Which Way to the Wild West? (13 page)

Read Which Way to the Wild West? Online

Authors: Steve Sheinkin

S

o now, with fights raging all over the Plains, the Union Pacific was about to cut into Plains Indians' land. Well, at least the UP had solved its labor problem. When the Civil War ended in April 1865, thousands of army veterans headed west in search of work on the railroads. So did lots of Irish immigrants and former slaves.

o now, with fights raging all over the Plains, the Union Pacific was about to cut into Plains Indians' land. Well, at least the UP had solved its labor problem. When the Civil War ended in April 1865, thousands of army veterans headed west in search of work on the railroads. So did lots of Irish immigrants and former slaves.

With 10,000 workers, the UP started building more than a mile of track a day across the Great Plains. Crews of “iron men” laid down the seven-hundred-pound iron rails, then teams of “spikers” came up behind them to hammer in spikes holding the rails in place. Rolling along at the end of the track was a long supply trainâreally more like a town on wheels. There were train cars with warehouses, blacksmith shops, butchers, and kitchens, and several with bunk beds. (A teenage worker named Erastus Lockwood said the bunks were covered with fleas, so he and his friends preferred to sleep on the roof of the train.)

By October 1866 the UP tracks reached nearly 250 miles west of Omaha. Thomas Durant decided this called for a big party, and he invited politicians and investors to come celebrate the progress. Bands and magicians entertained the guests, while chefs prepared a menu of western specialties (such as “buffalo tongue” and “braized bear in port wine”). Then everyone went to sleep in fancy tents with mattresses.

Durant's guests were having a great timeâuntil the next morning. It was then, according to the UP engineer Silas Seymour, that the partygoers were “startled from their slumbers by the most unearthly whoops and yells of the Indians.” People stuck their heads out of their tents and were terrified to see Indians running through camp, shouting and waving tomahawks.

They were relieved to realize that this was all part of the party. These were Pawnees, allies of the Americans. Durant had paid them to put on this little show. He wanted his guests to feel like they had experienced the real live Wild West.

The tourists went home happy, and the Union Pacific continued building across the Great Plains. But as the workers moved farther west, they started laying tracks into the territory of powerful Plains Indians nations such as the Lakota, the Cheyenne, and the Arapaho. These groups were in no mood to join a celebration for a railroad through their land.

A

lready alarmed by white settlers, gold seekers, and wagon roads, the Plains Indians saw the advancing railroad as the biggest threat yet to their way of life. They watched hunters hired by the Union Pacific shoot thousands of buffalo to feed railroad workers. And they knew the railroad would bring more soldiers and settlers to the Plains.

lready alarmed by white settlers, gold seekers, and wagon roads, the Plains Indians saw the advancing railroad as the biggest threat yet to their way of life. They watched hunters hired by the Union Pacific shoot thousands of buffalo to feed railroad workers. And they knew the railroad would bring more soldiers and settlers to the Plains.

In August 1867, near Plum Creek in Nebraska, a Cheyenne named Porcupine was riding with a group of warriors when they saw a train for the first time. “We looked at it from a high ridge,” he remembered. “Far off it was very small, but it kept coming and growing larger all the time, puffing out smoke and steam.”

After the train passed, the men rode down to the tracks to take a closer look. “We talked of our troubles,” Porcupine said. “We were feeling angry and said among ourselves that we ought to do something.”

The warriors yanked down the telegraph wire that ran along the train track. They used it to tie a few heavy pieces of wood across the tracks. Then they sat by the tracks and waited. Soon after dark they heard a rumbling sound. It was getting louder.

“It's coming,” Porcupine said.

What was wrong with the telegraph line along the Union Pacific track? William Thompson got the job of finding out. “About nine o'clock Tuesday night,” he said, “myself and five others left Plum Creek station, and started up the track on a hand car, to find the place where the break in the telegraph was.” The men saw that something was blocking the tracks, but too lateâthe handcar slammed into a pile of wood and flew off the tracks, tossing Thompson and the ot men into the air.

A

s William Thompson and the other repairmen hit the ground, Porcupine and his fellow warriors jumped up with their weapons.

s William Thompson and the other repairmen hit the ground, Porcupine and his fellow warriors jumped up with their weapons.

“We fired two or three shots,” Thompson said, “and then, as the Indians pressed on us, we ran away.”

Thompson hadn't gotten far when he felt a bullet rip through his right arm. He kept running. A Cheyenne warrior chased him down and clubbed him with a rifle. “He then took out his knife,” Thompson said, “stabbed me in the neck, and making a twirl round his fingers with my hair, he commenced sawing and hacking away at my scalp.”

William Thompson was one of the few people to be scalped and live to tell about it. “I can't describe it to you,” he later told a newspaper writer. “It just felt as if the whole head was taken right off.”

Somehow Thompson managed to stay silent, convincing his attacker he was already dead. “The Indian then mounted and galloped away,” Thompson said, “but as he went he dropped my scalp within a few feet of me.”

Thompson grabbed back his scalp and hid in the weeds. He watched the Cheyenne warriors lay more wood across the tracks. He heard a train coming and wanted desperately to jump up to signal a warning, but he was too scared. The train was knocked off the tracks and skidded sideways onto the grass. The Cheyenne shot the men driving the train, then robbed and burned the train cars.

When the Indians rode away Thompson was finally able to get up and look for help. Two days later a reporter named Henry Stanley met him in Omaha. “In a pail of water by his side, was his scalp,” Stanley wrote, “about nine inches in length and four in width, somewhat resembling a drowned rat.”

Doctors in town told Thompson they could sew the scalp back to his head. They couldn't. After a painful failure of an operation, Thompson donated his scalp to the Omaha Public Library (where it was put on display in the children's section).

The Plum Creek attack became famous thanks to Thompson's incredible survival story. But it was just one of a growing number of Indian raids on railroad workers. “We have had a very anxious day of it,” a UP worker named Arthur Ferguson wrote in his diary. “On the lookout from morning until night, not knowing but what we might be attacked at every turn of the road.”

The men running the Union Pacific demanded action from the government. “We've got to clean the damn Indians out, or give up building the Union Pacific,” grumbled Grenville Dodge, the railroad's chief engineer. “The government may make its choice.”

I

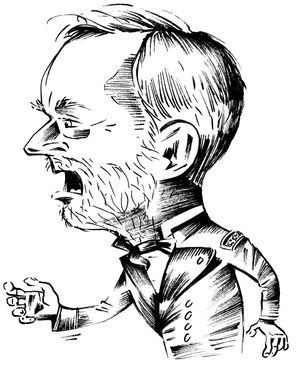

t was an easy choice to make. The government considered the railroad far too important to allow anything, or anyone, to stand in its way. General William Tecumseh Sherman summed up the government's tough stand:

t was an easy choice to make. The government considered the railroad far too important to allow anything, or anyone, to stand in its way. General William Tecumseh Sherman summed up the government's tough stand:

“No interruption to the work upon the line of the Union Pacific will be tolerated. Both the Sioux

1

and Cheyenne must die, or submit.”

1

and Cheyenne must die, or submit.”

William Tecumseh Sherman

While helping lead the Union army to victory in the Civil War, Sherman had gained a reputation for his merciless fighting style. “War is cruelty,” he was famous for saying. “The crueler it is, the sooner it will be over.” In other words:

War sucks, so you might as well get it over with. Don't just attack enemy armiesâburn their homes, destroy their farms, break their will, force them to give up.

War sucks, so you might as well get it over with. Don't just attack enemy armiesâburn their homes, destroy their farms, break their will, force them to give up.

Sherman's strategy had worked against the South. It would work on the Great Plains too. “You should not allow the troops to settle down on the defensive,” he told his generals, “but carry the war to the Indian camps, where the women and children are.” Soldiers attacked villages in winter, burning food supplies and driving survivors out into the snow. The Cheyenne, the Arapaho, and other groups living in the path of railroad had no choiceâthey agreed to move onto reservations further to the south.

T

hen the United States turned its attention to ending Red Cloud's

hen the United States turned its attention to ending Red Cloud's

War, which was still dragging on north of the railroad route. Here the government did something surprising: it admitted defeat. Soldiers abandoned forts along the Bozeman Trail. The road was closed.

Lakota chiefs then agreed to make peace, signing the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868. “The government of the United States desires peace, and its honor is hereby pledged to keep it,” declared the treaty. “The Indians desire peace, and they now pledge their honor to maintain it.”

The Fort Laramie Treaty created what was called the Great Sioux

Reservation. This was a massive chunk (about eighteen million acres) of traditional Lakota land that was forever off-limits to American travelers and settlers. At least, it was supposed to be.

Reservation. This was a massive chunk (about eighteen million acres) of traditional Lakota land that was forever off-limits to American travelers and settlers. At least, it was supposed to be.

For the first time in American history Native American tribes had beaten the United States in a war. Government officials didn't seem too upset, though. For them, the real key was protecting the transcontinental railroad. Sherman's soldiers started guarding the railroad workers as they laid tracks across the Plains.

But would this railroad ever actually be completed?

N

o, judging by the progress of the Central Pacific in California. We haven't checked in on them in a while. We haven't missed muchâthe CP still needed thousands of workers.

o, judging by the progress of the Central Pacific in California. We haven't checked in on them in a while. We haven't missed muchâthe CP still needed thousands of workers.

Here's where the Chinese immigrants come back into the story. By the early 1860s nearly 50,000 Chinese immigrants had arrived in California, almost all of them young men. Chased off the good gold mining spots and forced to pay bogus taxes, they had little chance of making money as miners. They were eager for workâany work.

Charles Crocker (another of the Big Four; weight: 265 pounds) thought it made sense to hire some of these men.

“I will not boss Chinese!” shouted James Strobridge, boss of the CP's construction crews.

“But who said laborers have to be white to build railroads?” asked Crocker.

“I was very much prejudiced against Chinese labor,” Strobridge later admitted.

Crocker convinced Strobridge to try just fifty Chinese workers. “They did so well that he took fifty more,” Crocker reported, “and he got more and more until finally we got all we could use, until at one time I think we had ten or twelve thousand.”

By 1866, Chinese workers (ranging in age from thirteen to sixty) made up about 80 percent of the Central Pacific's entire workforce. True, they had some habits that white workers found weird. They bathed a lot, for example. They sent to San Francisco for seaweed, dried fish, and vegetables, and they drank only tea. Turns out they knew what they were doing. Boiling water for tea killed germs. And the varied diet of fresh food kept them much healthier than other workers, who ate plate after plate of meat and potatoes, sloshed down with muddy water scooped from the nearest stream.

So the Central Pacific had itself a good workforce. But as the men built their way east, they ran smack into the question that had faced Theodore Judah: Was it even possible to build a railroad over the rugged peaks of the Sierra Nevada?

A

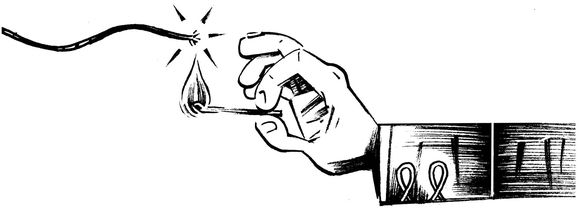

ctually, no. But, with enough courage and patience, it might be possible to build tracks through the mountainsâliterally

through

them. Teams of Chinese workers got the job of carving tunnels through mountains of solid granite. Workers would stand at the top of a cliff and lower other men over the edge on long ropes. Using hand drills, these guys would slowly drill small holes into the side of the mountain. They filled the holes with gunpowder, lit fuses, then jerked on the ropesâthe signal for the men on top to pull them up as quickly as possible.

ctually, no. But, with enough courage and patience, it might be possible to build tracks through the mountainsâliterally

through

them. Teams of Chinese workers got the job of carving tunnels through mountains of solid granite. Workers would stand at the top of a cliff and lower other men over the edge on long ropes. Using hand drills, these guys would slowly drill small holes into the side of the mountain. They filled the holes with gunpowder, lit fuses, then jerked on the ropesâthe signal for the men on top to pull them up as quickly as possible.

Historians haven't been able to find any letters or journals written by Chinese workers on the Central Pacific. But a worker named Wong Hau-hon, who helped build railroads in Canada in the 1880s, described the process of blasting through solid rock. “The work was very dangerous,” he said. The men were under constant pressure to work very quickly, which made the job even riskier. While blasting one tunnel, workers were sent back in before all the gunpowder had exploded.

“Just at that moment the remaining two charges suddenly exploded,” said Wong Hau-hon. “Chinese bodies flew from the cave as if shot from a cannon. Blood and flesh were mixed in a horrible mess.” At least ten men died that day, he reported. We know that accidents like this took the lives of Central Pacific workers as well.

Even with the men taking these terrible risks, progress was painfully slow. “We are only averaging about one foot per day,” complained Charles Crocker.

Then came the snowstormsâworkers counted more than forty of them during the winter of 1866â67. At first the men shoveled the snow off the tracks, dumping it into empty train cars. When cars overflowing with snow rolled into Sacramento (where it hardly ever snows), cheering children raced to the train and started a massive snowball fight.

Up in the mountains the snow kept falling, drifting into piles more than sixty feet high. Rather than quit for the winter, workers dug tunnels down to the tracks and continued working under the snow. The tunnels had stairs and rooms and even blacksmith shops. But the bitter cold and the constant threat of avalanches made them deadly places to work. Central Pacific records include reports that say things such as:

“Snow slides carried away our camps and we lost a good many men.”

“Some fifteen or twenty Chinese were killed by a [snow] slide about this time.”

“A good many were frozen to death.”

As you can tell from these reports, the Central Pacific never bothered to count the exact number of Chinese workers killed on the job. It was certainly somewhere in the hundreds, maybe even the thousands.

Other books

The Ape Who Guards the Balance by Elizabeth Peters

The Winter Ground by Catriona McPherson

Northern Fascination by Labrecque, Jennifer

Materia by Iain M. Banks

Elizabeth Basque - Medium Mysteries 01 - Echo Park by Elizabeth Basque

Love's Deception by Nelson, Kelly

I’m In Lust With A Stripper (Erotica) by Desiree Day

Don't Care High by Gordon Korman

Used to Be: The Kid Rapscallion Story by Bousquet, Mark

The Winter Wolf by D. J. McIntosh