Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (132 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Josh:

I told you no real baseball fans would behave this civilly of their own volition.

Kevin:

Start working on your excuses for infractions 1, 2, 5, 6 and 7.

If you see a guy with more than 200 Mariner Moose plush toys strung around his neck, you’ve found The Moose Man. Yeah, he’s not too hard to find. The Moose Man has been adding to his soft collection ever since he attended his first game at Safeco, and thinks that each time he buys one, he’s buying the M’s a bit of good luck. The Moose Man is very approachable and loves being asked to have his picture taken.

Lorin “Big Lo” Sandretzky gets our nod for the super-est of the super-fans in town, not only for his support of the Mariners, but of all Seattle sports teams. This crazy gent is famous for greeting Seattle’s pro teams at the airport when they return from the road. “Big Lo” is tough to miss, at six feet eight inches tall and more than 450 pounds. He’s even received his own action figure. Look for “Big Lo” in section 142, along the third-base line.

Cyber Super-Fans

- USS Mariner

- Jason Churchill at Prospect Insider

- Lookout Landing

Rick “The Peanut Man” Kaminsky was still tossing peanuts to Mariners fans well into his 70s. But, sadly, he passed away in 2011 and will be missed as an essential part of the Seattle baseball experience. Ever since the Kingdome opened in 1977, Crazy Peanut Guy had made an art form out of his profession. Though he looked like a brown-haired Harpo Marx, Crazy Peanut Guy was still an ace who rarely, if ever, missed in his tosses of bags of hot salted nuts. Before he passed away, he became a YouTube sensation and he even had a Facebook page.

There is, and forever will be, only one voice in the ears of Mariner fans. And that golden throat belongs to Mr. Dave Niehaus, the Mariners’ number one fan. Dave Niehaus’s voice, his passion, his sheer and unwavering love for the Mariners, and the unique and wonderful way he expressed that love in clever phrasings, is the very reason many Seattleites became Mariner fans. He is honored in the Mariner Hall of Fame inside the ballpark, and outside as well, with his own statue. The city and the sport of baseball owe a debt of gratitude to Dave Niehaus that simply can never be repaid. He was one of a kind—and he loved the Mariners with his entire heart.

Sports in the City

Sick’s Stadium

2700 Rainier Ave. South

We don’t necessarily recommend it, but fanatics of bygone Seattle sports might consider visiting the site of old Sick’s Stadium (and Dougdale Park prior), which was home to the American League’s short-lived Seattle Pilots. The Pacific Coast League’s Rainiers played at Sick’s, too, as did the West Coast Baseball Association’s Seattle Steelheads, a well-named Negro League team that—like the Pilots—played just one season (1946) in Seattle. It was a beautifully clunky little park that hosted outdoor baseball in Seattle for more than eighty years. But it was woefully small and inadequate for big league play.

Those who embark upon this somber pilgrimage will find a large chain hardware store where Sick’s Stadium once stood. It’s enough to break your heart. Inside the store there is a glass display featuring Pilots’ and Rainiers’ memorabilia.

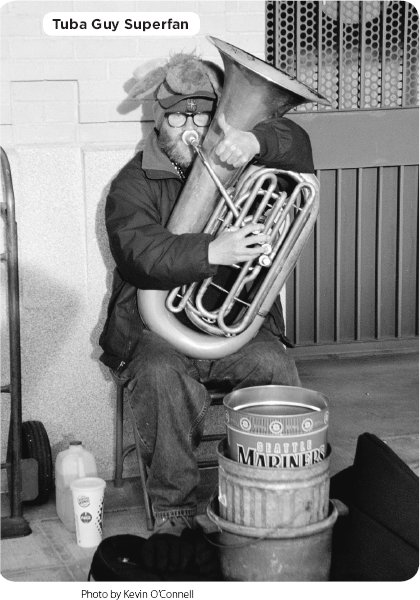

Edward Scott McMichael was the Tuba Man, and we want to honor him. In more than three decades, Tuba Man rarely missed a major sporting event in the greater Seattle area, puffing away on his instrument like the professional he was. He was an odd-looking man, a gentle giant, rather hairy, and decked out from head to toe in Seattle sports paraphernalia. And boy, oh boy, could Tuba Man blow his horn. Any song you want, he’d play it. All with a cheerful smile and warm thumbs-up.

A visit to the ballpark in Seattle simply was not complete unless you heard Tuba Man’s low tones rumbling as you hurried toward the gates. Unfortunately, Tuba Man was assaulted by some street toughs, badly beaten, and later died from the injuries he incurred. The outpouring of grief from the city was tremendous. Few people in life have such a wonderful effect on so many. Tuba Man was well loved and will be missed.

Bill “The Beer Man” Scott used to be an actual beer man at the Kingdome who took breaks from peddling foam to lead

the crowd in cheers. He quickly became a minor celebrity and quit sloshing suds to lead the crowd in cheers full time for the M’s, Seahawks, Sonics, and Huskies, but passed away in 2007.

We Almost Won the Whole Damned Thing

After a beautiful day of outdoor baseball, highlighted by a 16-4 Mariners win over Detroit, we decided to look for some “action.” Because we’re both married, we decided against a singles bar and instead headed for Sluggers, where we logged onto the daily nationwide satellite trivia game. After lengthy debate, we settled on “The Baseball Boys” as our team name. If you were online that August night, chances are you’ll remember our legendary run.

After fumbling with the controller for a round, we were damned near “unconscious,” nailing question after question, as other patrons began to take note and marvel at our cumulative wealth of obscure—and for the most part, useless—knowledge.

Josh carried the team early thanks to his remarkable knowledge of the atlas. Who knows where Timbuktu is, specifically? Josh does. He’s also great with numbers. Did we mention that? And Kevin’s knowledge of all-things-nautical scored major points during a prolonged string of submarine queries. Just when it looked like things couldn’t get any better, the waitress brought over a free round of brews, compliments of the house. Buoyed by a fresh lager, Kevin ran the table on an

Ancient World History

category as the growing crowd around our table cheered him on. The way he carefully enunciated each answer—“Hieronymus of Cardia, historian and statesman of ancient Greece who chronicled the life of Alexander the Great”—made Josh wonder if his friend was channeling the spirit of living trivia deity Alex Trebek.

The crowd roared. Josh beamed. And Kevin channeled.

But then tragically, a full day’s worth of hot dogs, microbrews, Ichi-rolls, and garlic fries, came crashing down around us. After building a lead of 2,500 points—nationwide, mind you—we flailed miserably (picture Gorman Thomas trying to hit a curveball) at the next eleven questions. A

Cheeses of the World

category brought us to our knees. Kevin kept saying “Munster,” and Josh kept keying it in. From havarti to gorgonzola, neufchatel, brie, and cheddar, all other cheeses came up on the screen, but never Muenster.

“Damn,” Kevin said. “I could have sworn that last one was Munster.”

“You’re blowing it,” Josh barked. “If we don’t nail the next question, I swear to God, you’re walking to San Francisco to eat garlic and cheese fries by yourself.”

“Whatever,” Kevin chortled. “The rental car’s in

my

name.”

The next category,

Famous Confederate Horses of the Civil War,

focused not surprisingly on the equines who reached rock star status in the day of our forefathers. When the question came, we were ready for it.

What was the name of the battle steed killed at Perryville while being ridden by Major General Patrick Cleburne?

After a long and thoughtful pause, Kevin answered the anxious stares of Josh and others with an uncertain, “Munster?”

The answer turned out to be

Dixie

. Our huge lead having evaporated, we entered the last round tied for first with

a team of Cleveland yahoos who called themselves “A Tribe Called Jest.”

Fate was in our corner as the last question came, coincidentally enough, straight out of the Seattle Mariners archives.

“Which Mariners player kneeled down on the carpeted Kingdome floor on May 27, 1981, and tried to blow a dribbler down the third-base line foul?”

The relieved smile on Kevin’s face made it clear that he knew the answer. Josh pumped his fist in the air and made a “raise-the-roof” gesture to the crowd, which had more or less lost interest by this point since the barman had just announced “last call.”

“Come on, people,” Josh yelled. “We’re about to claim our rightful place as the most knowledgeable drunken trivia team in all of America.” Then, as he turned to Kevin for the winning answer—(D) Lenny Randle—in his excitement he knocked over Kevin’s pint of beer, spilling it on the control pad. Kevin kept hitting the D button, but it was no use. A Tribe Called Jest had already answered.

Kevin blamed Josh for the goof, and Josh blamed Kevin for leaving his beer so close to the controller. For a few minutes, tensions ran high. But when the waitress sauntered over with another free round, and the crowd burst into a mixture of applause and jeering laughter, we buried the hatchet and stumbled out the door as best of friends again.

OAKLAND ATHLETICS,

OAKLAND ATHLETICS,O.CO COLISEUM

Overdue for Replacement in Oak-Town

O

AKLAND

, C

ALIFORNIA

17 MILES TO SAN FRANCISCO

365 MILES TO LOS ANGELES

739 MILES TO PHOENIX

810 MILES TO SEATTLE

I

f we were betting men, and if the bookies took wagers on things like which ballparks would be replaced and how soon, then after our first baseball road trip back in 2003, we would have bet the farm that by the time a second edition of this book became necessary, the Grand Old Game would have deserted the cavernous football stadium to be re-named later in Oakland for cozier, more baseball-friendly pastures. Either that, or they would have left Oak-Town altogether. See, back then the money-balling A’s were the talk of the game as they continued to compete for the American League pennant each year despite possessing a payroll a fraction the size of their peers’. In fact, when

The Ultimate Baseball Road Trip

hit bookstore shelves in early 2004, the A’s were riding a four-year playoff run. Despite the team’s success, though, there were ominous signs that this franchise that had long played second fiddle to the San Francisco Giants would soon be venturing into troubled waters if it didn’t resolve its stadium situation. And indeed, while the Giants have flourished on and off the field in a beautiful waterfront park, attendance at the concrete behemoth in Oakland has tailed off precipitously.

When A’s general manager Billy Beane’s boys ran out of magic, the A’s plummeted to the bottom of MLB’s attendance barrel. And hey, let’s face it: Their games really weren’t that well attended even when they were winning. By the time of this revision’s print date, the A’s had been struggling to draw twenty thousand fans per game for several years. Everyone seems to agree a new ballpark is necessary for the storied Athletics franchise, but they can’t agree on where to put it. For more than a decade the topic has been debated. Various plans involving various sites have been explored and then abandoned, shattering fans’ hopes. As a final insult to the green-and-gold-clad rooters still following the A’s, the football stadium in which they play has embarrassingly been named and renamed and renamed again, ad nauseam, to the tune of six name changes since 1998. In April 2011 it adopted the handle Overstock.com Coliseum, then two months later, when Overstock.com announced it would be changing its corporate name to O.co, it adopted the abbreviated company name as its own. Before that it was the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum (2008–2011), McAfee Coliseum (2004–2008), Network Associates Coliseum (1998–2004) and the Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum (1966–1998). It was also briefly called UMAX Technologies Coliseum back in 1997, but that naming rights deal dissolved amidst a legal dispute before the field could see any action for baseball.

One thing is certain: The A’s need a new

baseball

park if they’re going to compete in the modern game. Preferably for locals that park would sit somewhere inside the Oakland limits or close by, but among the ideas to reinvigorate the A’s have been serious proposals to move them to San Jose, Fremont and even Las Vegas. At the time of this writing, the most likely destination for the A’s appeared to be San Jose, where a deal to build a thirty-two-thousand-seat, $400 million park and name it Cisco Field was coming closer to fruition. The proposal, which called for the new baseball-only facility to be completed in time for the 2015 season, still faced many hurdles, though. At the top of the list, the A’s and their owner Lew Wolff still needed the Giants to rescind their exclusive territorial rights to Santa Clara County. Whether this is the new home for the A’s or whether it’s just the latest in a series of possibilities that eventually fall apart, we can’t say. But let us repeat: The A’s need a new park.

Kevin:

Three words: Jack. London. Square.

Josh:

Succinct. To the point. Great location. Authorly. I like it.

With an exterior consisting of lots and lots of cement and some grassy slopes, the O.co makes an awkward impression right from the start. Plopped down in the middle of a sports complex, surrounded by asphalt and industrial warehouses, we suppose it didn’t have much of a chance.

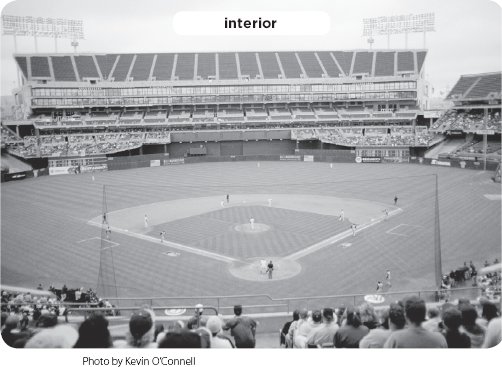

There is little of the awe here that Yankee Stadium inspires, the charm that Oriole Park projects, or the intimacy that Wrigley Field holds. Completely round when it was originally constructed, this ballfield twenty-one feet below sea level, has become a paradise for pitchers. The circular shape of the seating bowl best accommodates a football gridiron, not baseball diamond, and results in the most expansive foul territory in the majors. The cool night air combines with the large field to stifle the prospects of the homers today’s fans so love. Indeed, everything about the O.co is large. The stadium accommodates more than sixty-three thousand Raiders fans during football season, but when the A’s are playing the stadium staff unrolls large green tarps to cover massive swaths of the upper deck. As a result, instead of playing home games before twenty thousand fans and forty thousand empty seats, the A’s play before twenty thousand fans, fifteen thousand empty seats, and a shiny plastic sheet. If this is an improvement, it is only a slight one.

Kevin:

Green tarps cost a heck of a lot less than new ballparks.

Josh:

They were on sale at Lowe’s last week.

Kevin:

They might be calling this dump the Lowe’s Coliseum by the time we leave.

Despite the A’s success during the Billy Beane years in building rosters around solid pitching and defense, with just a enough hitting to edge the opposition, during their earlier days the A’s better teams were characterized by rough-and-ready hitters, guys like Reggie Jackson, Rickey Henderson, Jose Canseco, Mark McGwire, Eric Chavez, and Jason Giambi. Perhaps this is because the club plays in Oak-Town, a rough-and-ready city that’s full of blue-collar—perhaps we should say “green-collar”—folks. While the dot-com boom of the 1990s gentrified sections of the East Bay, Oakland remained at its core a no-nonsense place. In this regard, we suppose, the O.co is a reflection of the city in which it resides. It does very little to please the eye, nor does it project the impression it is trying very hard. As visitors cross the chain-link fence lined pedestrian bridge from the BART station to the stadium, the landscape below is industrial, showcasing wooden shipping pallets, lumber, railroad tracks, and a backwater slough. Though it may not be the most attractive ballpark entrance, it is perhaps the most congruent with the stadium it presages. The O.co is an ode to cement and green plastic.

Built to serve the Oakland Raiders, as well as to potentially lure the A’s from Kansas City, Oakland-Alameda County Coliseum, as it was originally known, opened for football in 1966. The City of Oakland and Alameda County have remained its owners ever since. Charlie O. Finley, who had failed in his bid to move the Kansas City A’s to Arlington, Texas, in 1962, took his club to Oakland in 1968. Seattle was also considered by Finley as a possible destination for his A’s, but Oakland got the nod since it already had the Coliseum ready and waiting. The O.co had been designed by architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill and built at an original cost of $25.5 million. The multi-use stadium anchored a complex that would include an exhibition hall and the basketball gym once known as Oakland Arena—now Oracle Arena—that has served the NBA’s Golden State Warriors since 1966.

During their five decades in Oakland, the A’s have been a colorful, hard-scrabble bunch. Think of the “Mustache Gang” of the early 1970s that won five straight AL West titles (1971–1975) and three straight World Series (1972–1974). Those guys fit the attitude of the city well. You couldn’t picture them eating caviar at a trendy downtown restaurant or sitting down for a snifter of brandy in an elegant hotel ballroom. Guys like Catfish Hunter, Vida Blue, Rollie Fingers, Sal Bando, and Joe Rudi played hard-nosed ball that made them heroes to the working class who rooted them on.

Sure, Jackson was on the team too, but he was a lone starlet and that was long before his head really swelled as he arrived in New York and pronounced he owned the place. Mr. October notwithstanding, those guys were dirt-dogs who played like their lives depended on it. They went to the park and got to work as if baseball was their job. Come to think of it, it

was

their job. And they attacked other teams the way a mechanic dismantles a manifold.

Before that glorious run for the fighting A’s of the ’70s, fans in the Bay Area hadn’t taken much interest in the team. Afterwards, they were hooked. It took six seasons before the A’s cracked the one-million mark in attendance, and that was with Finley at the helm, one of the most promotion-happy head honchos in big league history. But Finley wasn’t always the most popular guy in Oakland. He could be a pennypincher and when he sold off the “Swinging A’s” of the ’70s, some local rooters vowed never to forgive him. Today, the A’s, who won three straight World Series, are rarely mentioned in discussions of greatest dynasties. We’re not sure why.

Josh:

Name the other franchise that’s three-peated.

Kevin:

You mean there’s only one other?

Josh:

But they’ve done it three times.

Kevin:

Oh, right, the Yankees.

Josh:

They won between 1998 and 2000, 1949 and 1953, and 1936 and 1939.

Kevin:

Whoop-de-do for them. Do we owe Pat Riley money for saying three-peat?

By the late 1970s the A’s were again less than competitive as they finished in last place in 1977, next to last in 1978, and then last again in 1979. The Green and Gold failed to win seventy games in any of those seasons. When the scoreboard went black one day, the nearly empty concrete Coliseum took on the nickname “the Mausoleum.” The Bay Area’s own Billy Martin, who had grown up in Berkeley, took over the managerial reins in 1980 and brought to town a brand of play dubbed “Billy Ball” that would characterize the next era. “Billy Ball” was an NL style of play. Aggressive base-runners and strong pitchers who could go all nine became the trademarks of Martin’s pugilistic squad. But the toll taken on sore-armed pitchers had its downside, as numerous prospects blew out their arms.

The return to glory for the A’s was enabled by a strong farm system and some chemical help. The renaissance began in 1986 when the admittedly juicing Canseco hit thirty-three home runs on the way to claiming AL Rookie of the Year honors. The next season, fellow user McGwire kept the ROY in Oakland, bashing forty-nine long balls. In 1988 an A’s player won the ROY for the third straight year when shortstop Walt Weiss took the trophy. McGwire and Canseco became “the Bash Brothers,” and along with teammates Rickey Henderson and Dave Henderson, led the A’s back to postseason play.

While these sluggers paced the offense, A’s manager Tony La Russa was hard at work redefining how to utilize a pitching staff in the modern day. He introduced the one-inning closer in 1988 when he used Dennis Eckersley for the ninth inning and the ninth inning only. Each setup man knew his role—his inning—and La Russa rarely deviated from the script. Now it’s common for each team to have a closer, an eighth-inning guy, a seventh-inning guy, a lefty-specialist and so on, thanks to La Russa’s vision and the success it enabled.

As the A’s evolved, so too did their stadium. And no discussion of that evolution would be complete without acknowledging the role the Raiders played in reshaping the contours of the Coliseum. After Raiders owner Al Davis devastated the city when he moved the Silver and Black out of Oakland in 1981, heading for the Los Angeles Coliseum, the Raiders’ twelve-year southern hiatus left an enormous hole in the hearts of Oakland’s costumed fans. And so, in an effort to lure their Raiders back, Oakland began a reconstruction of the Coliseum in 1995. The baseball-friendly outfield bleachers were replaced with a massive four-tier seating and luxury box structure that has come to be known derogatorily as “Mount Davis.” A total of ten thousand upper-deck seats were added, all of which are tarped over during baseball season. Also added were two giant clubhouses, 125 luxury suites, a nine-thousand-square-foot kitchen, two new color video boards, and two matrix scoreboards in the end zones. The price of the undertaking was supposed to check in at $100 million, but swelled to double that.