Why We Broke Up (4 page)

“If it’s her, then she probably lives here,” I realized. She was a little away by now, in the coat, with the hat, halfway to halfway down the block. “Nearby, I mean. Someplace. That would be—”

“If it’s her,” you said again.

“The eyes look the same,” I said. “The chin. Look at the dimple.”

You looked down the block and then at me and then at the photo. “Well,” you said, “

this

is definitely her. But the lady down the block, that might not be.”

I stopped looking at her and looked, my God it was beautiful, at you. I kissed you. I can feel it, my mouth on you, I have a feeling now of the feeling I had then, even though I don’t have it anymore. “Even if it isn’t,” I murmured against your neck when it was through—the dry-cleaning customer

ahem

ed us out of her way with her ugly dress exhausted over her elbow, and I pulled away from you—“we should follow her.”

“What? Follow her?”

“Let’s,” I said. “We can see if it’s her. And, well—”

“Better than watching me eat,” you said, reading my mind.

“Well, we could have lunch,” I said, “instead. Or, if you have to, I don’t know. Get home, or something?”

“No,” you said.

“No, you don’t want to, or no, you don’t have to go home?”

“No, I mean yes, OK, if you want to.”

You started to cross back to her side of the street, but I took your arm. “No, stay here,” I said. “We should follow at a discreet distance.” I’d gotten that from

Morocco Midnight

.

“What?”

“It’ll be easy,” I said. “She walks slow.”

“She’s old,” you agreed.

“She’d have to be,” I said. “She’d be something like, I don’t know, she was young in

Greta in the Wild

and that was in, let’s see.” I turned the card over and blinked at a true fact.

“If it’s her,” you said.

“If it’s her,” I said, and you took my hand.

And even if it isn’t

, I wanted to murmur to your neck again, smelling of your shave and your sweat. Let’s go, is what I thought, the movie leaving its vapor trail across my mind. Let’s see where this leads us, this adventure with the thrum of the music and the blizzard of stagy snow, Lottie Carson stalking out of the igloo and Will Ringer grumbling and stamping before, of course, he rouses the dogs and

mush!-mush!-mush!

es to find her so Greta will choose the right man, no matter how humble his igloo, her happy tears freezing to diamonds on her dimple in that light only Mailer could get. Let’s go, let’s go, hurry toward the happy ending with the fur coat of her dreams, pure white polar bear fur Will Ringer tanned

himself, wrapped around her so happy and beaming and snug with the engagement ring a surprise in the pocket just as

THE END

flutters on-screen enormous and triumphant, the big, big kiss. That was the pip for me, chéri. I had a feeling of where it would lead that day,

October 5

, a feeling fanned by the back of this card, the promotional printing of Lottie Carson, a time line with the dates of her life and work. Her birthday was coming up—she was almost eighty-nine. That’s what I thought, moving unaware down the street. December 5 is what I saw as we walked together on October 5, let’s go, let’s go together toward something extraordinary and I started making plans, thinking we would get that far.

If you open this you’ll see it’s empty

, and you’ll wonder for a sec if it was empty when you gave it to me—I can see it—another empty gesture you slipped into my hand like a bad bribe. But the truth, and I’m telling you the truth, is that it was full, twenty-four matches lined up cozy inside. It’s empty now because they’re gone.

I don’t smoke, although it looks fantastic in films. But I light matches on those thinking blank nights when I crawl my route out onto the roof of the garage and the sky while my parents sleep innocent and the lonely cars move sparse on the faraway streets, when the pillow won’t stay cool and

the blankets bother my body no matter how I move or lie still. I just sit with my legs dangling and light matches and watch them flicker away.

This box lasted just three nights, not in a row, before they were all gone and the box held the nothing you see now. The first night was the night of the day you gave it to me, when my mom had finally door-slammed her way to bed and I’d hung up with Al. I was too jitterbuggy happy to sleep, and the whole day kept playing in my brain’s little screening room. There’s a picture in

When the Lights Go Down: A Short Illustrated History of Film

of Alec Matto smoking in a chair in a room with a slice of light blaring over his head toward a screen we can’t see. “Alec Matto reviewing dailies for

Where Has Julia Gone?

(1947) in his private screening room.” Joan had to tell me what dailies are, it’s when the director takes some time in the evening, while smoking, to see all the footage that was filmed that day, maybe just one scene, a man opening a door over and over, a woman pointing out the window, pointing out the window, pointing out the window. That’s dailies, and it took seven or eight matches on the roof over the garage for me to go over our breathless dailies that night, the nervous wait with the tickets in my hand, Lottie Carson heading north on all those trains, kissing you, kissing you, the strange conversation in A-Post Novelties that had me all nerve-wracky after I talked to Al about it, even though he said he had no opinion. The matches were a little

he loves me, he loves me not

, but then

I saw right on the box that I had twenty-four, which would end the game at

not

, so I just let the small handful sparkle and puff for a bit, each one a thrill, a tiny delicious jolt for each part I remembered, until I burned my finger and went back in still thinking of all we did together.

“OK, now what?”

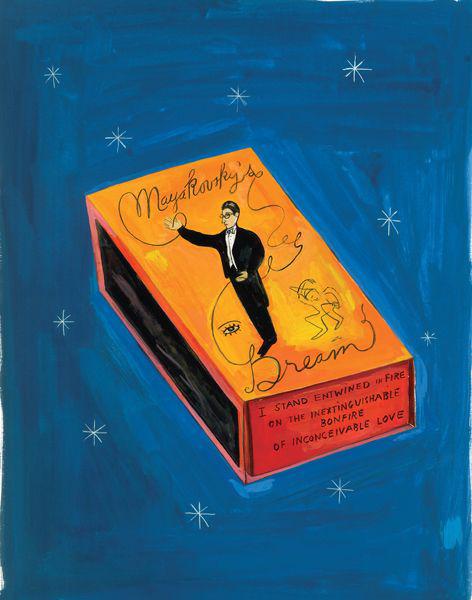

After two blocks Lottie Carson had rounded the corner and stepped into Mayakovsky’s Dream, a Russian place with layers and layers of curtains on the window. We couldn’t see anything, not from across the street.

“I never noticed this place,” I said. “She must be having lunch.”

“It’s late for lunch.”

“Maybe she’s a basketball player too, so she eats all the time.”

You snorted. “She must play for Western. They’re all little old ladies.”

“Well, let’s follow her.”

“In there?”

“What? It’s a restaurant.”

“It looks fancy.”

“We won’t order much.”

“Min, we don’t even know if it’s her.”

“We can hear if the waiter calls her Lottie.”

“Min—”

“Or Madame Carson, or something. I mean, doesn’t this

look like where a movie star would go, her regular place?” You smiled at me. “I don’t know.”

“It totally does.”

“I guess.”

“It does.”

“OK,” you said, and stepped into the street, pulling me with you. “It does, it does.”

“Wait, we should wait.”

“What?”

“It’ll look suspicious to go right in. We should wait, like, three minutes.”

“Sure, that’ll clear us.”

“Do you have a watch? Never mind, we’ll count to two hundred.”

“What?”

“The seconds. One. Two.”

“Min, two hundred seconds isn’t three minutes.”

“Oh yeah.”

“Two hundred seconds couldn’t be three of anything. It’s one-eighty.”

“You know, I remember now you are good at math.”

“Stop.”

“What?”

“Don’t tease me about math.”

“I’m not teasing you. I’m just

remembering

. You won that prize last year, right?”

“Min.”

“What was it?”

“It was just finalist, I didn’t win. Twenty-five people got it.”

“Well, but the point is—”

“The point is that it’s embarrassing, and Trevor and everyone gives me shit about it.”

“I don’t. Who would do that? It’s

math

, Ed. It’s not, like, I don’t know, you’re a really good knitter. Not that knitting—”

“It’s as gay as that.”

“What? Don’t—math’s not

gay

.”

“It is, kind of.”

“Was

Einstein

gay?”

“He had gay hair.”

I looked at your hair, then you. You smiled at some gum on the sidewalk. “We really,” I said, “live in different, um—”

“Yeah,” you said. “You live where three minutes is two hundred seconds.”

“Oh yeah. Three. Four.”

“Stop it, it’s been that already.” You led me in a happy jaywalk across, holding both my hands like a folk dance. Two hundred seconds, I thought, 180, what does it matter?

“I hope it’s her.”

“You know what?” you said. “I do too. But even if it isn’t—”

But as soon as we stepped inside, we knew we should step out. It wasn’t just the red velvet on the walls. It wasn’t just the lampshades, red cloth made rose as the bulbs shone through, or the little glass beads hanging from the shades twirling prismy in the breeze of the open door. It wasn’t just the tuxedos of the men whisking around, or the red napkins folded to look like flags with a little twist in the corner for a flagpole, piled on the corner table for replacements, flags on flags on flags on flags like some war was over and the surrender complete. It wasn’t just the plates with the red script of

Mayakovsky’s Dream

and a centaur holding a trident over his bearded head with one hoof held up to conquer us all and stomp us to meaningless dust. And it wasn’t just us. It wasn’t just that we were high school, me a junior and you a senior, with our clothes all wrong for restaurants like this, too bright and too rumpled and too zippered and too stained and too slapdash and awkward and stretched and trendy and desperate and casual and unsure and braggy and sweaty and sporty and wrong. It wasn’t just that Lottie Carson did not look up from where she was watching, and it wasn’t just that she was watching the waiter, and it wasn’t just that the waiter was holding a bottle, wrapped in a red folded napkin, tilted high over his head, and it wasn’t just that the bottle, iced with a rainy sheen on the neck, was filled with champagne. It wasn’t just that. It was the menu, of course of course, presented on a little podium by the door, and

how much goddamn everything goddamn cost and how much goddamn money we didn’t have on our goddamn selves. So we left, walked right in and left, but not before you grabbed a box of matches from the enormous brandy snifter by the door and pressed it into my hand, another gift, another secret, another time to lean in and kiss me. “I don’t know why I’m doing this,” you said, and I kissed you back with my hand full of matches on the back of your neck.

The night after I lost my virginity, after you dropped me off and after several blank afternoon hours on my bed tired and restless until I sat up and went outside to watch the sun fall on the horizon—that was another seven or eight matches. And then the third night was after we broke up, which was worth a million matches but instead just took all I had. That night it felt that somehow by flicking them off the roof, the matches would burn down everything, the sparks from the tips of the flames torching the world and all the heartbroken people in it. Up in smoke I wanted everything, up in smoke I wanted you, although in a movie that wouldn’t work, even, too many effects, too showy for how tiny and bad I felt. Cut that fire from the film, no matter how much I watch it in dailies. But I want it anyway, Ed, I want what can’t possibly happen, and that is why we broke up.

Across the street

from Mayakovsky’s Dream, right across directly like a Ping-Pong bounce, we hid in A-Post Novelties peeking through the racks of whatnot, waiting and waiting for Lottie Carson to finish her glamorous stop-over and leave so we could follow her home. We couldn’t loiter on the street, I guess, or who knows why we were in A-Post Novelties with the forever grumpy twin hags who run it, and all the nonsense, expensive and bright, people buy for other people for the other people’s birthdays when they don’t know each other well enough to know and find and buy what they really want. This camera is at least the

only thing you got me from A-Post Novelties, Ed, I’ll grant you that. I moved amongst windup animals and dirty greeting cards while you ducked under the mobiles they have until you finally said what it was that was on your mind.