Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (5 page)

The birch tree (

Betulas

pp.) is generally considered the tree that supplied the branches that were bound together to make witches’ brooms. The “witch’s broom” was originally a shamanic spirit horse, a heathen wand of life (a symbol of fertility), and was used as a magical bundle during sacred ceremonies and for the protection of the house. Parasitical growths on the branches of the Moor birch (

Betula pubescens

Ehrh.) caused by an invasion of a fungus

(Taphrina betulina)

causes deformations that are still referred to as “witch brooms” in botanical literature. (Woodcut from Hieronymus Bock,

Kreütterbuch

, 1577.)

The birch is the ultimate shamanic tree. The Eurasian shamans ascend the consecrated, decorated birch when they visit the spirit world. Their masks are carved from birch bark; their familiars are cut from birch wood. The frame-drum stretched with the hide of a wild animal is made from birch wood, preferably one that was struck by lightning. The Siberians say that the cradle of the original shaman stood beneath a birch tree, and that birch sap dropped into his mouth.

The dead are also concealed and protected by the birch. The Ojibwa wrap their dead in birch bark. The Jakuten used it to surround the head of bagged bears. The Celts placed a conical birch hat on the dead, as they did, for instance, with the Chieftain of Hochdorf or the warrior of Hirschlangen. There is an old Scottish ballad about dead sons who appeared to their mothers wearing birch hats on their heads; the hats are a sign that they will not hang around as ghosts, but will return to the heavens.

In May, when everything is blooming and budding, the radiant sun god came from the heavens to celebrate with his beautiful bride, the flower goddess. With great revelry the celebrants brought the sun god from the forest or the nearby holy mountain—later from the sacred grove or from a cavelike temple. The divine couple took tangible form in the maypole—usually a birch that has been stripped of its bark—and another one decorated with painted eggs, red ribbons dipped in sacrificial blood, flower garlands, and other votive offerings. Sometimes the gods were also embodied in the lavishly adorned May Queen and May King, the prettiest maiden and the strongest boy in the village. They were usually received with frenzy and wild orgies. How could it be any other way? The immediate presence of the divine robs humans of their reason! The heirs of the Neolithic and Bronze Age farmers continued to celebrate the May Queen, whom they decorated with flowering hawthorn.

Midsummer’s Dream

During the period of the summer solstice, the days are so long that it was once believed that the sun was standing still. Again the people were nearing the divine: The sun god and the great goddess, pregnant with the powers of heaven, were seen in the ripening grains and fruits of the forest and field. The mighty thunder god, Thor, who brings the summer storms, was also there. Dancing elves and throngs of ethereal sylphs and fiery salamanders appeared as well. And as usual when the numinous nears, humans fall into ecstasy.

Mugwort

(Artemisia vulgaris)

was one of the most important ritual plants of the Germanic peoples. Fresh bundles of the herb were stroked over the sick person and then burned to dispel the spirits that brought disease. Mugwort is one of the most ancient incense herbs in Europe. Mugwort is also considered to be an herb of Saint John. (Woodcut from Hieronymus Bock,

Kreütterbuch,

1577.)

Elements of the archaic summer solstice customs have been retained throughout the agricultural regions, and if we reached into the deep layers of our own souls, we could paint a reasonable picture of what the celebrations were like. Like the winter solstice, the summer festival lasted a full twelve days. The people took in the fullness of the light and the power of the fire and enhanced their experience with the solstice fire, with fire-walking, with burning brooms and torches, and by rolling wheels of fire down the mountains and hills. With the fire they celebrated the apex of the year but at the same time they celebrated death, the sacrifice of the sun god, of fair Balder, as he is called in Scandinavia.

In Wales and elsewhere nine types of wood were gathered for the solstice fire.

4

Either respected elders or a young couple lit the fire. Dried mugwort, the healing and “hot” herb, which played a sacred role in midsummer festivals all across the northern hemisphere, was placed on the fire, creating a raging and high violet-colored flame (Storl, 1996a: 45). The celebrants jumped through this fire one after the other or holding hands; the goddess herself—Frau Holle, Artemis, Dea-Ana, or whichever name she was called by—was present in the mugwort. They jumped over the purifying flames wrapped only in a mugwort girth with a wreath of ground ivy in their hair and vervain in their hands, leaping from one season through to the next. The companion and paramour of the goddess, the thunder god with the mighty hammer, was represented in the ground ivy and the vervain.

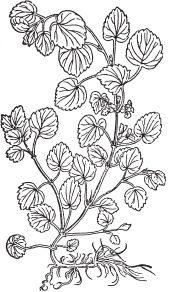

Ground ivy (

Glechoma hederacea

L.,

Nepeta hederacea

[L.] Trev.) is an edible wild plant; it is particularly good in a spring salad and “Thursday’s green soup.” This Germanic hedgerow plant is bound into garlands that are used to detect and reveal witches on Walpurgis Day (May 1). Ground ivy is also said to have the power to protect milk from spells or free it from curses. The women of Aargau sew ground ivy into the hems of their skirts for fertility magic. The herb is used in folk medicine to stimulate the production of milk, for wounds, to chase away the “tooth worm,” and as an abortifacient. (Woodcut from Hieronymus Bock,

Kreütterbuch,

1577.)Mugwort

(Artemisia vulgaris)

was one of the most important ritual plants of the Germanic peoples. Fresh bundles of the herb were stroked over the sick person and then burned to dispel the spirits that brought disease. Mugwort is one of the most ancient incense herbs in Europe. Mugwort is also considered to be an herb of Saint John. (Woodcut from Hieronymus Bock,

Kreütterbuch,

1577.)

The people of today, who largely shield themselves from nature, find it difficult to comprehend the ecstasy of midsummer, of being unconditionally swept along with the natural occurrences. As recently as the Middle Ages, the most incredible rumors could be heard. It was as if one had stepped into a painting by Hieronymus Bosch—the sun produced three springs, water turned into wine, elves disclosed hidden treasure, horses could talk, music sounded out of the mountain, and ghost processions, water nymphs, and fairies became visible. White maidens revealed themselves or else asked to be released from confinement, dwarfs celebrated marriage, serpents honored their king, the fern bloomed at midnight and carried seeds (which bestowed invisibility and wealth on the one who found them), crabs flew through the air, and the Bilwis

d

rode a fiery buck over the fields.

What kinds of visions are these? They are pictures of the inner realm of nature. Were they induced by the henbane beer that was drunk in copious amounts? Was the endless dancing, the hours upon hours without sleep responsible? Or maybe it was the hallucinogenic mushrooms, such as bell caps, haymaker’s mushroom, liberty caps, fly agaric, and others, that transported the people? After all, in the Middle Ages Saint Vitus’s Day (June 15) was considered the beginning of midsummer—“here the sun will go no higher!”—and Saint Vitus is the patron saint of mushrooms. The Slavs say that he is accompanied by good gnomes who help the mushroom to grow well. Saint Vitus was also invoked for fainting sickness and rabies, which occurred again and again in the Middle Ages.

5

During these “psychological epidemics” the people had a burning desire to form a circle and dance until they were overcome with total exhaustion.

For many years it was believed that witches picked their herbs at the summer solstice, and that they did it naked in the middle of the night. The farm women also made a bouquet of midsummer herbs, a summer solstice bundle, from one of the countless versions of nine herbs—a magic number. To increase the healing power of yarrow, wood betony, or other herbs the women peered through the bundle into the fire and spoke a charm, something like the following: “No boil shall come on my body, no break to my foot.”

It is a heathen custom to strew carpets of flowers and aromatic herbs on the ground at the solstice for the gods to rest on. Love nests were also prepared in this way. With the Christian conversion this carpet of flowers became known as

Johanistreue

(Saint John’s bedstraw),

e

the bed upon which John, the favored disciple of Jesus, lay down to rest, the intention being to mix that same loyalty into the love nest. The mugwort belt became the belt that John the Baptist was said to have carried through the desert.

The plants considered to be midsummer herbs differed from region to region, but they almost always included the following:

Ferns have a long history in witches’ medicine. It is said that the fern can make one invisible, and that the seeds, preferably harvested during the night of Midsummer’s Eve, bring luck and magically increase one’s wealth. However, the fern is also feared as a “crazy herb” and is classified in the nocturnal realm of the witches and devil. There are even different indications of the psychoactive species of ferns. (Woodcut from Otto Brunfels,

Contrafayt Kreüterbuch,

1532.)

Saint John’s wort

(Hypericum perforatum)

is one of the most important herbs of midsummer. (Woodcut from Otto Brunfels,

Contrafayt Kreüterbuch,

1532.)