Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea (32 page)

Read Twenty Trillion Leagues Under the Sea Online

Authors: Adam Roberts

The tendrils jabbed and bit at the diving suit material, like malignant blind snakes, but they could not penetrate its thickness.

It occurred to Lebret to wrap his left hand in a fold of the stuff, and use it to pull out clumps of beard. The tendrils snapped easily enough, although it was a neater business scraping the knife blade over the skin.

The moustache was removed, and Lebret started up the right cheek. The skin that he revealed was a strange thing. Evidently stretched and distorted by being enlarged from Dakkar’s original proportions, the pores were widened further by this monstrous self-aware beard. Finally he scraped Dakkar’s neck clean, and floated back to admire his handiwork.

The air was filled with floating tendrils, most curling and twisting with repulsive motion, and winking their little mouths. But Dakkar’s weirdly huge face was clean-shaven, now. In only a few places had Lebret nicked the skin.

The subject was still breathing, but his eyes were tight shut and he was unconscious. Lebret left him floating, and occupied a quarter of an hour moving around the chamber with the diving-suit, using it as a form of net to collect together as many of the still wriggling strands as he could. This was tricky, but he managed to bundle the majority into a parcel, and this he sealed by tying together the arms and legs into knots.

He was thirsty. The painkiller was beginning to wear off; he could feel the pain in his jaw looming back into consciousness, like jagged rocks appearing through fog. He stuck his head into the bulb of water, drank deeply and washed his face.

Then he waited. His hand was red and itchy where the tendrils had bit him, but he could still move it.

His thoughts went back to the strange dream he had experienced, immediately before Dakkar had re-entered the space. Had it been a dream, or a telepathic vision? Had the Jewel – whatever that evidently potent, alien entity

was

– actually been communicating with him? If so, perhaps it was not to be trusted.

Dakkar stirred, moaning a little. ‘Your haircut is complete, M’sieur,’ Lebret told him. ‘I feel I should charge you a franc. How do you feel?’

‘It is agony,’ Dakkar groaned.

‘Still? Even with the … the tendrils removed?’

‘They were wired into my nervous system, beneath the skin; enough of them remain to cause me pain. Still – I thank you, Monsieur. You have done me a great service! My mind is clearer, despite the pain. And as for that … well, it is nothing more than I deserve.’

‘Deserve? Surely not, M’sieur!’ declared Lebret.

‘I came down here with a crew of my own, Monsieur Lebret. I led them down here. The Jewel did this to me, but he did worse things to

them

.’

‘What did he do?’

‘He is fascinated by the prospect of our world,’ said Dakkar, in a rasping voice. ‘And naturally his mind runs to domination. It is his nature.’

‘He wishes to invade our world? To conquer it?’

‘I find myself almost incapable of condemning him for it! He can only think in those terms, he has no choice. But our world, our

reality

, presents him with a problem. Oxygen.’

‘Oxygen?’

‘It is a rare element down here.’

‘But how can that be? Every molecule of water is one third oxygen!’

‘True, of course,’ Dakkar conceded, wheezing. ‘But that oxygen is locked so tightly into its chemical bonds it takes prodigious energy to release it. No, the problem is

free

oxygen. At the beginning, the Jewel even refused to believe that there was such a thing – even though he had us, and could see that we breathed in the gas.’

‘Why?’

‘Why did he doubt it? Because oxygen is immensely reactive – stupendously so. What, after all, is fire but the aggressive oxidisation of whatever is burning? Think of it from his point of view. Imagine a creature came to you from a realm of fire, and reported that in amongst the brimstone hills and burning plains were lakes of pure petroleum. Wouldn’t you doubt him – for surely the petroleum would all long since have been long ago burnt up by the surrounding fires? That is how the presence of so much free

oxygen in our atmosphere appears to

him

. It ought long since to have been burnt up!’

‘The oxygen is replenished by the action of photosynthesising plants,’ Lebret said.

‘Exactly. And in time he experimented with oxygen-producing algae. But even his best efforts were tepid compared to the naturally occurring flora of our terrestrial homes. His created algae serve as the ground for the various ecosystems he has established around the various stars near here, but they breed slowly and die out easily, and the higher organisms he designed live on the threshold of oxygen deprivation.’

‘They seemed to go crazy for air when the

Plongeur

passed through them,’ Lebret recalled.

‘They would!’ said Dakkar. ‘Have you seen fish in a dying pond, gulping desperately at the surface? Poor things, they are trapped at their various stars – stray too far, away from the algae, and there is no free oxygen dissolved in this water at all. A fish would drown in this ocean as quickly as a man. But even close by the star there is precious little.’

‘He

made these beasts? The Jewel?’

Dakkar nodded. His skin had acquired a grey, exhausted tone to it; and his eyes seemed to be having trouble focusing. ‘He took my crew – adapted them, cloned them, perverted their forms.’

‘But why?’

‘Isn’t it obvious? He hoped to breed a new species capable of swimming through the oxygen rich oceans of the earth. He has many creatures, but none that could bear to swim such waters.’

‘An invasion force!’ murmured Lebret. ‘Surely your crew would never agree to spearhead such an attack?’

‘Oh, their humanity is long since gone, dissolved in the crucible of his

work

. I believe he intended them to retain

some

wit, some level of mental capacity. But they are born, live and die in such an oxygen-starved environment their brains are poisoned. They are blind knots of instinct. I brought them here, and such was their fate! You can see why I consider my pain deserved?’

‘You cannot have known, Prince Dakkar!’ urged Lebret. The

pain in his own jaw was growing now, and his leg was starting to tingle and sting. ‘You cannot blame yourself!’

‘You cannot conceive what it has been like,’ said Dakkar, tears leaking from between his closed eyelids. ‘The Jewel attached that – beard to my face, that entity to my brain. Since then I have lived a tormented existence.’

‘Come!’ said Lebret, uncertainly. ‘I say, do you happen to have any more of those very effective painkillers on your person?’

Dakkar only groaned.

For a long time they were both silent. Lebret was beginning to feel hungry; and the ache in his jaw was increasing unpleasantly.

‘I’m sorry about your teeth,’ said Dakkar.

Lebret started. ‘I thought you were asleep.’

‘I am dying,’ said Dakkar.

‘Because I shaved your beard? But why did you permit me to do it, if it must kill you?’

‘I am very old,’ said Dakkar. ‘What year is it, back in France?’

‘1958.’

‘Well! In that case I am a more than a hundred and fifty years old. The beard was keeping me alive. The Jewel was prolonging my life. He valued what I had in my head – my memories of earth, my ingenuity, and the thought that he could use me as a tool to help him invade the earth.’

‘There must be something I can do!’

‘You are the first fellow human I have seen in decades,’ Dakkar said, mournfully. ‘I could not have done this thing unaided – and so I thank you.’ He appeared to fall asleep.

Days passed, with Dakkar moving in and out of consciousness. The pain in Lebret’s jaw grew fierce again, but it took coaxing to persuade Dakkar to fetch more painkillers. ‘There is a garden attached to this facility,’ the old man explained. ‘For unlike the Jewels, I need organic sustenance to subsist, and that is where I grow my meals.’

‘Jewels?’ Lebret asked, sharply. ‘Plural?’

‘What?’ replied Dakkar, vaguely.

‘You said Jewels, as if there are many. Earlier you talked of one Jewel. Which is it?’

‘I don’t,’ said Dakkar, ‘I don’t follow—’

‘Never mind. You grow analgesics in this garden, as well as food?’

‘At my age, aches and pains are a serious matter.’

‘Can you fetch me some?’ Lebret begged. ‘The pain in my jaw is becoming hard to bear. And I feel hot – I feel feverish all over.’ It was true; he was beginning to shudder with the onset of what felt like flu.

‘I am too ill to go,’ Dakkar insisted. ‘And besides, without my beard how am I to breathe underwater?’

‘The water in that space

is

oxygenated, then?’

‘There is a small generator, drawing on infraspace for its power. It divides water to create the oxygen, both for the water in the chambers beyond the bubble, and in this space.’

‘Well if you cannot swim down to this garden, I suppose I must,’

said Lebret briskly, for his pain was making him impatient. ‘Can you help me refill my air-tanks?’

‘You mean your diving equipment?’ Dakkar looked listlessly at the three tubes of tarnished metal. ‘The air must be compressed,’ he said. ‘I would need to create a new machine, and I am sorry to say I do not have the energy.’ He closed his huge eyes, wearily.

‘How far is it? Could I swim there and back on a lungful of held breath?’

‘Perhaps, if you were to hyperventilate a little – like the pearl fishers of Sumatra! Come, help me to the water and I will show you.’

Lebret guided Dakkar’s floating body to the bulb of water. Wearily the old man pulled himself through to the other side; and Lebret pushed his own head through. Blinking, he saw Dakkar gesture listlessly towards the far end of the flooded space. When they both pulled themselves back into the air, the old man explained. ‘Through that gateway, and you’ll see. I grow food, medicines, various things. The difficulty for you will be that many of these items will be indistinguishable to you – they all look like white mallows, growing in racks. I know what they are, but you will have to harvest as wide a range as possible, and discover their particular virtues by experiment afterwards.’

‘Very well.’

‘It means,’ gasped Dakkar, ‘that you will certainly bring some food back as well. And I am hungry!’

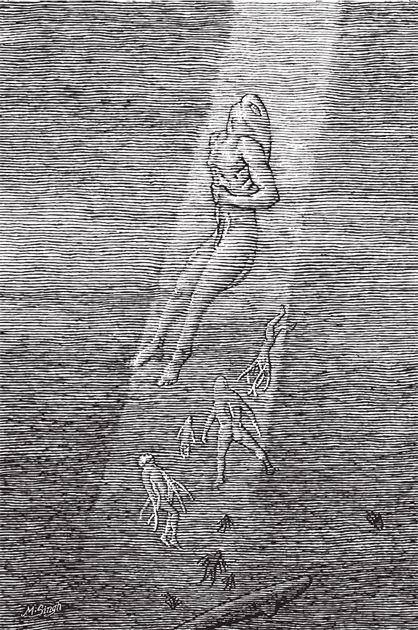

‘I’ll do my best,’ Lebret spent long minutes breathing in and out as deeply as he could, until he felt thoroughly dizzy. Then he slipped into the water like an acrobat through a circus hoop.

Swimming was not easy with his wounded left leg, but by dint of wriggling and paddling furiously with his hands, he made it to the end of the first watery chamber. Through the gate and he entered a brighter space – lamps shining on the grids and racks of genetically modified mallow-like growths. His breath was still good, so he took a moment to look around – it was another entirely enclosed chamber, filled with water, and with three sealed

doors below, or along from, the lights. He quickly plucked as many as he could, and wriggled back to the chamber of air.

‘There,’ he said, releasing indistinguishable blobs of white from his arms to float through the air. Dakkar indicated one that had analgesic properties; and then the two of them ate several of the protein and vitamin morsels. They were flavourless.

Afterwards, Lebret asked more questions. Some of these Dakkar answered cogently enough; with others he appeared to drift off. He was paler now, and wrinkles were appearing around the edges of his face – as if his oversized head were actually beginning to shrink. The hair on the top of his head contained streaks of white that had not been there before.

‘I am trying to understand,’ Lebret said. ‘This gemstone entity – he seeks to conquer our world?’

‘Yes.’

‘And to that end he created a number of sub oceanic suns! An entity with such powers could surely simply seize the earth – make a sun over New York to burn the city to ashes, say, and cow the rest of the globe with threats of similar terrors!’

‘You do not grasp the nature of things here,’ said Dakkar, croakily. ‘This is his realm. It is his nature to have access here to the skein that separates infraspace from superspace – from the space we occupy and are in the habit of calling the universe. I do not doubt that one reason he hopes to break through into

our

world is to see whether he has similar control there. But as it stands, he knows very little about the earth.’