Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition (54 page)

Read Understanding Business Accounting For Dummies, 2nd Edition Online

Authors: Colin Barrow,John A. Tracy

Tags: #Finance, #Business

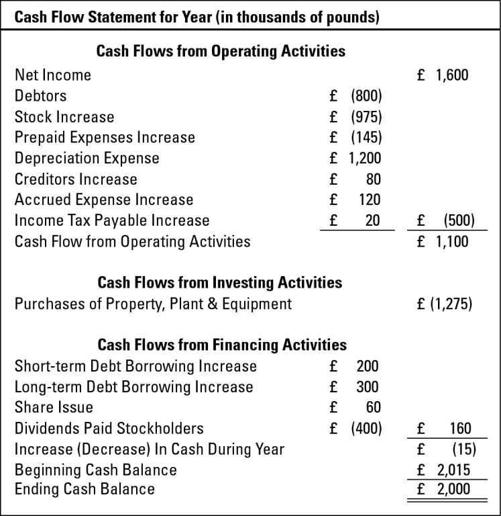

What do the figures in the first section of the cash flow statement (see Figure 7-2) reveal about this business over the past period? Recall that the business experienced rapid sales growth over the last period. However, the downside of sales growth is that operating assets and liabilities also grow - the business needs more stock at the higher sales level and also has higher debtors.

Figure 7-2:

Cash flow statement for the business in the example.

The business's prepaid expenses and liabilities also increased, although not nearly as much as debtors and stock. The rapid growth of the business yielded higher profit but also caused quite a surge in its operating assets and liabilities - the result being that cash flow from profit is only £1.1 million compared with £1.6 million in net income - a £500,000 shortfall. Still, the business had £1.1 million at its disposal after allowing for the increases in assets and liabilities. What did the business do with this £1.1 million of available cash? You have to look to the remainder of the cash flow statement to answer this key question.

A very quick read through the rest of the cash flow statement (refer to Figure 7-2) goes something like this: The company used £1,275,000 to buy new fixed assets, borrowed £500,000, and distributed £400,000 of the profit to its owners. The bottom line (should we use that term here?) is that cash decreased £15,000 during the year. Shouldn't the business have increased its cash balance, given its fairly rapid growth during the period? That's a good question! Higher levels of sales generally require higher levels of operating cash balances. However, you can see in its balance sheet at the end of the year (refer back to Figure 6-2) that the company has £2 million in cash, which, compared with its £25 million annual sales revenue, is probably enough.

Where to put depreciation?

Where the depreciation line goes within the first section (operating activities) of the cash flow statement is a matter of personal preference - no standard location is required. Many businesses report it in the middle or toward the bottom of the changes in assets and liabilities - perhaps to avoid giving people the idea that cash flow from profit simply requires adding back depreciation to net income.

A better alternative for reporting cash flow from profit?

We call your attention, again, to the first section of the cash flow statement in Figure 7-2. You start with net income for the period. Next, changes in assets and liabilities are deducted or added to net income to arrive at cash flow from operating activities (the cash flow from profit) for the year. This format is called the

indirect method.

The alternative format for this section of the cash flow statement is called the

direct method

and is presented like this (using the same business example, with pound amounts in millions):

Cash inflow from sales £24.2

Less cash outflow for expenses

23.1

Cash flow from operating activities £1.1

You may remember from the earlier discussion that sales revenue for the year is £25 million, but that the company's debtors increased £800,000 during the year, so cash flow from sales is £24.2 million. Likewise, the expenses for the year can be put on a cash flow basis. But we ‘cheated' here - we have already determined that cash flow from profit is £1.1 million for the year, so we plugged the figure for cash outflow for expenses. We would take more time to explain the direct approach, except for one major reason.

Although the Accounting Standards Board (ASB) expresses a definite preference for the direct method, this august rule-making body does permit the indirect method to be used in external financial reports - and, in fact, the overwhelming majority of businesses use the indirect method. Unless you're an accountant, we don't think you need to know much more about the direct method.

Sailing through the Rest of the Cash Flow Statement

After you get past the first section, the rest of the cash flow statement is a breeze. The last two sections of the statement explain what the business did with its cash and where cash that didn't come from profit came from.

Investing activities

The second section of the cash flow statement reports the investment actions that a business's managers took during the year. Investments are like tea leaves, which serve as indicators regarding what the future may hold for the company. Major new investments are the sure signs of expanding or modernising the production and distribution facilities and capacity of the business. Major disposals of long-term assets and the shedding of a major part of the business could be good news or bad news for the business, depending on many factors. Different investors may interpret this information differently, but all would agree that the information in this section of the cash flow statement is very important.

Certain long-lived operating assets are required for doing business - for example, Federal Express wouldn't be terribly successful if it didn't have aeroplanes and vans for delivering packages and computers for tracking deliveries. When those assets wear out, the business needs to replace them. Also, to remain competitive, a business may need to upgrade its equipment to take advantage of the latest technology or provide for growth. These investments in long-lived, tangible, productive assets, which we call

fixed assets

in this book, are critical to the future of the business and are called

capital expenditures

to stress that capital is being invested for the long haul.

One of the first claims on cash flow from profit is capital expenditure. Notice in Figure 7-2 that the business spent £1,275,000 for new fixed assets, which are referred to as

property, plant, and equipment

in the cash flow statement (to keep the terminology consistent with account titles used in the balance sheet, because the term

fixed assets

is rather informal).

Cash flow statements generally don't go into much detail regarding exactly what specific types of fixed assets a business purchased - how many additional square feet of space the business acquired, how many new drill presses it bought, and so on. (Some businesses do leave a clearer trail of their investments, though. For example, airlines describe how many new aircraft of each kind were purchased to replace old equipment or expand their fleets.)