Two Miserable Presidents (10 page)

Read Two Miserable Presidents Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

T

hrough the rainy, muddy May of 1862, McClellan's army continued pushing forward. By late May, Union forces were just six miles from Richmond. They could see the city's church steeples and hear the clocks striking. The men cheered when Mac visited them:

hrough the rainy, muddy May of 1862, McClellan's army continued pushing forward. By late May, Union forces were just six miles from Richmond. They could see the city's church steeples and hear the clocks striking. The men cheered when Mac visited them:

McClellan:

How do you feel, boys?

How do you feel, boys?

Soldiers:

We feel bully, General!

We feel bully, General!

McClellan:

Do you think anything can stop you from going to Richmond?

Do you think anything can stop you from going to Richmond?

Soldiers:

No! No!

No! No!

Robert E. Lee disagreed.

With his polite manners, his white hair, and his glasses, Robert E. Lee didn't seem like a warrior. In fact, some folks in Richmond had taken to calling him “Granny Lee” (behind his back, of course). But soldiers who knew Lee painted a very different picture. As one Confederate officer said: “He will take more chances, and take them quicker, than any other general in this country, North or South.”

Step one for Lee was to find out exactly where the enemy army was. He didn't have balloons, but he did have Jeb Stuart, a twenty-nine-year-old cavalry officer with a giant cinnamon-colored beard and a foot-long ostrich feather in his hat. Eager for action and fame, Stuart gladly accepted the dangerous mission of riding out and locating McClellan's army.

“And if I find the way open, it may be that I can ride all the way around him. Circle his whole army.

Jeb Stuart

And that's exactly what he did. Stuart led 1,200 men on a three-day, hundred-mile ride around McClellan's entire army. Losing just one man, Stuart's force burned wagons full of Union supplies and brought back hundreds of Union prisoners. Stuart got famous. McClellan got embarrassed. And Lee got the information he needed.

Then, in a series of brutal battles known as the Seven Days, Lee attacked McClellan every day for a week. “Come on; come on, my men! Do you want to live forever?” shouted a Confederate officer to his charging soldiers. The Union soldiers staggered backwards, fighting their guts out but steadily losing ground. The casualties were enormousâa total of more than 30,000 Union and Confederate soldiers were killed or wounded. And though Lee lost even more men than McClellan, Seven Days was a major Confederate victory. The Union army had been driven far from Richmond.

When the fighting ended, survivors on both sides tried to put the weeklong bloodbath behind them. One Southern soldier remembered: “Our boys and the Yanks made a bargain not to fire at each other, and went out in the field ⦠and gathered berries together and

talked over the fight, traded tobacco and coffee and exchanged newspapers as peacefully and kindly as if they had not been engaged for the last seven days in butchering each other.”

talked over the fight, traded tobacco and coffee and exchanged newspapers as peacefully and kindly as if they had not been engaged for the last seven days in butchering each other.”

A

braham Lincoln was in no mood to pick berries. The entire North was disappointed and angry, and Lincoln got most of the blame. He desperately wanted to fire McClellan, but he was afraid the soldiers would be angry. “McClellan has the army with him,” Lincoln said.

braham Lincoln was in no mood to pick berries. The entire North was disappointed and angry, and Lincoln got most of the blame. He desperately wanted to fire McClellan, but he was afraid the soldiers would be angry. “McClellan has the army with him,” Lincoln said.

Then there was the always explosive issue of slavery. Abolitionists such as Frederick Douglass were demanding that Lincoln attack Southern slavery as well as Southern armies.

“To fight against slaveholders, without fighting against slavery, is but a half-hearted business.”

Frederick Douglass

Douglass was making an interesting point about war strategy. Southern farms and businesses depended on the labor of enslaved African Americans. And the Southern army was using slaves to build forts and cook food. Slavery was actually helping the South fight the war. So freeing slaves could help the North win it.

Lincoln agreed with Douglass's logic. When asked about ending slavery, he said, “I can assure you that the subject is on my mind, by day and night, more than any other.”

One of the questions on Lincoln's worried mind was this: If the Confederacy's 3.5 million slaves were freed, where would they live? Lincoln was considering an idea some politicians were suggestingâthat freed slaves should move to another country, maybe in Central America. But black leaders came to the White House to urge Lincoln to put that stupid idea out of his mind. As Robert Purvis told the president: “In the matter of rights, there is but one race, and that is the human race ⦠. Sir, this is our country as much as it is yours, and we will not leave it.”

Lincoln was also nervous about the four “border states,” or slave states that were still in the Union: Missouri, Kentucky, Maryland, and Delaware. If he tried to abolish slavery, would those states join the Confederacy?

And here's another question: Shouldn't free African Americans be allowed to enlist in the Union army? As of the middle of 1862, this was still being debated in Congress.

Some people weren't waiting for Congress to make up its mind.

R

obert Smalls was a twenty-three-year-old expert boat pilot in Charleston, South Carolina. He was also a slave. In 1862, Smalls was working on the

Planter

, an armed steamship used by the Confederate navy.

obert Smalls was a twenty-three-year-old expert boat pilot in Charleston, South Carolina. He was also a slave. In 1862, Smalls was working on the

Planter

, an armed steamship used by the Confederate navy.

On the night of May 12, the

Planter

was loaded with weapons and ammunition. The captain told Smalls to have the ship ready for an early departure the next morning.

Planter

was loaded with weapons and ammunition. The captain told Smalls to have the ship ready for an early departure the next morning.

“Aye, aye, sir,” Smalls said.

The captain and white crew went on shore for the night, leaving on board Smalls and the other black crew members. The captain never would have guessed that Smalls and the black crew, all slaves, had spent the past few months preparing for this exact moment.

At three a.m. on May 13, Smalls put on the captain's hat and jacket. He powered up the steam engines and began cruisingâvery slowly, as if this were just another normal night. At a dark waterside spot he stopped to pick up his wife and children, as well as family members of the other crew members. Then he turned the ship and headed out to sea.

Now came the most dangerous part of the escape: the Planter had to sail right past five Confederate forts in the harbor. To pass each fort, a ship had to blow a different secret signal on its steam whistle. Smalls knew these signals, but if anything went wrong, he and the crew had agreed, they would never allow themselves to be taken alive. If stopped, they would blow the ship into the sky.

Smalls hunched over and paced back and forth exactly as the

Planter's

captain normally did. Smalls had practiced this walk, and in the dark, from a distance, he looked like the captain. As the ship passed each fort, Smalls blew all the right signals on the ship's

whistle. At 4:15, just as the sun was beginning to rise, the

Planter

reached Fort Sumter, the last fort. Smalls blew the secret signal.

Planter's

captain normally did. Smalls had practiced this walk, and in the dark, from a distance, he looked like the captain. As the ship passed each fort, Smalls blew all the right signals on the ship's

whistle. At 4:15, just as the sun was beginning to rise, the

Planter

reached Fort Sumter, the last fort. Smalls blew the secret signal.

“Pass!” yelled the guard.

Safely beyond the fort, Smalls ran a white flag (the signal of truce or surrender) up the ship's flagpole and sailed toward a group of Union ships floating about three miles out. As the

Planter

cruised closer, Union sailors were shocked to see a Confederate ship with an all-black crew. A Union captain demanded to speak with the

Planter

's captain.

Planter

cruised closer, Union sailors were shocked to see a Confederate ship with an all-black crew. A Union captain demanded to speak with the

Planter

's captain.

You're speaking with him now, Robert Smalls told them. “I have the honor, sir, to present the

Planter.”

Planter.”

Robert Smalls's dash to freedom was a massive front-page story all over the North and South. It was “one of the most daring and heroic adventures” of the war, declared the

New York Herald

. The Union gained a valuable ship, full of supplies. And Smalls became a symbol in the debate over emancipation. To many Northerners, Smalls's actions made it more obvious than ever that all African Americans should be free.

New York Herald

. The Union gained a valuable ship, full of supplies. And Smalls became a symbol in the debate over emancipation. To many Northerners, Smalls's actions made it more obvious than ever that all African Americans should be free.

I

n a meeting with his cabinet on July 22, 1862, Lincoln announced an important decision. He was going to declare all slaves in the Confederacy free.

n a meeting with his cabinet on July 22, 1862, Lincoln announced an important decision. He was going to declare all slaves in the Confederacy free.

Once they got over the shock, most of Lincoln's advisors supported the idea. But the secretary of state, William Seward, raised a concern. If they issued this plan now, when the war was going so badly for them, wouldn't they look kind of weak and desperate? Wouldn't it be better to wait for a military victory?

Good point, Lincoln said. He put the Emancipation Proclamation back in his desk.

In August there was another big battle near Bull Run in Virginia. Lee and Jackson crushed a large Northern force, sending the Union army stumbling back toward Washington.

“Well, John, we are whipped again, I'm afraid,” Lincoln told his secretary. And that proclamation stayed in his desk.

R

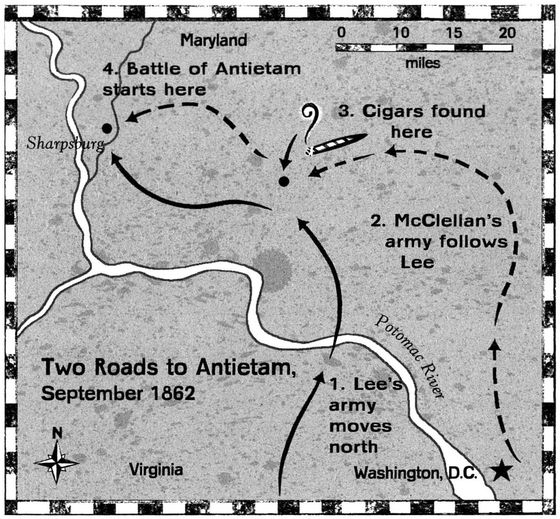

emember that quote about Robert E. Lee taking chances? On September 4, Lee's army waded into the Potomac River and splashed across the shallow water to Maryland. Lee was invading the North.

emember that quote about Robert E. Lee taking chances? On September 4, Lee's army waded into the Potomac River and splashed across the shallow water to Maryland. Lee was invading the North.

Lee knew he could lose everythingâhis entire army, and the war too. But he also knew he could win everything. One huge victory on Northern territory just might convince the North that it could never win this war. The South would have its independence.

There was only one problem, as Lee told Jefferson Davis, “The army is not properly equipped for an invasion of an enemy's territory.”

That was putting it mildly. Thousands of Lee's soldiers were barefoot. Their clothes and bodies were so filthy, people in Maryland said they smelled the army before they saw it. One witness called them “the dirtiest men I ever saw, a most ragged, lean, and hungry set of wolves.” Lee's half-starved soldiers picked unripe apples and corn, and soon thousands of men were sprinting into the woods, sick with diarrhea.

Still, Lee's soldiers continued marching north in high spirits. These were tough combat veterans who were used to winning.

Then, in a war full of incredible events, something truly unbelievable happened.

A

few days after Lee's army marched through Frederick, Maryland, the Union army began to arrive. At about ten in the morning on September 13, a group of Indiana soldiers sat down to grab a quick rest. Corporal Barton Mitchell was sitting under a tree when he noticed a piece of paper lying in the grass a few feet away. He picked up the paper and found that it was wrapped around three cigars. Barton was thrilledâhe sent his friend for matches to light the cigars. Then he unrolled the piece of paper. “As I read, each line became more interesting,” he said. “I forgot those cigars.”

few days after Lee's army marched through Frederick, Maryland, the Union army began to arrive. At about ten in the morning on September 13, a group of Indiana soldiers sat down to grab a quick rest. Corporal Barton Mitchell was sitting under a tree when he noticed a piece of paper lying in the grass a few feet away. He picked up the paper and found that it was wrapped around three cigars. Barton was thrilledâhe sent his friend for matches to light the cigars. Then he unrolled the piece of paper. “As I read, each line became more interesting,” he said. “I forgot those cigars.”

Special Orders, No. 191

Headquarters Army of Northern Virginia

⦠The army will resume its march

tomorrow, taking the Hagerstown road.

General Jackson's command will form

the advance â¦

Headquarters Army of Northern Virginia

⦠The army will resume its march

tomorrow, taking the Hagerstown road.

General Jackson's command will form

the advance â¦

This was General Lee's entire plan! Some careless Southern officer must have wrapped a copy of the plan around his cigars and dropped it there by accident. The letter described exactly where each part of Lee's army was and where they were headed. And best of all, it showed that Lee's army was spread out all over the placeâcompletely unprepared for battle.

“Now I know what to do!” shouted McClellan when he saw the letter. “Here is a paper with which, if I cannot whip Bobby Lee, I will be willing to go home.”

Southern spies told Lee that McClellan had his plans. Lee rushed messages to all his commanders to gather as quickly as possible at a town called Sharpsburg. When Lee got there he pointed to the high ground above Antietam Creek and said, “We will make our stand on these hills.”

McClellan, meanwhile, moved so slowly that he missed a golden opportunity to attack before Lee was ready. By September 17, Lee had about 40,000 soldiers at Antietam Creek. Little Mac had about 80,000.

Families hid in their cellars and frightened farmers cleared their cows and horses from the fields.

Other books

Fraternization Rule (Risqué Contracts Book 3) by Fiona Davenport

True Fires by Susan Carol McCarthy

Joint Enterprise (The Romney and Marsh Files Book 3) by Oliver Tidy

The Ferryman by Amy Neftzger

The Free (P.S.) by Vlautin, Willy

Face-Off by Matt Christopher

The Future We Left Behind by Mike A. Lancaster

BILLIONAIRE (Part 5) by Jones, Juliette

Fault Lines by Brenda Ortega

Ravaged Land - A Post-Apocalyptic Novel by Kellee L. Greene