Two Miserable Presidents (12 page)

Read Two Miserable Presidents Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

G

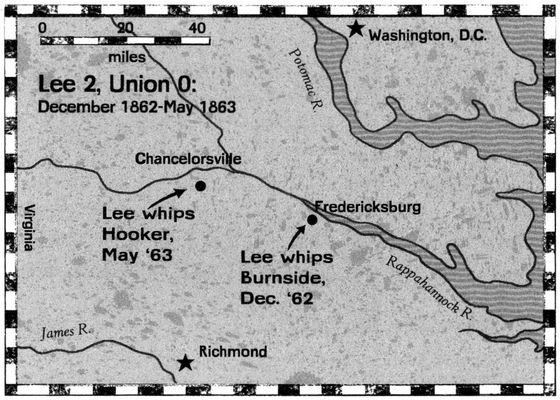

eneral Lee watched his army win an easy victory at the battle of Fredericksburg. It was so easy, he had to remind himself that combat was not supposed to be fun. He turned to General James Longstreet and said, “It is well that war is so terribleâor we should grow too fond of it.”

eneral Lee watched his army win an easy victory at the battle of Fredericksburg. It was so easy, he had to remind himself that combat was not supposed to be fun. He turned to General James Longstreet and said, “It is well that war is so terribleâor we should grow too fond of it.”

There was no danger of Burnside becoming too fond of war. That night he paced back and forth in his tent, pointing to the blood-soaked battlefield and crying over and over, “Oh, those men! Those men over there! I am thinking of them all the time!”

There were a lot of them to think about. More than 12,000 Union soldiers were killed or wounded at Fredericksburg. Lee lost about 4,000 men.

Surgeons on both sides were busy for days. Men who were badly wounded in the vital organs of the chest or stomach had little chance of surviving. Doctors simply did not know how to deal with these kinds of wounds. So surgeons spent much of their time working on smashed arms and legs, often by cutting them off. The best army surgeons could amputate a limb in about ten minutes.

Soldiers got used to seeing amputated arms and legs piling up outside battlefield hospitals. But a Union soldier named William Hamilton saw something especially disgusting at Fredericksburg. “There was a hospital within thirty yards of us,” Hamilton wrote to his mother. “About the building you could see the hogs belonging to the farm eating arms and other portions of the body.”

Sadly, soldiers who had their arms or legs amputated did not always get healthy. Doctors in the 1860s understood a little about germs, but they didn't know how to kill the germs on their hands or instruments. “We operated in old blood-stained and often pusstained coats,” said one Union army surgeon. Surgeons stuck their ungloved fingers into wounds to feel for bullets. If they dropped a sponge or saw on the floor, they simply wiped it off with a cloth, or “washed” it in a basin of bloody water. As a result, about twenty-five percent of the soldiers who had an arm or leg amputated later died from infections.

S

oldiers who were lucky enough to avoid getting shot still faced the most dangerous killer of all in the Civil Warâdisease. Deadly diseases such as typhoid fever and dysentery spread through the camps of both Northern and Southern soldiers. By the time the war was over, twice as many men had died from disease as from battle wounds.

oldiers who were lucky enough to avoid getting shot still faced the most dangerous killer of all in the Civil Warâdisease. Deadly diseases such as typhoid fever and dysentery spread through the camps of both Northern and Southern soldiers. By the time the war was over, twice as many men had died from disease as from battle wounds.

A big part of the problem was the fact that army camps were often disgustingly dirty, allowing germs to spread quickly. For bathrooms, the men dug shallow, open ditches right near their tents. The ditches filled up quickly and got so gross that many of the men preferred to do their business elsewhere. A Virginia soldier found this out the hard way, as he wrote in his diary: “On rolling up my bed this morning I

found that I had been lying inâI won't say whatâsomething though that didn't smell like milk and peaches.”

found that I had been lying inâI won't say whatâsomething though that didn't smell like milk and peaches.”

Rotting food, animal manure, and dead animals also piled up all over camp. And this stuff seeped through the ground into streams and wells, polluting the water the soldiers drank. At one army camp, a newspaper reporter wrote, the water “smells so offensively that the men have to hold their noses while drinking it.” That can't be good for you.

The lack of personal cleanliness was another problem. Union army soldiers were supposed to wash their hands and face every day, their feet twice a week, and their whole body once a week. But not everyone did this. George H. Cadman from Ohio remembered that some of the men in his regiment were especially filthy, and “if not pretty sharply looked after would not wash themselves from week's end to week's end.

“There are two brothers who are especially dirty and if they are left alone for a few days they get such a coat of dirt upon their faces it is impossible to tell one from the other.”

Civil War soldiers were always short on soap, and many went weeks without washing or changing their clothes. “Soap seems to have given out entirely in the Confederacy,” said a Southern soldier. “I am without drawers [underwear] today, both pair of mine being so dirty that I can't stand them.” The Union soldier John Billings knew some men who remembered to change their underwear “at least once a week.” But others, he said, “would do so only under the severest pressure.”

One result of wearing dirty clothes was that Civil War soldiers fought a never-ending battle against body lice. Every night in camp, men sat around the fire picking lice off their clothes. The only way to really get rid of lice was to take off all your clothes and boil them in one of the kettles used for cooking food. But that was a lot of troubleâand the lice came back soon anyway.

Now you can understand why Civil War soldiers were often eager to leave camp, even if it meant marching into battle.

A

fter the disaster at Fredericksburg, Abraham Lincoln had no choice but to remove General Burnside from command. The war was going so badly that some people in the North were urging Lincoln to give up the fight. “We are now on the brink of destruction,” he said.

fter the disaster at Fredericksburg, Abraham Lincoln had no choice but to remove General Burnside from command. The war was going so badly that some people in the North were urging Lincoln to give up the fight. “We are now on the brink of destruction,” he said.

It was about to get worse.

Still searching for someone who could lead the Army of the Potomac to victories, Lincoln decided to give General Joseph Hooker a chance. Known to his men as “Fighting Joe,” Hooker boldly declared he would march right to Richmond.

“My plans are perfect, and when I start to carry them out, may God have mercy on General Lee, for I will have none.”

“Fighting Joe” Hooker

Lincoln winced when he heard such stupid statements. “That is the most depressing thing about Hooker,” he complained. “It seems to me that he is overconfident.”

Hooker had good reason to be confident, thoughâhe had about twice as many soldiers as Lee. In late April 1863 Hooker began marching his army through a thick Virginia forest known as the Wilderness. He camped near the town of Chancellorsville.

O

nce again, Robert E. Lee took a huge risk. According to the military textbooks Lee studied in college, when you have a smaller army than your enemy, you should keep all your soldiers together. Ignoring the rules, Lee divided his army into even smaller pieces. He gave a piece to Stonewall Jackson and told him to launch a surprise attack. “It must be victory or death,” Lee said.

nce again, Robert E. Lee took a huge risk. According to the military textbooks Lee studied in college, when you have a smaller army than your enemy, you should keep all your soldiers together. Ignoring the rules, Lee divided his army into even smaller pieces. He gave a piece to Stonewall Jackson and told him to launch a surprise attack. “It must be victory or death,” Lee said.

On the morning of May 2, Jackson led his men on a long march to get in position for the attack. “Press on, press forward!” he urged, as the army raced along narrow roads.

This was Hooker's big chanceâhe could have charged forward and crushed Lee's divided army. Instead, he just sat there. Later, when asked what had gone wrong, he said, “Well to tell the truth, I just lost confidence in Joe Hooker.” Bad timing, Joe.

At 5:15 that afternoon, Union soldiers were relaxing around their campfires, cooking dinner and playing cards. Then something very strange happenedâdozens of rabbits and deer suddenly burst out of the nearby woods and ran into the army camp. The men waved their hats and cheered the charging animals. That was the wrong reaction.

The reason those animals ran into the Union camp was that Stonewall Jackson's army was right behind them, driving them forward through the woods. Jackson's men charged into the Union camp, screaming the rebel yell. Startled Union soldiers were driven back into the woods.

What followed was part violent battle and part confusing chase through the forest. Whatever it was, Jackson was winning, and the fighting lasted until dark.

T

he battle of Chancellorsville continued the next morning, getting closer and closer to the Chancellor family house, which General Hooker was using as his headquarters. Fourteen-year-old Sue Chancellor, along with her mother and five sisters, dashed to the cellar for safety. Then a Union officer ran down and told them to get outâthe house was on fire!

he battle of Chancellorsville continued the next morning, getting closer and closer to the Chancellor family house, which General Hooker was using as his headquarters. Fourteen-year-old Sue Chancellor, along with her mother and five sisters, dashed to the cellar for safety. Then a Union officer ran down and told them to get outâthe house was on fire!

Sue scrambled out into the daylight and was met with a shocking scene. “The woods around the house were a sheet of fire,” she said. “Horses were running, rearing, and screaming, the men, a mass of confusion, moaning, cursing, and praying. Cannon were booming and missiles of death were flying in every direction ⦠. If anybody

thinks that a battle is an orderly attack of rows of men, I can tell them differently, for I have been there.”

thinks that a battle is an orderly attack of rows of men, I can tell them differently, for I have been there.”

Sue and her family retreated to a safer spot. So did “Fighting Joe” Hooker and most of his army. The battle of Chancellorsville was another crushing defeat for the Union.

“A

t Chancellorsville we gained another victory,” Lee said. “Our people were wild with delight.” But there was a dark side to the victory. “Our losses were severe,” Lee explained.

t Chancellorsville we gained another victory,” Lee said. “Our people were wild with delight.” But there was a dark side to the victory. “Our losses were severe,” Lee explained.

Lee's army lost about 13,000 men, compared with 17,000 for the Union. But remember, the South had a much smaller population than the North. So Lee knew he would have a much harder time replacing soldiers. He simply could not afford such bloody victories.

And the news got worse. The night after his successful surprise

attack, Stonewall Jackson was riding through the dark woods, planning the next day's action. A group of Confederate soldiers mistook him for a Union officer and fired, hitting Jackson in the right hand and left arm. Jackson was carried back to camp, where a surgeon amputated his shattered arm.

attack, Stonewall Jackson was riding through the dark woods, planning the next day's action. A group of Confederate soldiers mistook him for a Union officer and fired, hitting Jackson in the right hand and left arm. Jackson was carried back to camp, where a surgeon amputated his shattered arm.

Jackson was recovering from the operation when he developed pneumonia. It became clear that he was dying. Lee reacted strangely, refusing to visit Jacksonârefusing to face the fact that he was about to lose his best fighter. “He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right,” Lee said. “Tell him to make haste and get well, and come back to me as soon as he can.”

Anna Jackson was more realistic. She rushed to her husband's hospital bed. “His fearful wounds, his mutilated arm, the scratches on his face, and, above all, the desperate pneumonia ⦔ she said, “wrung my soul with such grief and anguish as it had never before experienced.”

When Stonewall asked Anna how he was doing, Anna spoke the harsh truth. Stonewall called over Dr. Hunter McGuire.

“Doctor,” he said. “Anna informs me that you have told her I am to die today. Is it so?”

Dr. McGuire nodded.

“It is all right. It is the Lord's day,” Jackson said. “I always desired to die on Sunday.”

Soon he began drifting into dreams, calling out battle orders to his generals: “Order A.P. Hill to prepare for action!” Then he smiled and quietly said, “Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees.” Then he died.

Jefferson Davis declared a national day of mourning throughout the South.

Other books

Suddenly Sorceress by Erica Lucke Dean

Herb-Wife (Lord Alchemist Duology) by McCoy, Elizabeth

Harrison Squared by Daryl Gregory

Clandara by Evelyn Anthony

Booty Bones: A Sarah Booth Delaney Mystery by Carolyn Haines

Down to the Sea by William R. Forstchen

August: Osage County by Letts, Tracy

Jakarta Pandemic, The by Konkoly, Steven

A Week in New York (The Empire State Series Book 1) by Bay, Louise