Who Owns the Future? (21 page)

Read Who Owns the Future? Online

Authors: Jaron Lanier

Tags: #Future Studies, #Social Science, #Computers, #General, #E-Commerce, #Internet, #Business & Economics

PRACTICAL OPTIMISM

When science fiction is bright, it brings the gift of helping to sort out what meaning might be like when people are highly empowered by their inventions. Optimistic science fiction suggests that we need not create artificial struggles against our own inventions in order to repeatedly prove ourselves.

In

Star Trek

’s imaginary future,

*

new gadgets don’t just result in a more instrumented world, but also in a more moral, fun, adventurous, sexy, and meaningful world. Yes, it’s pure kitsch, ridiculous on most levels, but so what? This silly TV show reflected something substantial and lovely in the culture of technologists better than any other well-known point of reference. It’s a shame that there aren’t more recent examples to supersede it.

*

This is about the TV series. The qualities praised here are not found in the movies.

An important feature of

Star Trek,

and all optimistic, heroic science fiction, is that a recognizable human remains at the center of the adventure. At the center of the high-tech circular bridge of the starship

Enterprise

is seated a Kirk or a Picard, a person.

†

†

Star Trek

also included artificial intelligence characters, such as the Pinocchio-like Data. The conceit was that Data could not be reproduced. Had there been a billion Datas, his character would have become dull and a threat to humankind, and the whole show turned into a dark tale. It would have become

Battlestar Galactica.

It is almost impossible to believe that the real-world technological optimists of the 1960s, when

Star Trek

first aired, were able to pull off wonders like the moon missions without the computers or materials we have today. Humbling.

There is an interaction between optimism and achievement that seems distinctly American to me, but that might only be because I am an American. Our pop culture is filled with the message that optimism is part of the magical brew of success. Manifest Destiny, motivational speakers, “If you build it, they will come,” the Wizard of Oz giving out his medals.

Optimism plays a special role when the beholder is a technologist. It’s a strange business, the way rational technologists can sometimes embrace optimism as if it were a magical intellectual aphrodisiac. We’ve made a secular version of Pascal’s Wager.

Pascal suggested that one ought to believe in God because if God exists, it will have been the correct choice, while if God turns out to not exist, little harm will have been done by holding a false metaphysical belief. Does optimism really affect outcomes? The best bet is to believe that the answer is “Yes.” I suppose the vulgar construction “Kirk’s Wager” is a workable moniker for it.

I’m bringing up Pascal’s Wager not because of anything to do with God, but because I think the logic behind it is similar to some of the thought games going on in the minds of technologists. The common logic behind Pascal’s and Kirk’s wagers is not perfect. The cost of belief isn’t really known in advance. There are those who think we’ve paid too high a price for belief in God, for instance. Also, you could make similar wagers for an endless variety of beliefs, but you couldn’t hold all of them. How do you choose?

For better or worse, however, we technologists have made Kirk’s Wager: We believe that all this work will make the future better than the past. The negative side effects, we are convinced, will not be so bad as to make the whole project a mistake. We keep pushing forever forward, not knowing quite where we are going.

The way we believe in the future is silly and kitschy, just like

Star Trek,

and yet I think it’s the best option. Whatever you think of Pascal, Kirk’s Wager is actually a good bet. The best way to defend it is to assess the alternatives, which I will do in the coming pages.

The core of my dispute with many of my fellow technologists is that I think they’ve switched to a different wager. They still want to build the starship, but with Kirk evicted from the captain’s chair at the center of the bridge.

If my focus on the culture of technologists is unusual, it’s because we technologists don’t usually feel a need to talk about our psychological motivations or cultural ideas. Scientists who study “pure” things like theoretical physics or neuroscience frequently address the public with books and TV documentaries about the sense of wonder they feel and the beauty their work has uncovered.

Technologists have less motivation to talk about these things because we don’t have a problem with patronage. We don’t need to enchant the taxpayer or the bureaucrat because our work is inherently remunerative.

The result is that the cultural, spiritual, and aesthetic ideas of scientists are a public conversation, while technologists use the rather large slice of public attention we attract primarily for the purpose of promoting our latest offerings.

This situation is more than a little perverse, since the motivating ideas in the heads of technologists have a far greater effect on the world than the ideas that scientists talk about when they exceed the boundaries of their expertise. It is interesting that one biologist might be a Christian while another is an atheist, for instance. But it is more than interesting if a technologist can manipulate urges and behaviors; it is a new world order. The actions of the technologist change events directly, not just indirectly, through discourse.

To put it another way, the nontechnical ideas of scientists influence general trends, but the ideas of technologists create facts on the ground.

PART FOUR

Markets, Energy Landscapes, and Narcissism

CHAPTER 10

Markets and Energy Landscapes

The Technology of Ambient Cheating

Siren Servers do what comes naturally due to the very idea of computation. Computation is the demarcation of a little part of the universe, called a computer, which is engineered to be very well understood and controllable, so that it closely approximates a deterministic, non-entropic process. But in order for a computer to run, the surrounding parts of the universe must take on the waste heat, the randomness. You can create a local shield against entropy, but your neighbors will always pay for it.

*

*

A rare experimental machine called a “reversible” computer never forgets, so that any computation can be run backward as well as forward. Such devices run cool! This is an example of how thermodynamics and computation interact. Reversible computers don’t radiate as much heat; forgetting radiates randomness, which is the same thing as heating up the neighborhood.

There is a fundamental problem with transposing that plan to economics: A marketplace is a system of competing players, each of whom would ideally be working from a

different

, but

not

an a priori better or worse, information position. In a pre-Internet market, it would sometimes be the case that small local players could conjure an informational advantage over big players.

†

†

This book can only present one point of view in a field with many interesting points of view. For foundational ideas about differing access to information in a marketplace, I direct readers to the work of the 2001 winners of Nobel Prize in Economics, who each addressed this topic in a different way:

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/economics/laureates/2001/press.html

.

While it technically need not be so, the Internet is being used to force local players to lose what used to be local information-access

advantages. The reduced portfolio of advantages of locality saps wealth from everyone who isn’t attached to a top server. This problem is related to historic problems that motivated antitrust regulation but it is also distinct.

There doesn’t have to be direct manipulation, but instead an automated, sterile “unintentional manipulation” that seems external to human agency and therefore is above the law. Owning a top server on a network is like collecting rent from the network, but that doesn’t mean one gets there through “rent seeking.”

Traditionally, market positions are set to compete in a pseudo-Darwinian way. Society benefits precisely from the fact that more possibilities will be tested and explored than could ever have been considered from the perspective of a single player, even one with a dominant information perspective.

The rise of top servers as businesses amounts to an ironic intellectual turnaround that gets a pass when it shouldn’t. On the one hand, it is fashionable to overly praise automatic, evolutionary processes in the computing cloud and to underplay the capabilities of the individual, rational mind. On the other hand, it is even more fashionable to praise the success of businesses based on dominant servers, even though the very success of these businesses is based precisely in reducing the degree of evolutionary competition in a market. Individuals are to be underappreciated unless they are connected to the biggest computers on the ’net, in which case they are to be overappreciated.

Imaginary Landscapes in the Clouds

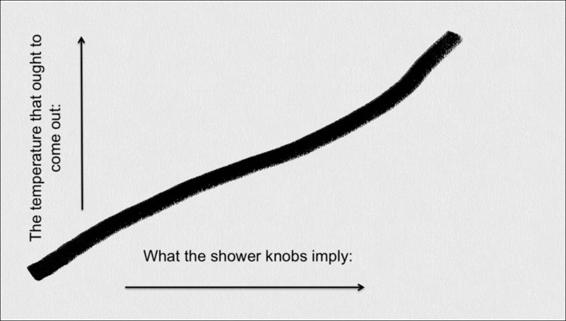

You can think of a marketplace as a form of what’s called an optimization problem. This is the kind of problem where you figure what set of conditions leads to a most desired outcome. For instance, suppose you would like to take a shower with the water at a certain temperature and with the water pressure being just right.

Suppose you have a shower with only hot and cold knobs. Then you can’t set the qualities you want directly. Instead you fiddle with the hot and cold knobs to find the settings that create the shower you want.

There are two inputs, hot and cold. A market can be thought of as a similar system, but with many inputs. The price of each product can be thought of like a knob, for instance. This leads to the idea of a very “high-dimensional” problem, like a shower with many millions of knobs.

Dimensions are a way of thinking about the conditions you are able to set. The hot and cold knobs can be thought of like the X and Y directions on graph paper. Now set a piece of imaginary graph paper down on an imaginary desk in your mind. Imagine that each point on the graph paper sprouts a pole that sticks up—and the height of the pole corresponds to the desirability of the actual temperature and pressure that come out of the shower for particular settings of hot and cold. A forest of these poles will form a sculpture above the graph paper. What will its shape be?

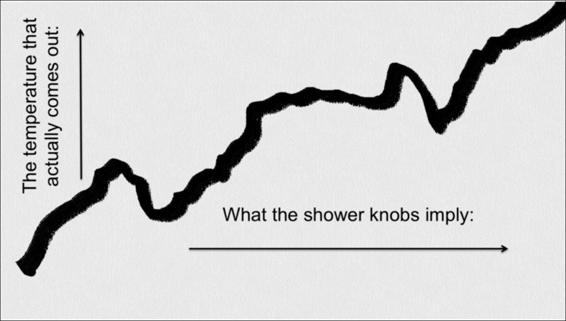

Anyone who has used showers with separate hot and cold knobs knows that finding the right temperature is a little tricky. Sometimes you can move one of the knobs a lot and it doesn’t seem to have an effect. Sometimes the tiniest adjustment has a big effect.

If the knobs always produced consistent effects, then the sculpture would be nice and smooth, but actually, for most showers, the shape will include sudden cliffs. It will be complicated. A picture of the range of outcomes is sometimes called an “energy landscape” because of the cliffs and peaks.

What you might naïvely expect from shower knob positions.