Ultimate Baseball Road Trip (98 page)

Read Ultimate Baseball Road Trip Online

Authors: Josh Pahigian,Kevin O’Connell

Kevin:

When did it become hip to smash together two words like FiveSeven?

Josh:

Probably around the time folks stopped using the word “hip.”

Glasses of wine are available at a stand on the level left-field concourse. Daiquiris, frozen and fruity, are also available throughout the park. As for beer, twenty-four-ounce bottles of Corona and Dos Equis are unique to Houston. On tap, Shiner Bock and Shiner Blonde are the local choices. Kevin tried the Bock and called it “microbrew for beginners.”

Like the food at Minute Maid, we found the Astros fans we encountered had vastly upped their game upon our return. A higher percentage of fans wore the team colors than when we previously visited—Kevin speculated that they stocked up during the 2005 World Series run—and they made a lot more noise. We couldn’t help but feel that the city, which has been in the bigs for a long time now, had finally come into its own.

After singing “Take Me Out to the Ball Game,” the Astros play “Deep in the Heart of Texas” over the P.A. system and a handful of fans join in. So be prepared to carry your section.

It starts like this:

The stars at night—are big and bright

Deep in the heart of Texas.

The prairie sky—is wide and high

Deep in the heart of Texas.

The Sage in bloom—is like perfume

Deep in the heart of Texas.

Don’t sketch out when the person performing the National Anthem gets to “the rockets’ red glare,” and fireworks come shooting out of left field—even when the roof is closed. Indoor fireworks are legal in Texas.

Bring your binoculars if you fancy yourself a bird-watcher because we observed plenty of feathered friends flying inside Minute Maid, even though the roof was closed.

Kevin:

Hey, birds are better than flying bats, right?

Josh:

The folks in Port St. Lucie, Florida might not agree.

Kevin:

Say what?

Josh:

The Mets’ spring training park there has a bat house on site. And the little critters help maintain the mosquito population.

Kevin:

Oh. I thought we were talking about baseball bats.

Cyber Super-Fans

We recommend these excellent Astros fan sites, which are both as cleverly named as they are informative.

- Crawfish Boxes

www.crawfishboxes.com/ - Climbing Tal’s Hill

http://climbingtalshill.com/

If you find yourself getting a little shaggy after so many weeks on the road, you can get a haircut while watching the game courtesy of Sport Clips, which operates several chairs overlooking the field on the left-field concourse. These seats reminded us of Midway Stadium in St. Paul, Minnesota, where fans of the American Association Saints were treated for years to haircuts courtesy of an aged nun. Fear not: In Houston, perky young stylists more along the lines of the ones you’d find at Super Cuts do the shearing while you don’t miss a single pitch.

A board in right field displays the text of everything the stadium P.A. announcer says.

Available for free throughout the ballpark, Wi-Fi enables fans to search the web while (sort of) watching the game.

Sports in the City

The Houston Astrodome

We took a drive to check out the Eighth Wonder of the World, which stands across the street from a Six Flags Over Texas amusement park, southwest of the Interstate 610 loop that circles Houston.

Expecting to be blown away by the size of the legendary dome, we were disappointed to find it currently dwarfed by Reliant Stadium, which is right beside it. Reliant, home of the NFL Texans, sits in a larger footprint than the dome and rises quite a bit higher. The football field, which opened in 2002, was the NFL’s first retractable-roof gridiron.

Josh:

Hey, why not buy the Kindle version of our book while you’re trying to decide what to order for ballpark food?

Kevin:

That’s some shameless self-promotion right there.

Josh:

When did I ever admit to having an ounce of shame?

We Witnessed the Birth of the Third Inning Stretch

Unbeknownst to us, when we plopped down in Row 25 of the Dugout Seats, we were just 24 rows behind former President George H.W. Bush and his lovely mother, um, we mean wife, Barbara, as well as aviation legend Chuck Yeager, and a whole gaggle of Secret Service agents.

Once the game began, Kevin headed upstairs to snap some pictures from the upper deck. He hadn’t been in Section 419 for two minutes when a ballpark security guard approached and began brusquely interrogating him.

“Excuse me, sir,” the uniformed officer said from the concourse below. “I need you to come down here so I can have a word with you.”

Kevin, a wannabe hippie at heart, is not always the most eager person in the world to readily comply with law enforcement, but went along. When he reached the lower level, the eager young officer looked him over from behind mirrored sunglasses as he worked a toothpick back and forth from one side of his mouth to the other.

“How do you feel about our former president?” the man finally asked.

“Excuse me?” Kevin replied.

“Oh, you heard me,” the man snapped. Now, Kevin had heard the man just fine. It’s just that he didn’t think the officer would very much enjoy hearing the truth about his feelings about the former president, and he feared how the officer might react to such feelings.

He then looked Kevin over again, as the toothpick ping-ponged from side to side. He asked Kevin why he was taking pictures and was occasionally speaking into a microcassette recorder.

Kevin explained that the pictures were for a wonderful new ballpark book he and his friend Josh were writing and that he often used a microcassette recorder to take notes for his photo-log because it was so much easier than writing things down.

“I see,” the officer kept saying. “I see.” Then he said, “How about you let me hear some of these notes?” When the man said “notes,” he raised his hands and encompassed the imaginary words with quotation marks made of flesh and bone. All of this was greatly disturbing to Kevin, who observed to his left and right men and women clad in cowboy boots and dirty jeans, talking into cell phones as they slowly converged on him. But he played along and let the man have a listen. “Shot one—exterior façade on Texas Avenue … Shot two—exterior roof … Shot three—exterior train … Shot four—Irma’s Southwest Grill … Shot five—Biggio statue in Plaza.”

Apparently convinced that Kevin was no assassin, the guard looked him up and down one last time, then handed back the recorder. “Stay out of trouble,” he said, then walked away.

Baffled, Kevin resumed taking pictures. Then in the middle of the third inning, suddenly everything made sense when the ballpark announcer said, “Ladies and Gentlemen, we have two special guests in attendance tonight. Seated behind home plate are Chuck Yeager and former President George Bush.” Yeager and Bush stood, as did a reluctant Barbara who looked a bit miffed that her presence hadn’t been deemed worthy of acknowledgment over the P.A.

The many cowboy-hat-wearing Republicans in the crowd stood up and cheered, while the Democrats politely clapped. George and Chuck waved, and Barbara smiled. Soon everyone was standing regardless of party preference.

“And so, a new tradition is born,” Josh said, “the third-inning stretch.”

“What?” Kevin asked.

“This is just how the seventh-inning stretch started,” Josh said, and he went on to explain that the first US President to throw out a ceremonial first pitch at a baseball game was William Howard Taft on Opening Day in 1910. According to legend, before the season opener between the Washington Senators and Philadelphia Athletics at Griffith Stadium in D.C., on a whim umpire Bill Evans handed Taft the game ball and asked him to toss it to the plate. The president happily obliged and every chief executive since Taft except for Jimmy Carter has kicked off at least one season during his tenure by tossing out a first pitch in D.C. or Baltimore.

“But what does that have to do with the seventh inning?” Kevin asked, when Josh appeared finished with his story.

“Oh, yeah,” Josh said. “I nearly forgot my point.” He then explained how Taft, the most obese president ever, once stood up to stretch his legs in the middle of the seventh inning. Everyone else in the stadium rose to show respect to the chief executive, thinking the president was about to leave. A few minutes later Taft nonchalantly sat back down after cutting to the front of the concession line and getting a half-dozen hot dogs. Afterwards he was quoted as saying, “What, me leave a game early? Are you kidding? [Walter] Johnson had a shutout going.”

The next night, the Washington fans stood to stretch their legs in the seventh inning just as the president had, and soon the practice spread throughout baseball. People all across America were getting plumper and the ballpark seats weren’t getting any bigger, so the stretch came along just in time.

“Good story,” Kevin said when Josh had finished. “You know your baseball trivia. But here’s one for you. Where did Taft go to college?”

“I have no idea,” Josh said.

“Yale University,” Kevin replied. “Same as George H.W. Bush.”

TEXAS RANGERS,

TEXAS RANGERS,RANGERS BALLPARK IN ARLINGTON

A Texas-Sized Ballpark

A

RLINGTON

, T

EXAS

255 MILES TO HOUSTON

560 MILES TO KANSAS CITY

650 MILES TO ST. LOUIS

785 MILES TO DENVER

T

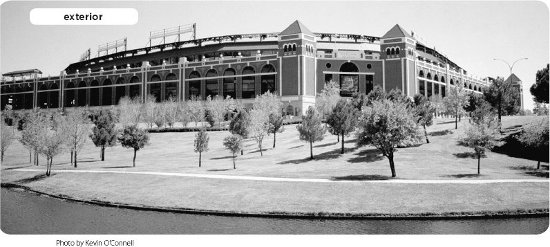

he saying “Everything is bigger in Texas,” could have been coined exclusively in reference to Rangers Ballpark in Arlington. If this is a ballpark, it’s the biggest one we’ve ever seen. But Texans have a reputation for being fiercely independent in their thinking and for doing things their own way. Rangers Ballpark is in reality a stadium masquerading as a ballpark, an impressive structure with an exterior facade that gives the impression of being a baseball fortress complete with turrets at its beveled corners. The walls do not attempt to mask the seating bowl or minimize it, but rather corral the structure, giving fans inside plenty of room to spare. There is no pretense of intimacy from the exterior, though within, Rangers Ballpark has more than its share of good seats, personality, and charm.

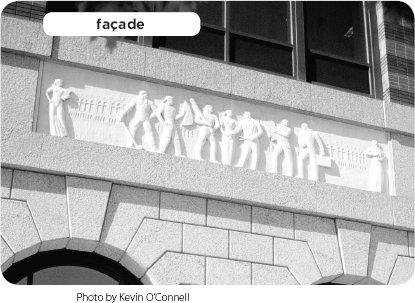

Rangers Ballpark is reminiscent of several stadiums built during the game’s classic era. A roof-topped, double-decked outfield porch in right field is quickly recognizable to fans of Tiger Stadium. The white steel filigree ringing the upper deck would please any fan of old Yankee Stadium. And the many irregularities of the outfield fence are clearly patterned after the nooks and crannies created by the old wall at Ebbets Field. As for the granite façade, it combines the red brick and retro turrets of Camden Yards with the arches of Comiskey Park. When Rangers Ballpark first opened, it had a manually operated out-of-town scoreboard built into the sixteen-and-a-half-foot-high left-field wall too. That edifice and its scoreboard were reminiscent, of course, of Fenway Park’s left-field Monster and slate board. The old-timey score-tracker was replaced by a modern electronic board in 2009, though. And then that board was updated to an ever better high-definition one in 2011. Who knows, perhaps by the time the next version of this book comes out fans in Arlington will be wearing 3-D goggles so as to best appreciate the latest scoreboard techno-upgrade.

Despite these nods to other yards, Rangers Ballpark projects a distinctly Texan flair. Lone Stars and longhorn steer-heads adorn the exterior walls and are visible throughout the ballpark inside. While many of the facilities built during the retro renaissance opened their outfields to allow for city skyline views, the Rangers enclosed the ballpark with a four-story office building in center that provides the ballpark with a signature look. Consisting primarily of glass, the building has a white steel multilevel facade, which provides porches for the offices and a unique backdrop for baseball. This white steel also traces the roofline of the ballpark, both inside and out, providing a nicely unified theme. The office building and the two-story-high billboards on its roof temper the strong Texas winds that would otherwise wreak havoc on fly balls. The playing surface is also sunk twenty-two feet below street level to minimize the effects of the wind.

In the shadows of the office building resides a grassy berm. Appearing between right and left-field bleachers, this sloped lawn serves as a unique center-field batter’s eye. It provides an ideal backdrop for hitting and is the frequent landing site of home run balls in this hitter-friendly park. Behind the berm and bleachers is a picnic area for fans to enjoy. And clearly fan enjoyment was paramount in the minds of the Rangers brass when they conceived their new digs. Residing next to a two-hundred-acre amusement park, Rangers Ballpark offers as complete a game-day experience as you’ll find in the American Southwest. As well as the restaurants and shopping facilities that have become standard fare in today’s parks, and concession stands that offer a wealth of options, there is plenty else to do and see inside on game day. Unfortunately, though, the expansive baseball museum that once resided in right field—the Legends of the Game Museum and Learning Center—has shuttered its doors and packed up.

Josh:

An usher told me they wanted to make more room for corporate events.

Kevin:

Why do you tell me things you know will upset me?

Rangers Ballpark resides adjacent to the Dallas Cowboys’ massive retractable-roof stadium amidst a more-attractive-than-usual sports complex that features well-manicured lawns, tree-lined trails along the shores of manmade ponds, a youth ballpark, and an outdoor amphitheater. With seats to accommodate more than eighty thousand football aficionados, Cowboy Stadium, or “The Jerry Jones Dome” as it is sometimes called, rates as the largest domed stadium in the world. It was built far enough from the baseball park, though, so as not to dwarf it too much.

The park rises from these environs beckoning fans to come inside where a lush green diamond awaits. “Sunset Red” granite mined at Marble Falls, Texas, is the most distinctive local material on display in the park’s structure. Meanwhile, decidedly Texan scenes that range from settling, to ranching, to space exploration, appear etched into white murals between the two levels of exterior arches. This classy sculpture work—which is called bas-relief, in case you were wondering—makes it well worth your tracing the perimeter of the stadium footprint outside for a look-see.

The funding for the ballpark came primarily from public sources, as the citizens of Arlington voted on January 19, 1991, for a one-half-cent sales tax increase to finance up to $135 million of the $191 million needed to complete the project. The remaining $56 million was provided by the Ranger ownership group, which included a Texan named George W. Bush. “Dubya” would go on to become governor of the Lone Star State and would eventually travel to Washington, D.C., to become president of the United States, retracing the path of the Rangers franchise, which in 1972 had made the reverse trip after starting out as the Washington Senators.

This is just one of many connections the Rangers share with the nation’s capital city. David M. Schwartz Architectural Services of Washington, D.C., was chosen to design the ballpark, while Dallas firm HKS, Inc., was the local architect of record.

Construction began in the spring of 1992 and took twenty-three months. When the facility opened in 1994 it was known officially as The Ballpark in Arlington. It kept that moniker for a decade before being rechristened as Ameriquest Field in Arlington courtesy of a naming-rights deal with Ameriquest Mortgage Company. It bore that corporate tag from May 2004 until March 2007 before being reintroduced, yet again, as Rangers Ballpark in Arlington. The Rangers lost the first game played in their yet-to-be-renamed new yard, an exhibition tilt against the Mets on April 1, 1994. Then they lost the regular-season opener ten days later against the then-American-League Brewers. Though their start was rough, the first season in the new park signified a time of great optimism for a team that had never before reached the postseason. Kenny Rogers highlighted the good fortune a new ballpark can bring to a franchise when he threw the first perfect game in Rangers’

history, a 4–0 blanking of the Angels at the Ballpark on July 28, 1994. With the gem, Rogers became the first left-hander in American League history to achieve perfection. He has since been joined on this short list of flawless Junior Circuit southpaws by David Wells (1998), Mark Buehrle (2009), and Dallas Braden (2010).

Speaking of history, Texas is one of two current American League teams that originated as the Washington Senators. The Minnesota Twins are the other. But the Rangers, perhaps, best exemplified the hapless Senator spirit. When the longtime Senators left Washington in 1960 to become the Minnesota Twins, the city was awarded an expansion franchise the very next year. And that expansion Senators team became the Rangers in 1972 when baseball struck out for a second time in the nation’s capital.

It’s hard to imagine that D.C. lost two baseball clubs in twelve years or that the members of the D.C. political establishment had such anemic pull they didn’t keep them in town. Maybe lawmakers, who hailed from home districts spread across the country and arrived in the Beltway with rooting interests already wed to teams back home, just didn’t care. But fans in the D.C. area cared. And in the final Senators game on September 30, 1971, with two outs in the bottom of the ninth, they made like Jimmy Stewart in

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington

and took a stand. Or rather, they created a stampede. They poured onto the field at RFK Stadium and refused to leave. Though the Senators were leading 7-5, the game had to be called and forfeited to the Yankees. That sort of eleventh-hour activism notwithstanding, fan support in D.C. really wasn’t sufficient to keep a franchise. The Senators drew just 824,000 fans in 1970 and only 655,000 in 1971. With that final home forfeit, the 1971 club finished 63-96, below .500 for the tenth time in the franchise’s eleven seasons.

Meanwhile Arlington was more than happy to open its doors to the American League’s perennial whipping horse. The Dallas/Fort Worth/Arlington Metroplex had been attempting to attract a Major League team for years with Arlington being the logical base to put the newcomers owing to its geographic location twelve miles east of Fort Worth and twenty miles west of Dallas. Two years after an attempt by Kansas City A’s owner Charlie O. Finley to move his team to Arlington failed, construction began on Turnpike Stadium in 1964. The ten-thousand-seat facility opened in 1965 and became the home of the minor league Dallas/Fort Worth Spurs of the Texas League. But Arlington would fall short of making the Show again in 1968 when the National League approved Montreal and San Diego as expansion sites.

Not long after, though, the push to bring baseball to Arlington gained new momentum when Robert E. Short, the Democratic National Committee treasurer, bought controlling interest in the Senators at the winter meetings in San Francisco in 1968. Turnpike Stadium was expanded to twenty thousand seats in 1970 and then in the latter half of the 1971 season Short received permission to move the Senators to Arlington for the beginning of 1972.

Turnpike Stadium was again expanded, this time to accommodate more than thirty-five thousand fans, and was renamed Arlington Stadium, because Arlingtonians felt Turnpike Stadium sounded too “bush league.” They were right. Then, after a long struggle to bring Major League Baseball to the area, local fans prepared for the arrival of big-league ball. And a player’s strike delayed the first game. Instead of starting in early April, the 1972 Rangers didn’t play their first home game until April 21 when they returned from a one-and-three road trip to beat the California Angels 7-6 in their first home game. They went on to post a four-game sweep of the Halos in a series that attracted a disappointing total of forty-two thousand fans. They went on to finish the year 54-100 and ranked tenth in the twelve-team AL in attendance, drawing just 662,000 fans to seventy-seven home dates. Neither the Rangers, their fans, nor their ballpark seemed ready for the big time quite yet.

Arlington Stadium had been reconstructed several times before its opening, and the resulting patchwork of misfit sections and bleachers shared more than a passing similarity to the woebegone Washington Senators’ old Griffith Stadium. Arlington also had the reputation for being

the hottest place to play in the Major Leagues, as temperatures rarely dipped below ninety degrees during the summer months. Making matters worse, the seats in Arlington were completely uncovered, so fans were exposed to the unforgiving Texas sunrays during day games. For this reason, most games were played at night, even on Sundays, and the Rangers were the first team to forego the use of flannel uniforms. Like they say, necessity is the mother of invention.