Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition (31 page)

Read Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition Online

Authors: Colin Barrow,John A. Tracy

Tags: #Finance, #Business

The return on investment, or ROI, for a period is computed as follows, and is usually expressed as a percentage:

Return for Period ÷ Amount Invested at Start of Period = Rate of Return on Investment (ROI)

Suppose, for example, that your £100,000 investment at the start of the year provided £2,500 cash flow income during the year, and the market value of your investment asset increased £7,500 during the year. Your total return is £10,000 for the year, and your ROI is 10 per cent for the year: £10,000 return ÷ £100,000 invested = 10 per cent ROI.

Often, people use the term

ROI

when they really mean

rate

, or

percentage

,

of ROI. Like some words that have a silent character, ROI is frequently used without rate or percentage. Anytime you see the % symbol, you know that the

rate

of ROI is meant. In any case, the ROI rate is not a totally satisfactory measure. For instance, suppose you tell us that your investments earned 18 per cent ROI last year. We know your wealth, or capital, increased 18 per cent - although we don't know how much of this return you received in cash income and how much was an increase in the market value of your investment, and we don't know whether you spent your cash income or reinvested it.

Individuals, financial institutions, and businesses always account for the cash income component of investment return. However, the market value gain or loss during the period may or may not be recorded. Most individuals who invest in property, stocks, bonds, and so on, do not record the gain or loss in the market value of their investments during the period. So they do not have a full and complete accounting of ROI for the period.

The investment accounting that most individuals do is governed largely by what's required for income tax purposes. Unrealised market value gains are not taxed, so most investors do not record market value gains. Nevertheless, they keep an eye on market value ups and downs, in addition to their cash income. For example, property investors generally do not measure and record market value changes each year, although they keep an eye on the prices of comparable properties.

In contrast, financial institutions, including banks, mutual funds, insurance companies, and pension funds, are governed by generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). They invest in marketable securities that are held for sale or trading or that are available for sale. GAAP requires that changes in market value of these investments be recognised. On the other hand, GAAP does not require the recording of market value gains and losses for their investments in fixed-income debt securities (for example, bonds and notes) that are held until maturity.

The main point of this discussion is that you should be very clear about what's included and not included in ROI. As just discussed, many individuals do not capture market value changes during the year in accounting for the return, or earnings on their investments - they account for only the cash income part, which gives an incomplete measure of ROI. On the other hand, when a mutual fund advertises that its annual ROI was 18 per cent last year you can be sure that it

does

include the market value gains in this rate (as well as cash income, of course).

A real-world example of ROI accounting

Suppose you invest £94,757.86 today in a UK Gilt (Government borrowing instrument) that has three years to go until its maturity date. The face, or par, value of this debt security is £100,000, which is its maturity value three years hence and which is also the basis on which interest is computed. This gilt-edged stock pays 6 per cent annual interest, which is paid twice a year. The 6 per cent rate is sometimes called the

coupon rate

because in the good old days (before direct deposit by electronic funds transfer), investors in debt securities had to clip one of the interest coupons attached to the debt certificate as it came due and mail the coupon for payment of the interest.

Every six months, the UK Treasury Department sends you £3,000 (depositing the amount directly in your bank account). Assume that you spend the £3,000 twice-yearly interest income. So far, so good. But now comes a tough question: What's your ROI rate on this investment?

By paying £94,757.86, you buy the Gilt at a

discount

from its £100,000 maturity value. The discount provides part of your return on investment in addition to your cash-flow interest income. Most of your ROI consists of cash income every six months. But part consists of

market value appreciation

as the note moves closer to its maturity date. This second component does not provide cash flow until the maturity date is reached. Taking both parts into account, your ROI rate is more than the 6 per cent annual interest rate based on the par value of the note.

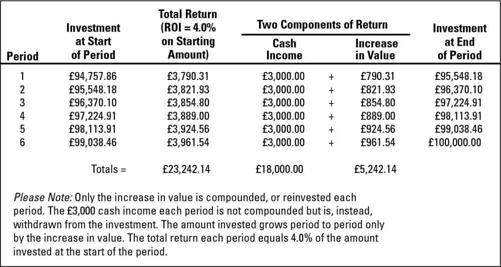

Tell you what. Guess that the correct ROI rate is 4 per cent per period (every six months), and see whether this rate is correct. We'll walk you quickly through the accounting in this example to test out the 4 per cent ROI rate. Figure 4-3 demonstrates that in each period, the return on the investment indeed equals 4 per cent of the amount invested at the start of the period. The investor receives only £3,000 per period of cash income. The increase in the value of the note each period as it moves toward its maturity value provides the remainder of the return each period. The total increase in value over the three years is not received until the maturity date, at which time the investment is cashed out. At this time, the individual has to find another investment to put his or her £100,000 into.

An important note regarding annualised ROI rates

In the investment example in Figure 4-3, the increase in value each period is not received in cash. Therefore, it is ‘automatically' reinvested, or compounded. Due to this compounding, the amount invested increases period to period - see the left column. As a result, the increase in the value amount is larger from period to period.

Figure 4-3:

Investing in a UK Gilt at a discount from its maturity value to illustrate a higher ROI rate than just the periodic interest rate paid on the investment.

Seems odd, doesn't it? A 4 per cent ROI earned each half-year is treated as equivalent to 8.16 per cent ROI earned for the whole year. The purpose is to put all investments on the same footing, as it were - so that annual ROI rates can be compared among different investments. The standard practice in the world of finance is to express ROI rates on the basis of a one-year period - even though the investment may be for a shorter period of time. When a less-than-one-year ROI rate (or interest rate) is converted into an equivalent full-year rate, the shorter-term rate is

annualised.

Usually the word

annualised

is not included; it is assumed that you understand that shorter-term rates have been converted into an equivalent annual rate. Any investment income received during the year is assumed to be compounded (reinvested) for the rest of the year to determine the annualised ROI rate, or we should say just the ROI rate.