Two Miserable Presidents (8 page)

Read Two Miserable Presidents Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

F

rank Thompson was living in Michigan when the Civil War began. “What can I do?” Thompson wondered. “What part am I to act in this great drama?” Friends marched off to join the Union army. Thompson longed to join them. There was only one difficulty: Frank Thompson was actually a nineteen-year-old woman named Sarah Emma Edmonds.

rank Thompson was living in Michigan when the Civil War began. “What can I do?” Thompson wondered. “What part am I to act in this great drama?” Friends marched off to join the Union army. Thompson longed to join them. There was only one difficulty: Frank Thompson was actually a nineteen-year-old woman named Sarah Emma Edmonds.

Two years earlier, Sarah had been living with her family in Canada. One day her father announced that he had picked out a husband

for herâa much older man she didn't really like. Sarah dressed up as a man, crossed the border into the United States, and told Americans she was Frank Thompson. Soon she found a job as a traveling book salesman.

for herâa much older man she didn't really like. Sarah dressed up as a man, crossed the border into the United States, and told Americans she was Frank Thompson. Soon she found a job as a traveling book salesman.

In May 1861 “Frank Thompson” enlisted in the Union army. Doctors were supposed to carefully examine all volunteers, but they usually didn't bother. One Union soldier described a typical army exam.

Doctor:

You have pretty good health, don't you?

You have pretty good health, don't you?

Volunteer: Yes.

Doctor:

You look as though you did.

You look as though you did.

That was the whole exam. Which explains how Sarah Edmonds became part of the Second Michigan Regiment.

Others members of the Second Michigan looked at Sarah's smooth, hairless face and figured they were seeing a young boy who had lied about his age to get into the armyâthat was pretty common. Soldiers didn't actually change their clothes very often, which made it easy for Sarah to remain in disguise.

About five hundred women served as soldiers in the Civil War. Some did it for the excitement, others to escape a bad home life. Some joined for the moneyâthe soldier's salary of thirteen dollars a month was much more than young women could earn in jobs that were open to them.

Loreta Janeta Velazquez was one of the women who joined the army in search of adventure. “I was perfectly wild on the subject of war,” she remembered. At age nineteen she decided “to enter the Confederate service as a soldier.”

Velazquez was living with her husband in Tennessee when the

war started. He quickly set off for Richmond to join the army. “My husband's farewell kisses were scarcely dry upon my lips,” she said, “when I made haste to attire myself in one of his suits, and to otherwise disguise myself as a man.”

war started. He quickly set off for Richmond to join the army. “My husband's farewell kisses were scarcely dry upon my lips,” she said, “when I made haste to attire myself in one of his suits, and to otherwise disguise myself as a man.”

She entered the Confederate army as Harry T. Buford. “This is the kind of fellow we want,” said an officer, shaking her hand. “And with a few more of the same sort, we will whip the Yankees inside of ninety days.”

Everything went fine for “Lieutenant Buford” until one scary moment at a crowded dinner table. She took a big gulp of buttermilk, soaking her fake mustache. When she tried to wipe the mustache, it started to come off. “To say that I was frightened, scarcely gives an idea of the cold chills that ran down my back,” she later said. She described eating the rest of the meal with “my hand up to my mouth all the time ⦠doing my best to hold the mustache on.”

Velazquez made it through the meal. And a little while later she marched off to war.

Loreta Janeta Velazquez

M

eanwhile, Abraham Lincoln was having a rough winter. McClellan was still camped in Washington, still claiming he needed more time to get ready.

eanwhile, Abraham Lincoln was having a rough winter. McClellan was still camped in Washington, still claiming he needed more time to get ready.

In February 1862, Lincoln's eleven-year-old son Willie became ill with typhoid fever. Abraham and Mary watched their son get weaker and weaker and finally die.

“It is hard, hard, hard to have him die!” Lincoln cried at Willie's bedside.

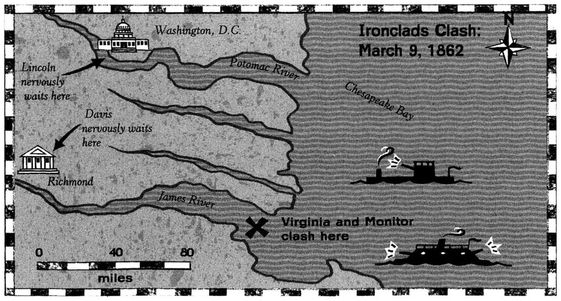

Then, in early March, an alarming report sent Lincoln and his advisors into a panic. A strange new Confederate ship was cruising around Virginia. The ship, Lincoln learned, was once a wooden warship called the

Merrimac

. But the Confederate navy had attached thick sheets of iron to its sides and a long iron beak to its front. They renamed it the

Virginia

. The

Virginia

was so heavy that it had a top speed of just five miles per hourâand it took a half an hour to turn around. Still, it had a huge advantage over the Union's wooden warships.

Merrimac

. But the Confederate navy had attached thick sheets of iron to its sides and a long iron beak to its front. They renamed it the

Virginia

. The

Virginia

was so heavy that it had a top speed of just five miles per hourâand it took a half an hour to turn around. Still, it had a huge advantage over the Union's wooden warships.

On the morning of March 8, 1862, several of those Union ships were guarding the mouth of the James River in Virginia, blocking Confederate ships from getting out to sea. It was a warm morning and Union sailors were splashing and swimming in the river. They looked up and saw what appeared to be a giant barn, with just its slanted roof sticking out above the water. This was the

Virginia

, steaming toward the Union ships in a slow-motion charge.

Virginia

, steaming toward the Union ships in a slow-motion charge.

Union sailors scrambled onto their ships and opened fire on the

Virginia

. The men were amazed to see their eighty-pound cannonballs bouncing off their target like “peas from a pop-gun,” one sailor said. The Virginia's chief engineer, H. Ashton Ramsey, described the scene. “We were met by a ⦠storm of shells ⦠. They struck our

sloping sides, were deflected upward to burst harmlessly in the air, or rolled down and fell hissing into the water.”

Virginia

. The men were amazed to see their eighty-pound cannonballs bouncing off their target like “peas from a pop-gun,” one sailor said. The Virginia's chief engineer, H. Ashton Ramsey, described the scene. “We were met by a ⦠storm of shells ⦠. They struck our

sloping sides, were deflected upward to burst harmlessly in the air, or rolled down and fell hissing into the water.”

The

Virginia

cruised straight at the Union ship

Cumberland

.

Virginia

cruised straight at the Union ship

Cumberland

.

“Do you surrender?” shouted the captain of the

Virginia

.

Virginia

.

“Never!” the captain of the

Cumberland

replied.

Cumberland

replied.

Moments later the

Virginia's

iron beak slammed into the

Cumberland

, cracking a huge hole in the side of the wooden ship. Union sailors jumped off the

Cumberland

as it sank to the bottom of the river. The

Virginia's

iron beak snapped off and sank too.

Virginia's

iron beak slammed into the

Cumberland

, cracking a huge hole in the side of the wooden ship. Union sailors jumped off the

Cumberland

as it sank to the bottom of the river. The

Virginia's

iron beak snapped off and sank too.

Even without its beak, the

Virginia

destroyed another Union warship. And before nightfall, three more Union ships got stuck on sandbars while trying to escape the

Virginia's

guns.

Virginia

destroyed another Union warship. And before nightfall, three more Union ships got stuck on sandbars while trying to escape the

Virginia's

guns.

The

Virginia

would be back tomorrow to finish the job.

Virginia

would be back tomorrow to finish the job.

W

hen Lincoln heard about all this, he ran to the White House window to see if the

Virginia

was cruising up the Potomac River to destroy Washington.

hen Lincoln heard about all this, he ran to the White House window to see if the

Virginia

was cruising up the Potomac River to destroy Washington.

It wasn't. In fact, the secretary of the navy, Gideon Welles, gave Lincoln some good news: the Union had a new ironclad ship of its own, the

Monitor

. And the

Monitor

was cruising to the James River right at that moment.

Monitor

. And the

Monitor

was cruising to the James River right at that moment.

The next morning, March 9, the

Virginia

steamed out into the James, ready to finish off the Union warships. Confederate sailors decided to start with the

Minnesota

. But what was that new, weirdlooking boat in the river?

Virginia

steamed out into the James, ready to finish off the Union warships. Confederate sailors decided to start with the

Minnesota

. But what was that new, weirdlooking boat in the river?

“We thought at first it was a raft on which one of the

Minnesota's

boilers was being taken to shore for repairs,” said a

Virginia

sailor. Then the raft suddenly starting shooting at them! This was no repair raftâit was the Union ironclad

Monitor

.

Minnesota's

boilers was being taken to shore for repairs,” said a

Virginia

sailor. Then the raft suddenly starting shooting at them! This was no repair raftâit was the Union ironclad

Monitor

.

For four hours the

Virginia and Monitor

blasted their big guns at each other, sometimes from just a few yards apart. Inside the ships, men's eardrums burst and bled from the deafening crash of cannonballs slamming into solid iron. The larger, more powerful Virginia tried to ram into the

Monitor

âbut it couldn't catch the smaller, quicker Union ship. Though both crews were battered and exhausted, neither ironclad was able to seriously damage the other.

Virginia and Monitor

blasted their big guns at each other, sometimes from just a few yards apart. Inside the ships, men's eardrums burst and bled from the deafening crash of cannonballs slamming into solid iron. The larger, more powerful Virginia tried to ram into the

Monitor

âbut it couldn't catch the smaller, quicker Union ship. Though both crews were battered and exhausted, neither ironclad was able to seriously damage the other.

Who won the world's first battle between iron ships? “We of the

Monitor

thought, and still think, that we had gained a great victory,” said a Union officer. But the

Virginia

sailors were equally convinced that they had won the day.

Monitor

thought, and still think, that we had gained a great victory,” said a Union officer. But the

Virginia

sailors were equally convinced that they had won the day.

Either way, one thing was clearânavies all around the world needed to start building iron ships.

N

ow the action moves to the west, where there was some good news for Abraham Lincoln. It came from a surprising source: a Union general named Ulysses S. Grant.

ow the action moves to the west, where there was some good news for Abraham Lincoln. It came from a surprising source: a Union general named Ulysses S. Grant.

Growing up in a small Ohio town, Ulysses was a shy and quiet kid. Bigger kids used to call him “Useless” Grant. And most kids were bigger. At age seventeen, Ulysses stood just five foot one and weighed 117 pounds. He graduated from West Point and fought in the Mexican War, but he was later forced to resign from the army when he began drinking heavily. Then he failed at one job after another. When the Civil War began, Grant was working as a clerk in his father's leather store in Illinois.

He rejoined the army, but no one expected much. Even Grant had doubts about himself. While leading soldiers into one early battle in Missouri, he was so scared, he thought his heart was going to burst through his throat: “I would have given anything then to have been back in Illinois,” he said.

Grant marched his men over a hill and looked down at the field where he expected to see a Confederate army led by Colonel Thomas Harris. But Harris and his army had already marched away. Grant was relievedâand he learned a lesson that changed his life:

“It occurred to me at once that Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him. This was a view of the question I had never taken before; but it was one I never forgot afterwards.

After this experience Grant became a completely different kind of military leader. He quit worrying about what his enemy was going to do to him. From then on, he would worry only about what he was going to do to his enemy.

Other books

Dreaming of the Billionaire by Bright, Alice

Blood Feud by Rosemary Sutcliff

Stone (The Forbidden Love Series Book 1) by Angel Rose

The Night Is Watching by Heather Graham

Friends Forever! by Grace Dent

A Quiet Flame by Philip Kerr

Dancing in Red (a Wear Black novella) by Hiestand, Heather, Flynn, Eilis

Breath of Heaven by Holby, Cindy

After the Fall: Jason's Tale by David E. Nees

Collection 1986 - The Trail To Crazy Man (v5.0) by Louis L'Amour