When the War Was Over (60 page)

Read When the War Was Over Online

Authors: Elizabeth Becker

A Khmer Rouge official weaving cloth in a cooperative (December 1978).

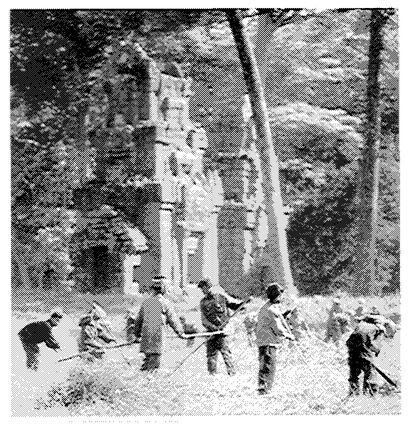

Clearing a field (December 1978).

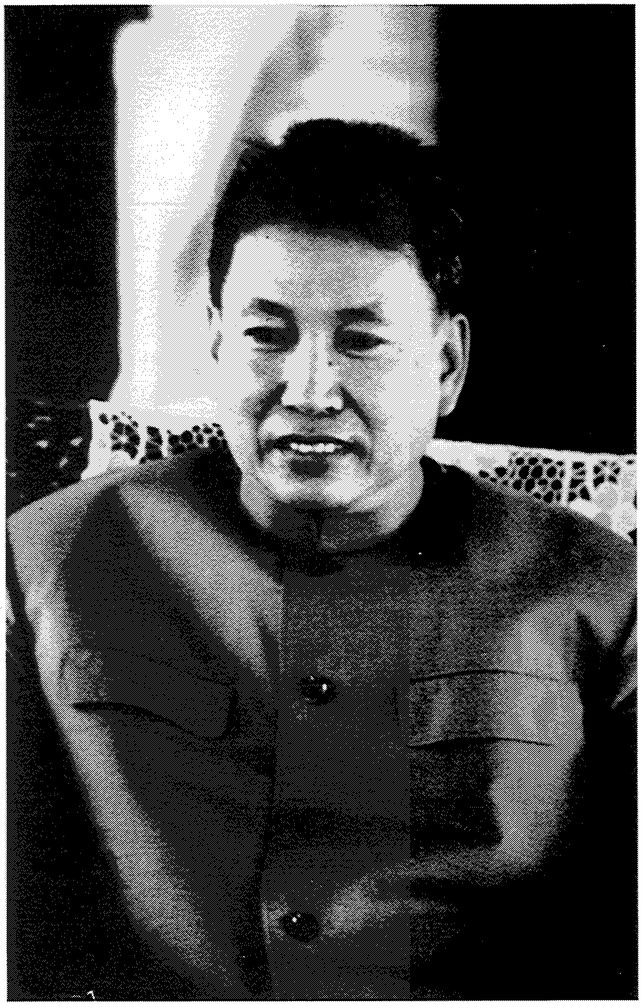

Pol Pot photographed by the author in December 1978.

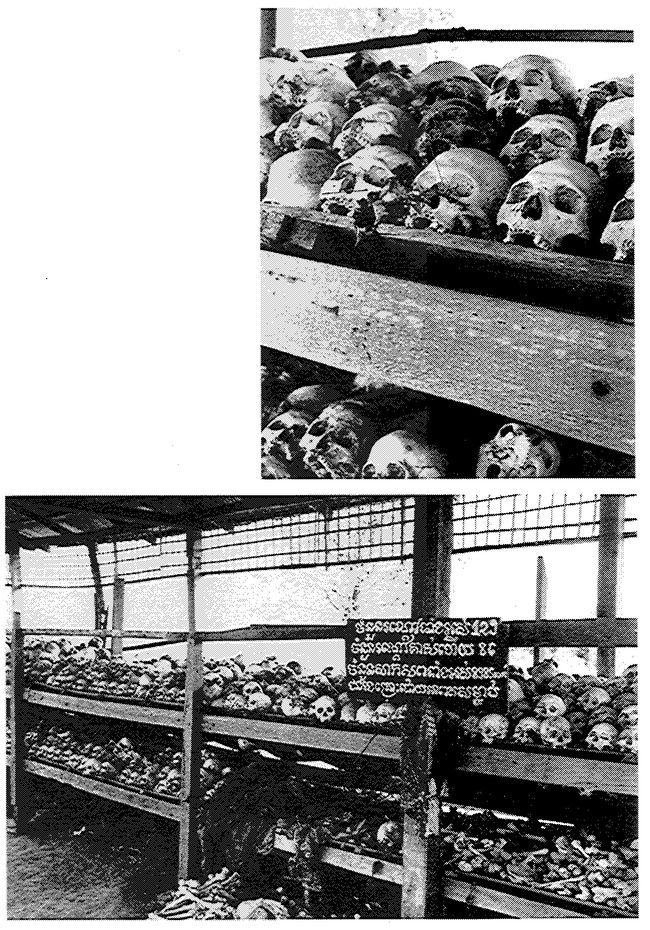

The first memorial to the victims of the Khmer Rouge genocide was a simple, covered open-air shed with shelves for the skulls and bones dug up from mass graves outside Phnom Penh.

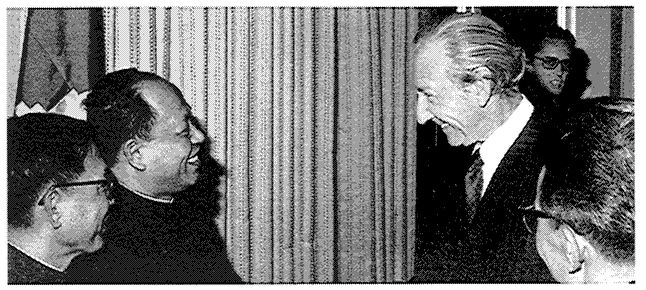

U.N. Secretary General Kurt Waldheim and Ieng Sary, Foreign Minister of Democratic Kampuchea. Throughout the 1980s, Khmer Rouge diplomats represented Cambodia at organizations.

U.S. General John Vessey (left) greeting Vietnamese Foreign Minister Nguyen Co Thach in Hanoi for a meeting on U.S.-Vietnamese relations.

The first meeting of Prince Norodom Sihanouk (on the left) and Prime Minister Hun Sen at Fere-en-Tardenois, France, in December 1987.

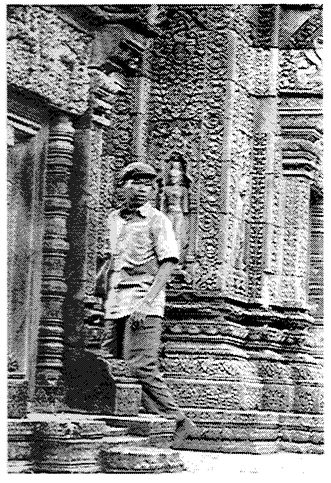

A Khmer Rouge guard at a temple in Angkor Wat (December 1978).

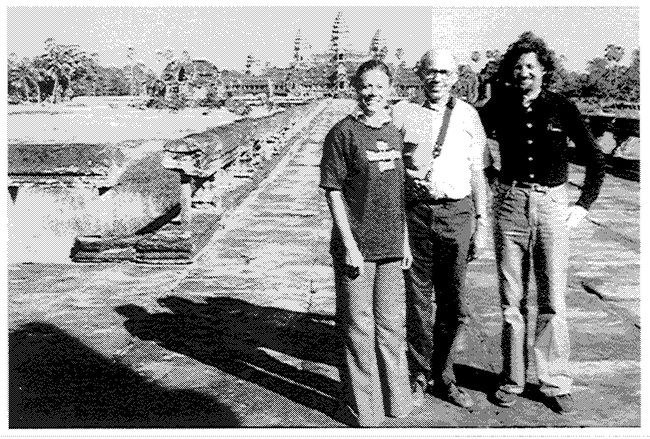

A group photo in front of the spire at Angkor Wat. From left: Elizabeth Becker, Richard Dudman, and Malcolm Caldwell (December 1978).

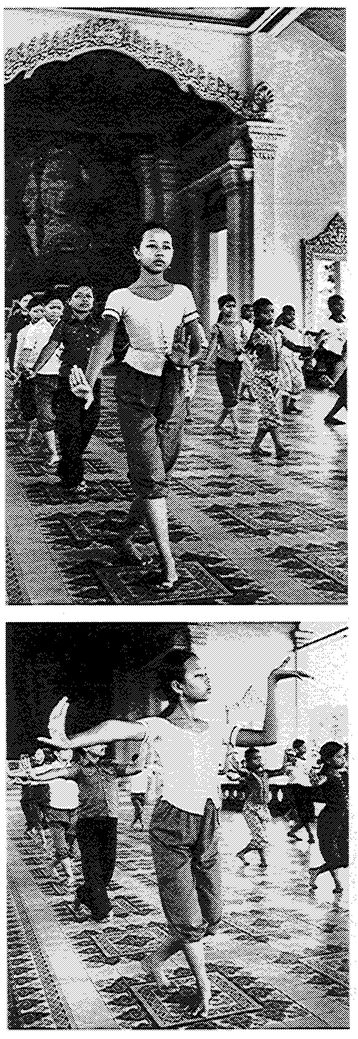

Dancers practice for the Cambodian ballet at the royal palace in 1982. The ballet troupe was one of the first cultural groups revived by the Vietnamese after overthrowing the Pol Pot regime.

On July 17, the Zone cadre gathered for a midyear review and issued a report, which touched on border matters and military problems. One copy of that report survives, a report sent to Comrade Rin, who headed the Eastern Zone's Fourth Division. His full name is Heng Samrin, a man who would also proclaim his opposition to Pol Pot in 1978. The conference presumably was headed by So Phim. The report contains guidelines for the commanders of the Eastern Zone troops. It was a secret document, not meant for distribution beyond the “command level.”

It reads in part:

Our second guideline in the military sphere is that we must continue to be on guard and be prepared to do battle with and smash the enemy at all times, day or night; we absolutely must not allow the enemy to enter into and commit aggression against any part of our territory. If the enemy commits aggression against us, we must respond by stopping him and smashing him and we will not limit ourselves to stopping him and smashing him on our land, we must cross into and stop and smash him right on his land. This is intended to further increase his difficulties. If things are done in this manner, the enemy's fear of us will be increased and, eventually, he will no longer dare to repeat his aggression against us; rather, it will be his turn to strain to stop us.

The report cautions that this is a “guideline” and not an immediate order. “Only when the time comes that we must do battle will we bring up this guideline. . . . No locality or unit is permitted to do battle separately; rather, there must be general unity.”

The issuance of the report coincided with the announcement that Laos and Vietnam had agreed to sign a special treaty of friendship. Phnom Penh had adamantly refused to be a partner to such a treaty with Vietnam. The Cambodians saw the Lao treaty as a turning point for their own fortunes. “If Laos had not joined the Indochinese Federation, then the Vietnamese could

not have set it up,” Ieng Sary said. “But the Lao cadre were already grasped by the Vietnamese at all levels.”

not have set it up,” Ieng Sary said. “But the Lao cadre were already grasped by the Vietnamese at all levels.”

This was the interpretation of special treaties with Vietnamâthat they were the foundation of a resurrected Indochinese Federation that Hanoi would dominate and which would spell the end of Cambodian independence. In July, Pol Pot and the party began to worry that the Vietnamese could win the border war. The party center took a closer look at the troops defending Cambodia's vulnerable Eastern Zone border. Pol Pot and Duch reportedly sent So Phim a new list of Eastern Zone traitors. But Phim chose to dispute this new order of execution. He protested that the men cited could not be traitors, they were his trusted lieutenants. There must be a mistake.

The mistake was Phim's in Duch's opinion. By refusing to accept Duch's list of traitors, Phim had implicated himself.

In August the border quieted down. Vietnam Defense Minister Vo Nguyen Giap toured his troops. There were rumors of a cease-fire.

The “second guideline” became the order of the day. Eastern Zone troops attacked the Vietnamese inside Tay Ninh province. The Eastern Zone troops, including those of Heng Samrin's Division 4, went deep into Vietnamese territory supposedly both to probe Vietnamese defense capabilities and to warn Vietnam against pursuing its border claims. But in fact they mostly massacred Vietnamese civilians. Vietnam was not deterred but provoked. With the help of information gleaned from interrogating Hun Sen, the Vietnamese began planning a major counterattack.

COMING OUTOn September 27, 1977, Pol Pot addressed the nation and declared himself the previously unknown leader of the country and the Communist Party of Kampuchea. The mystery was over.

Pol Pot's speech was five hours long. He told the people that “Angka” was the communist party, that this party had been the hidden force behind the scenes throughout Cambodia's modern history. He gave the party credit for pushing Sihanouk into his neutralist, nonaligned position in the fifties and sixties. He said the party had maneuvered Sihanouk to work for the communists after Lon Nol's coup in 1970 solely as a “tactical alliance.”

Other books

The Devil You Know by Marie Castle

Ambrosia (Nectar Trilogy, Book 2) by Prince, DD

Green Algae and Bubble Gum Wars by Annie Bryant

Slow Burn by Christie, Nicole

Playboy Doctor by Kimberly Llewellyn

A Fireproof Home for the Bride by Amy Scheibe

Ashleigh's Dilemma by Reid, J. D.

Manage Me (Toven's Circus #1) by Marlowe Fox