‘I am the Holy One, and the truth is clear to me – the truth of the sacrifice of Jesus Christ. God must die, and I must kill him! God must die to be reborn again …

as me

!’

Billiard-Fanon discharged the pistol five times in quick succession. The noise was appalling, deafening, and Jhutti put his hands over his ears. Each of the bullets entered the body of the tetragrammaton, slowed and stopped.

The shape seemed to grow, to swell, and then – with a clonic jerk – it contracted. The six bullets were squeezed from its body like pips from an orange. All six converged back on their point of origin. Billiard-Fanon did not even have time to cry out. The impacts caused all four of his limbs to fly outwards, and sent his body karooming straight back to collide with the wall behind him.

‘No!’ shouted Jhutti.

‘Be quick!’ the tetragrammaton demanded. ‘At this –

distance

– it is very hard for me – to maintain co –

herence

. Answer my question!’

‘Are you God?’ Jhutti gasped.

‘No,’ the answer rang out.

‘Did you bring this submarine here so as,’ Jhutti asked, stopping halfway through the question because it seemed too absurd. Shortly he finished: `… so as to speak to

me

?’

‘Yes,’ said the tetragrammaton. ‘To ask you two questions! And you must answer them!’

‘Very well,’ said Jhutti, trembling a little. He looked past the shape at Billiard-Fanon’s lifeless corpse.

‘Do

you

understand the principle of nuclear fission?’

‘After seven years of post-doctoral research, I should hope I do.’

‘Do

you

understand the principle of nuclear fusion?’

‘Fission? Yes, yes I do.’

‘No! Do

you

understand the principle of nuclear

fusion

?’

‘Ah, pardon me, I misheard. Fusion? I understand the principles,

I suppose. It is what happens in the heart of the sun. But as for making it happen on earth, inside a manmade reactor? We are a long way away from that, I’m afraid.’

And with that answer, the tetragrammaton vanished, de-appearing with a gust of air and a slight squelching noise. Jhutti was alone.

‘Good gracious,’ he said, pushing himself off to float over towards Billiard-Fanon’s body and check for a pulse. ‘Am I truly the last one alive? What to do now?’

To be weightless in air. To be weightless in water.

Lebret couldn’t see anything. He wasn’t breathing air into his lungs, and that fact disturbed him – felt wrong, awkward. He wasn’t hot. He felt cold, he supposed; which is to say, he

must

feel cold, since he didn’t feel hot. But actually, he didn’t feel anything. He could not move his arms or legs.

He was not alone. He could not tell who was with him. He was dead. Was this how it was, being dead? He could not move the muscles that operated his eyelids; but he did not need to – his eyes were open. But he could not move the tiny ring of muscle inside his eye to bring the half-lit blurry mess of grey-green into focus. Was he dead? He considered this. It seemed to him an important question. Indeed, now that he came to think of it he wasn’t sure it was possible to ask a

more

important one. He framed it in his mind. It was always there. It was the ocean bed underlying all our watery consciousness. He asked, ‘Am I dead?’

‘Just so,’ said his companion.

Lebret did not move his lips or tongue; and he expelled no air with his diaphragm – indeed, he had no air to expel. Nonetheless he asked, ‘Who are you?’

‘I am the Jewel.’

This did not help. Lebret tried a different question, ‘

Where

are you?’

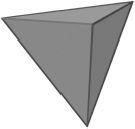

‘Here.’ As soon as this word appeared in Lebret’s sluggish

brain, he could see – directly in front of his eyes. A crystalline tetrahedron. It rotated slowly, glinting greenly in the dimness.

‘You are an emerald!’ Lebret cried. But then he looked again, and it seemed to him that the shade was more blue than green. ‘Or a sapphire?’ And as he said this, it seemed to him that the gemstone darkened, became more richly green until it spilled into a deep, rich blue.

The faceted shape swung round, and Lebret caught a glimpse of himself in one of its triangular facets. His face was swollen and deformed, eyes glassy. But his eyes were evidently still operational, or how else could he see himself? Twice killed, and twice resurrected, he thought. Shot in the head; poisoned with sepsis; still alive. The strands of Dakkar’s beard were fixed to his chin, and were swaying in the slight current.

‘I thought them dead,’ Lebret said. ‘Those – whatever they are. Eels. Worms.’

‘Water revived them. They were never truly alive, to die.’

‘And you are connected to me – through them?’

‘Yes,’ said the Jewel, simply.

‘So for that purpose – you must forgive me for reverting to this question, but it concerns me.

For

that purpose, does it not matter that I am – dead?’

‘I have had some time to work with folk, such as you are. Yours is a strange substrate for consciousness – or so it seems to me. A soft and spongy brain, yet it retains all its neuronal connections, even after death. It is a simple matter to make it work.’

‘Simple for

you

,’ thought Lebret, bitterly.

‘Yes,’ agreed the Jewel.

‘The substrate of

your

consciousness, then, is crystalline?’

‘As you can see.’

‘But, clearly, you are not physically present. Dakkar said that you were a trillion kilometres away.’

‘Indeed. But I am bringing the shell

to

me. And you with it.’

‘A trillion miles!’ said Lebret. ‘That will take … hundreds of years!’

‘It will indeed take some time, although not so long as that. But there is plenty of time.’

‘Dakkar told me not to trust you,’ said Lebret. ‘He said you intended to conquer my world.’

‘I do,’ agreed the Jewel, readily. ‘

When

I have you, and your companion, here with me,

then

I shall move ahead with that project.’

‘I shall not assist you!’ Lebret declared fiercely. ‘I shall resist.’

‘I have learnt a good deal from the unexpected resistance of Dakkar,’ the Jewel said. ‘I shall apply what I have learned. I do not believe you will be able to resist.’

‘But why?’ cried Lebret. ‘What good will it do you?’

‘I have studied your cosmos, as best I can,’ said the Jewel. ‘It is a passing strange place. But each of the four universes is different from the other three, and each must seem strange to the inhabitants of the others, I suppose.’

‘Four

universes?’

‘The tetraverse,’ confirmed the Jewel. ‘Did you think your vacuuverse the only cosmos? How could you believe such a bizarrely improbable thing?’

‘It is the nature of consciousness to think itself unique, I suppose,’ Lebret mused, mentally. Not a one of his muscles moved. He was neither hot nor cold. ‘And therefore to gift its surroundings with uniqueness too. I thought my world the only one. Or I

did

, until we stumbled into this … strange place. A waterverse! I could not believe an infinite space filled with water could exist. Is this cosmos infinite?’

‘Geometrically, yes indeed; just as yours is. But it is of finite mass, as yours is. Indeed, all four iterations of the tetraverse manifest balance in terms of total mass.’

‘What do you mean?’

The Jewel began to rotate more rapidly, spinning smoothly. Lebret saw his own drowned face flashing in each of the triangular facets in turn.

‘I have studied the other three universes, as far as I have been able,’ said the Jewel. ‘Of course I have! Of

course

I have.

Your

universe is – I speak very approximately – a sphere with a radius of 10

30

light years. Naturally, yours is a

vacuum

cosmos. Matter is spread in varying degrees of irregularity throughout it, but overall the constituent atoms are spread

extraordinarily

tenuously. When you look at the total picture – on average, the density of

your

cosmos is one hydrogen atom in every four cubic metres of volume. That is a medium whose density is about 10^30 times less than water. And the

result

of this strange harmonious coincidence of numbers – which, of course, is no coincidence at all, but rather an expression of underlying geometric truths about the constraints on any existing universe – the result of this congruence is that the waterverse must be

one times ten-to-the-one-thirtieth

the size of the vacuuverse.’

‘In other words,’ said Lebret, working the sum in his head, ‘it must be … only

one

light-year across—’

‘One light year

radius

. Two light years across. Approximately twenty trillion kilometres. If you wish a comparison, to help visualise the size – twenty trillion kilometres is the size of your own solar system.’

Lebret thought about this. ‘I would have guessed that the orbit of Pluto would be considerably less than …’

‘Pluto? Nonsense! What is Pluto? Pluto is neither here nor there.’ The Jewel was spinning more rapidly now, as if winding itself up with its own discourse. ‘No, from the sun in the centre out to the edge of your sun’s

heliopause

. The Oort cloud. You know the Oort cloud?’