Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (3 page)

For Stone Age settlers the hedgerow was not only a physical barrier between the cultivated land and the wilderness; it was a metaphysical boundary as well. The wild men lived behind the hedges, and the world of ghosts, trolls, goblins, and forest monsters also began there. This was where one encountered the seductive, beautiful, and sly elves. In this place the old deities of the Paleolithic past were still at work.

The archaic hunters and gatherers had been one with the forest, and they had lived in harmony with the forest spirits. In contrast, the forested wilderness was no longer very familiar to the Neolithic farmers and was, in fact, sinister.

1

The Paleolithic goddess of the cave, the protector of the animals and of the souls of the dead, increasingly came to be viewed as a fertile earth mother in the Neolithic period. As with the early Stone Age hunters, the goddess of the farmers appeared to the Neolithic people in visions and sent them their dreams. They also knew that the goddess could hear, feel, and mourn. The fertility of the soil was dependent on her benevolence. Agriculture progressed in a continuous dialogue with her. Plowing and tilling the soil were considered an act of love; impregnating Mother Earth was the religion, and those who impregnated her were the worshippers. In fact, the word

cultivate

originally meant nothing more than service to the gods, honor, sacrifice, and nurturing.

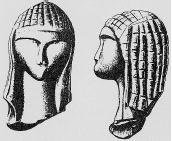

The great Paleolithic Goddess: the Venus of Brassempouy, carved in ivory.

But in spite of worship and ritual, discontent arose and the consciousness of the first farmers was seized with negativity. They defiled the forest, scorched the earth, and laid waste to the soil. The earth goddess became the lamenting mother. She mourned the countless children to whom she had given birth and who had fallen victim to the sickle, the ax, and the spade.

The creation myths of cultivators and farmers always place the violent death, murder, or sacrifice of a divine being at the beginning of their agricultural way of life. The feelings of gratitude and security that permeated the connection between the simple huntergatherers and the forest disappeared into feelings of guilt that had to be ameliorated with increasingly elaborate sacrifices, including gruesome, religiously institutionalized human sacrifices, head-hunting, and cannibalism.

2

Consequently, according to Mircea Eliade, the great scholar of religion, the Neolithic revolution brought about a reevaluation of all values, a “religious revolution” (Eliade, 1993: 45). The Christian concepts of the sacrifice of the innocent son of God and the

mater dolorosa

who mourned him and held him in her lap also have their roots in the myths of the sedentary Neolithic farmers. The community was increasingly guided by the priests, who ruled over the ritual calendar and who determined when to sow and harvest and when to make offerings and sacrifices according to the position of the stars, and less by the shamans, who could talk to the forest and animal spirits.

The unified world of the primitives was gradually separated into two realms: the cultivated land on one side and the wilderness behind the hedgerow on the other; the tame, working animals and the dangerous wild animals; the friendly spirits of the house and farm and the forest spirits one must be careful of. And so the era, which people remember as “golden,” dims—“By the sweat of your brow / you will eat your food / until you return to the ground / since from it you were taken” (Genesis 3: 19).

3

The Power of the Wilderness

The hedgerow that surrounded the clearing was by no means an impenetrable wall. People were conscious of the fact that their small islands of communities, which had been carved out of the primordial forest, were in and of themselves weak and powerless. Thanks only to the boundless power of the wilderness were life and survival possible. From the wilderness came the firewood that burned in the hearth, in the heart of the farm, and with its help the meat was roasted, the soup cooked, and the cold kept at bay from body and soul. Deer, boars, and other wild animals that completed the diet came from the wilderness, as did the medicinal plants and mushrooms that the old women collected. And in a few years, after the fertility of the soil had been depleted, the community had to turn once again to the primordial forest and clear a new place and make it habitable. But the expended earth was taken back into the fold of the wilderness, was overrun with fresh green growth, and her fertility was regenerated.

“To the hill I wended, deep into the wood,

a magic wand to find,

a magic wand found I …”

—

T

HE

L

AY OF

S

KÍRNIR

From beyond the hedgerow came strength. From the wilds came fertility. The human race also renewed itself from one generation to the next through a stream of energy that the dead mediated from beyond the fence. The ancestors came from there seeking rebirth in the circle of the clan. For a long time the hazel tree, a typical hedge tree, was considered a conduit for wild fertile energy from the dimension beyond.

Hazel Tree

(Corylus avellana)

Man has always expected the hazel tree to protect him from the chaotic powers and energies of the beyond, energies such as lightning, fire, snakes, wild animals, diseases, and magic. In the last century the anthroposophists planted a “protection wall” of hazel trees around the Goetheanum

a

to ward off negative spirits. However, it is precisely the dimensions beyond that the small tree connects to. According to René Strassmann, if you fall asleep under a hazel, you will have prophetic dreams (Strassmann, 1994: 174). And the alchemist Dr. Max Amann advised that “contact to friendly nature spirits can be easily gained beneath hazel branches.”

Hazel branches had probably already been used by Stone Age magicians to tap into the powerful energies of the world beyond and transmit them to the everyday world. It then becomes clear why the magical stave with the snake coiled around it, the caduceus of Hermes (the shamanic god of antiquity who crossed boundaries), was cut from a hazel tree. This stave became the symbol of trade, medicine, diplomacy, and the river of Plutonic energy that revealed itself in precious metals (money). When Hermes touched people with the hazel branch, they could speak for the first time.

Dowsers still consider hazel branches to be the best conductors of energy. With them dowsers can detect the sensitive water veins in the earth, as well as precious metals (silver and gold). The ancient Etruscans knew of dowsers

(aquileges)

who were able to find buried springs with hazel branches. The Chinese feng shui masters of more than five thousand years ago also knew how to use these wands in order to detect the flow of the “dragon lines” in the earth. Hazel branches still work today for this purpose, and are much faster and cheaper than technical instruments.

The ability to influence the weather is a shamanic trait recognized throughout the world. The ancient European shamans used hazel branches in order to make rain; such weather-makers still existed in the Middle Ages. A law from a seventeenth-century witch trial reads, “A devil gave a hazel branch to a witch and told her to beat a stream with it, upon which a downpour followed.” It also says, “A witch-boy flogged the water with a hazel switch until a small cloud rose up from it. Not long thereafter a rainstorm began” (Bächtold-Stäubli, 1987: vol. 3, 1538).

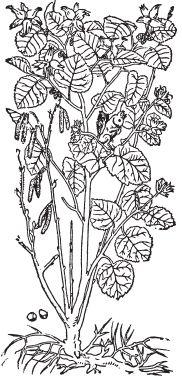

The hazel bush (

Corylus avellana

L.) has always been considered a magical tree and an important remedy in witches’ medicine. The writers of antiquity already attributed magical powers and rare effects to the “pontic” (bitter) nut. Dioscorides said that “the eyes of blue children can be colored black by rubbing the oil of roasted, finely grated shells on the forehead” (

Materia medica

I.179). (Woodcut from Hieronymus Bock,

Kreütterbuch,

1577.)

Hazel energy can also be used to subdue nasty weather. When there is too much thunder and hail, farm women of Allgäu throw a few hazel catkins from the bunches of herbs that were blessed on Ascension Day (August 15) onto the hearth fire. And didn’t Mary, when she wanted to visit her cousin Elizabeth in the mountains, seek protection from a storm under a hazel tree? People today still know that the hazel has something to do with fertility. To “go into the hazelwood” means nothing other than to copulate. “Anneli, with the red breast, come, we’ll wend our way into the hazelwood,” goes a Swiss folk song. “Easy” girls are given a hazel stick during the May Festival. In the symbolic language of the Middle Ages the hazel was considered to be the “tree of seduction.” A Moravian song warns a virgin about the dangerous tree:

Protect yourself, Lady Hazel, and look all around,

I have at home two brothers proud, they want to cut you down!

The unconcerned Lady Hazel responds:

And if they cut me down in winter, in summer I’ll green again,

But when a girl loses her maidenhead, that she’ll never find again!

It is no wonder that the nun Hildegard of Bingen did not speak particularly highly of the hazel: “The hazel tree is a symbol of lasciviousness, it is rarely used for healing purposes—when, then for male impotency.” In those days a hazel branch was hung over the bed of a married couple as a remedy for infertility. And as a sign that they were hoping for the best, the couple carried with them hazel branches pregnant with nuts.

“When there are hazelnuts there are also many children born out of wedlock.” “When the hazelnuts prosper, so do the whores.” Such sayings are found throughout Europe. Ethnologists trace them back to the fact that the youth escaped the suspicion of the guardians of public morals when they were out collecting nuts in the forest. More likely there is another explanation—people who are bound to nature determine themselves instinctively on and are part of the fertility rhythms of the forest.

Our forefathers believed that the ancestral spirits conveyed the unspent energy from the wilderness and the beyond to the living. It was the spirits who sent babies and who blessed the fields with fresh green life. Among the northern European heathens, many midwinter rituals included boys wrapped in fur pelts who raided the villages and flogged people and animals with hazel branches. The boys embodied the ancestral spirits. The Celtic god of winter, Green Man, who visited the houses, hearths, and hearts of the people during the winter solstice, also carried hazel branches, whose lash made everything fertile, prosperous, and rich with milk.

But the living could also send essential nourishment to those on the other side.Since Neolithic times hazelnuts have been “fed” to the dead by pressing a nut into their hands or between their teeth. The dead Celts, like the Chieftain of Hochdorf, Germany (from the Hallstatt period), were laid to rest on hazel branches. In November, on the ancient Celtic festival of the dead, children dressed as spirits of the dead and ghosts went begging from house to house. They were given the seeds of life—hazelnuts and apples—which lasted throughout the winter. The Germanic tribes, in particular the Alemanni, stuck sticks of hazel on grave sites.

It was believed that those who found the

Haselwurm

—a creature half human, half snake—and ate its flesh would attain extraordinary powers.