Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition (30 page)

Read Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition Online

Authors: Colin Barrow,John A. Tracy

Tags: #Finance, #Business

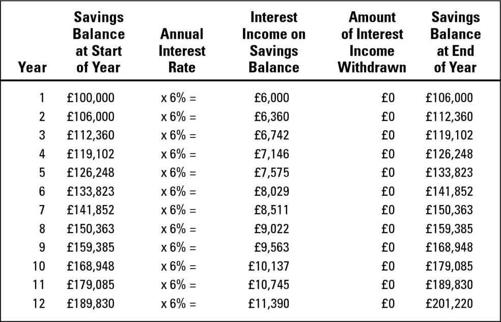

Figure 4-2 illustrates how your savings balance would grow year by year, assuming a 6 per cent annual interest rate for all 12 years. This growth comes at a price - you can't take out annual earnings. Not withdrawing annual earnings is called

compounding

; the term

compound interest

refers to not withdrawing interest income. Compounding means that you save more and more each year. To emphasise this important point, notice in Figure 4-2 that we include a column for the amount of interest income withdrawn each year (which is zero every year in this example).

Furthermore, the entire interest income each year is subject to individual income tax - unless the money is invested in a tax-efficient pension fund. For instance, in year 4 your interest income is £7,146 (see Figure 4-2). At the higher 40 per cent tax rate you would owe £2,858 income tax on your interest income.

The rule of 72

A handy trick of the trade is called the rule of 72. In Figure 4-2, at the end of the 12th year, notice that your savings balance is about £200,000 (rounded off) - exactly twice what you started with. This is a good example of the rule of 72. The rule states that if you take the periodic earnings rate as a whole number and divide it into 72, the answer is the number of periods it takes to double what you started with. Sure enough: 72 ÷ 6 = 12. Doubling your money at 6 per cent per year takes 12 years.

The rule of 72 assumes compounding of earnings. It's amazingly accurate over a broad range of earnings rates and number of periods. For example, how long does it take to double your money at an 8 per cent annual earnings rate? It takes nine years (72 ÷ 8 = 9). If you earn 18 per cent per year, you double your money in just four years.

One caution: For very low and very high earnings rates, the rule is not accurate and should not be used.

Unfortunately, compounding of earnings is often touted as a sort of magical way to build wealth over time or to make your money double. Don't be suckered by this claim. You sacrifice 12 years of earnings to make your money grow; you don't get to spend the interest income on your savings for 12 years. We don't call this magic, we call it

frugal

. Compounding is not magical - it's a conservative way to build wealth that requires you to forgo a lot of spending along the way.

Figure 4-2:

Growth in savings balance assuming no withdrawals and full compound-ing of annual interest income.

Individuals as investors

The last two decades have seen a remarkable explosion in the number of individuals who invest in the stock market - either directly by buying and selling stocks and shares or indirectly by putting their money in shares of mutual funds (open-end investment companies that act as intermediaries for individuals). Also during this time span, a sea change has occurred in the arena of retirement pension planning, mainly a fundamental shift away from traditional

defined-benefit

pension plans (which are based on years of service to an employer and salaries during the final years of employment) to

defined-contribution

plans (which are based on how much money has been put into individual retirement investment accounts and the earnings performance of the investments).

National Insurance is the government-sponsored defined-benefit retirement plan. Your monthly retirement benefit depends on how many years you have worked and paid the required amount of National Insurance. In the private sector, a large percentage of retired employees still depend on traditional defined-benefit pension plans. However, the growth of defined-contribution plans has been phenomenal - although we think most individuals don't realise that this type of retirement plan puts much more of a burden on them to understand investment performance accounting.

The twofold nature of return on investment

Putting money into savings, such as a savings account or a government bond, is low risk. In contrast, putting money into an

investment

, such as company shares and bonds or property, means that you are taking on more risk - that you may lose part of the amount of money you invest and that the earnings from your investment may fluctuate from year to year. There's no such thing as a free lunch. If you want the higher earnings, you must take greater risk.

Earnings from

investing

capital are generally not referred to as earnings on investment, but rather as

return on investment

(ROI). ROI consists of two parts: (1)

cash income

(if in fact there is cash income) and (2)

market value appreciation

or depreciation

. When you invest, you put your money in stocks and bonds (which are called

securities

), or mutual funds, or property, or whatever. The range of possible investments is diverse, to say the least. We recommend Tony Levene's

Investing For Dummies

(John Wiley & Sons, Ltd).

He explains the wide range of investments open to individuals, from mutual funds to property and most things in between. Investors should understand how return on investment is accounted for no matter which type of investment they choose.