Uncle John's Bathroom Reader Plunges into Pennsylvania (24 page)

Read Uncle John's Bathroom Reader Plunges into Pennsylvania Online

Authors: Bathroom Readers' Institute

In the last two minutes, the Wildcats converted 11 of 14 free throws to keep the title just out of the Hoyas' reach. As a team, Villanova made 9 out of 10 second-half shots to finish with a shooting percentage of 79 percent for the game, a tournament record that stands to this day. When McClain dove after a loose ball in the closing seconds and held it tight to his chest with one fist in the air, the once-mighty Hoyas' season ticked away.

On the podium, Gary McLain held the trophy above his head and Ed Pinckney shouted, “Look at the scoreboard . . . Every-body said Georgetown would win. Everybody! But it's us!”

And what of the Hoyas? After a season spent tormenting opponents with their physical play, they watched the Wildcats receive their commemorative gold watches in the postgame ceremony.

Â

Â

In 1885, York doctor George Holtzapple used oxygen to treat a patient suffering from pneumonia and then published his findings. He wasn't the first doctor to administer an oxygen treatment, but he was the first to write about it so that others could follow the example.

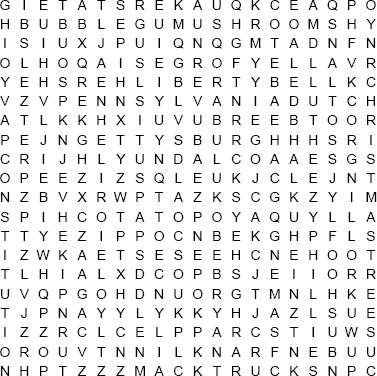

The words below all have a special association with Pennsylvania. See how many you can find. (Answer on

page 304

.)

ALCOA

AMISH

BEN FRANKLIN

BUBBLE GUM

CHEESESTEAK

CHRISTMAS TREES

COAL

CONSTITUTION

EAGLES

GETTYSBURG

GROUNDHOG

HEINZ

HERSHEY

HEX SIGNS

KEYSTONE STATE

KOBE BRYANT

LIBERTY BELL

MACK TRUCKS

MUSHROOMS

PENNSYLVANIA DUTCH

PHILLIES

PINK

POTATO CHIPS

PRETZELS

QUAKER STATE

ROCKY

ROLLING ROCK

ROOT BEER

SAUSAGE

SCRAPPLE

SHOOFLY

SLINKY

TURNPIKE

VALLEY FORGE

ZIPPO

ZOO

The piece of paper that started it all was written, approved, and even printed in Philadelphia

.

L

ife in Philadelphia in 1776 was chaotic. The Revolutionary War had begun the year before, but even in 1776, many people still hoped for reconciliation with England. By May, though, rebels who wanted a complete break from King George had ousted the loyalists and moderates from Pennsylvania's government. Not everyone agreed, but most of the other colonies had followed suit. When delegates from each state gathered at the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, their collective goal had turned from reconciliation to complete independence from England.

Many of the delegatesâmen like John Adams and Thomas Jeffersonâhad read Thomas Paine's pamphlet

Common Sense

(

see

page 38

), which presented a strong case for independence. Adams urged the Continental Congress to draw up a formal declaration of independence. The purpose: to make their goals known, let the English government (and the colonists) know what their grievances were, and explain why the colonies needed to be their own nation.

On June 10, the Continental Congress appointed five menâ

John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Roger Sherman, and Robert Livingstonâto draft the Declaration of Independence. Adams and Jefferson were expected to write the document; Franklin, who was 71 years old and in poor health, lent respectability to the committee; and Sherman was a respected New England politician who supported Adams. Only Livingston seemed an odd choice. He represented New York, a colony still against independence, but he might have been included to appease the colonists who feared a break with England.

Ultimately, the committee chose Jefferson to do the actual writing, though others could have done the job. John Adams was qualified, but most people thought his writing was dull. Even Adams himself told Jefferson, “You can write ten times better than I can.” As for Franklin, a proven author, many were concerned that if the wry and witty Franklin wrote the declaration, he'd hide a joke in it.

In the end, Jefferson was chosen because he was an eloquent author and had already put his thoughts about the colonies' rights on paper. Before the meeting in Philadelphia, Jefferson had drafted an article called “A Summary View of the Rights of British America,” which laid out his ideas about self-governance and offered justification for the Revolution. The article had made its way to Philadelphia ahead of him, and the other delegates had read and admired it.

From the day the committee formed to the day Jefferson finished the declaration's first draft took just 17 days. Jefferson wrote mostly in the suite of rooms he'd rented in a Philadelphia home. No diaries or minutes exist to describe his composition

process, but scholars are certain that Jefferson drew many of his ideas from a constitution he'd written for Virginia, listing his grievances against the king of England. He also borrowed from John Locke's

Second Treatise on Government

, which theorized that the people had rights and should rebel if their government didn't uphold them. Finally, he took ideas from other writers of the Enlightenment Era, who proposed that freedom and equality were mankind's inherent entitlements.

Jefferson gave Franklin and Adams a rough version on June 28, and they made some editorial suggestions. (When describing King George's attitude toward the colonies, for example, Franklin changed Jefferson's phrase “arbitrary power” to the more severe “absolute despotism.”) Jefferson incorporated their changes into a new copy and presented it to the Continental Congress on July 2.

For the most part, the delegates made few changes to the Declaration of Independence. They condensed some long paragraphs (like the one explaining why the king was a tyrant) into one or two sentences. But one passage led to debate: Jefferson's original version condemned the slave trade. Even though he owned slaves himself, Jefferson blamed England and King George for the practice, which he called a “cruel war against human nature.” But many of the colonies were slaveholding states, and other free states were sympathetic to the practice. The delegates refused to allow the condemnation of the slave trade to stand. Led by Georgia and South Carolina, a group of attendees voted out the paragraph.

Even with that argument settled, a unanimous vote eluded the Congress because New York refused to approve the declaration.

New York was still divided on the issue of independence, so the New York delegates abstained from the vote on July 4. All the other colonies voted in favor, though, and the declaration passed. The United States had asserted itself as a separate, independent country.

That same day, the Continental Congress sent the document to a printer so that copies could be rushed to all of the colonies and to General George Washington on the battlefield. On July 8, Colonel John Nixon of the Pennsylvania militia read the declaration to a crowd gathered in front of the State House in Philadelphia.

On July 19, Congress ordered an engrossed copy of the Declaration of Independence. Engrossed documents were written on parchment in a very large script, so they could be posted and read easily, and partly so they could be preserved for the ages. On August 2, John Hancock, the secretary of the Continental Congress, signed the engrossed copy with a grand flourishâfollowed by most of the other delegates. Even the New Yorkers who had been absent from the vote put their names to it. That engrossed, signed copy is now kept in the National Archives in Washington, D.C.

To read about the U.S. Constitution, turn to

page 258

.

Â

We always knew Pennsylvanians loved their pretzels. Now we know why

.

According to legend, a hobo approached Lititz, Pennsylvania, baker Julius Sturgis in 1850 looking for work and something to eat. Sturgis didn't have a job to offer, but he did invite the man to dinner with his family. After the meal, the hobo gave the baker a pretzel recipe as a thank-you. Sturgis had never baked pretzels before, but he tried out the recipe on his family, who liked them so much that the baker started selling the new snack around town.

By 1861, Sturgis's pretzels were so popular that he stopped selling bread altogether and opened the Sturgis Pretzel Houseâthe first commercial pretzel bakery in the United States. In 1936, the Sturgis family opened another pretzel bakeryâthe Tom Sturgis Pretzel Bakery in nearby Reading. Both are still around today, and both are still operated by the Sturgis family.

â¢

The first documented evidence of pretzel-making dates to the 12th century in what is now southern Germany. Back then, the snack was baked in long sticks and was known as a

brezl

, a term that most etymologists believe derives from the Latin

bracchium

, meaning “arm.”

â¢

It makes sense that Pennsylvaniaâparticularly the southeast of the stateâwould be the place that pretzel-making first flourished in the United States. That's where thousands of immigrants from southern Germany settled starting in the 1700s.

Along with many other traditions, they brought their pretzel-making recipes with them.

â¢

Pennsylvania is famous for both the soft pretzels that came to the New World with German immigrants and the hard pretzels that developed later. However, the soft varietyâtwisted, chewy, and often served warm with mustardâare what the state is especially famous for.

â¢

How popular are pretzels in Pennsylvania? The average American consumes about two pounds of pretzels a year; in Philadelphia, it's about 24 pounds a year.

â¢

In 1983, Representative Robert Walker of Pennsylvania stood in Congress and extolled the virtues of pretzels. He announced that from then on (unofficially), April 26 would be known as “National Pretzel Day.” It is still celebrated by pretzel enthusiasts all over the country, especially in Pennsylvania.

â¢

In case you're reading this in Beijing, China, and hankering for a Pennsylvania pretzel, Lancaster-based pretzel maker Auntie Anne's opened a store in Beijing in 2008. It's just one of 940 stores the chain operates worldwide.

â¢

In 2003, Shuey's Pretzels, near the town of Cleona in Lebanon County, made a two-foot-wide, ten-pound pretzel. It was dropped from the tower of Cleona's fire station at midnight on New Year's Day, mimicking the ball drop in New York's Times Square.

â¢

On January 13, 2002, President George W. Bush fainted, fell, and bruised his face while watching a football game in the White Houseâafter choking on a pretzel. (White House officials would not confirm what kind of pretzel it wasâor if it was made in Pennsylvania.)