Read Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants Online

Authors: Claudia Müller-Ebeling,Christian Rätsch,Ph.D. Wolf-Dieter Storl

Witchcraft Medicine: Healing Arts, Shamanic Practices, and Forbidden Plants (4 page)

Fertility is not the only gift from the other world. The kind of wisdom that far exceeds the boundaries of ordinary human understanding also comes from there. The hazel tree makes this knowledge available to the living; it helps them to crack the hardest “nuts” (riddles). Celtic judges carried hazel branches. The ancient heralds, who strode over borders like Hermes, also carried such staves so that their words would be intelligent and well chosen. The Germanic tribes stuck hazel branches in the ground around the

Thingstead,

the place where the tribal council was held and where duels took place. In this way the thunder-god, Thor, whose hammer symbolizes justice, was present. The hazel branches were sacred to this god of fertility and of the life-giving rain, who was the protector of the earth’s treasures and the vanquisher of the snakes. The hidden treasures Thor found with his magic wand also belonged to him; presumably the handle of his hammer was made of hazelwood. The shamanic god Odin (Wodan, Wotan), lord of the bards and magicians, also made use of the hazel branch. The magical wand sacred to him was cut from the hazel tree and carved with reddened runes on Wodan’s day (Wednesday). The hazel is also said to be the enemy of snakes. Saint Patrick, the patron saint of Ireland, allegedly used a hazel stick to chase all the snakes off the green island. In the Black Forest region children who had far to travel were given hazel branches so that they would be safe from snakes. And if a circle is drawn around a snake with a hazel branch, the snake cannot escape.

In addition, the

Haselwurm,

a white serpent with a golden crown, was believed to live under a very old hazel tree, one that had been invaded by a mistletoe. Eye witnesses described this snake queen as half human, half serpent. She had a head like an infant or a cat and she cried like a child. She was called the “serpent of paradise” in the Middle Ages, because she was believed to be the same snake that had seduced the humans in paradise. Nevertheless, those who find this snake and eat of her flesh will receive wondrous powers: They will have command over the spirits, they will have the ability to become invisible, and they will know all of the hidden healing powers of all herbs. Paracelsus was said to have eaten such a snake, and “that is why when he went out into the fields the herbs spoke to him and told him which evils and illnesses they were effective for.” Naturally, it is not easy to capture this snake. One should go before sunrise on a new moon. And the right spells must be spoken: one that addresses the hazel branch and one that charms the snake. So that the snake will remain quiet, dried mugwort must be strewn on the magical creature.

This mysterious serpent is connected to the archaic brain stem, including the entire limbic system, which appears in the minds of those deep in meditation (the crowned snake-head). The instincts are anchored here in this most ancient part of the nervous system. Sexuality, fertility, premonitions, and emotions have their physiological basis here as well. The hazel is able to transmit subtle impulses to this center.

Divine Visitors to the Small Cultural Island

The gods also came from beyond, from deep in the forest. They came to demand tribute from the people and to bless and inspire them. For a long time into our own era, the “spirit of life,” decorated with the branches of fir and holly trees, strode through the snowy winter forest on the solstice. The spirit blessed the animals in the forest and those in the barn before he made the humans happy with visions of the newly ascending light of life. This light-bringing spirit lived on in the Christ child, who came at midnight, as well as in Santa Claus. The spirit comes from far away, from the North Pole or from the dark, saturnine conifer forests. Often he flies like the shamans, with a sleigh drawn by reindeer, or rides an elk, or sometimes he even walks. A merry band of elves accompanies him. He slips down the chimney in the deep of the night to touch the sleeping people with his life-dispensing hazel wand and leave good fortune in their shoes, which have been set out.

Those from beyond, the transsensory beings, also came through the hedgerow so as to spend awhile with the humans during periods determined by the arc of the sun, the phases of the moon, and the weaving of the constellations. During the full moon of February the white virginal goddess of light left the caves with her bears and a retinue of elementary spirits. She woke up the bees and the seeds, which were still sleeping under a blanket of snow, and shook the tree trunks so that the sap would flow anew. For her appearance Stone Age people prepared themselves with a cleansing sweat lodge. Fermented birch sap sweetened with honey provided great happiness. Seized by the awakening spirit of life, stirred by the dancing and singing elemental beings, the people began to dance wildly and make faces. The disease-bringing spirits—usually crippled, knotty figures with angry expressions—were also honored and sent back into the woods with small offerings.

The Alemannic

Fastnacht

(Shrove Tuesday) celebrations, with their wild man and their witch’s dance, is an echo of the ancient nature festivals. These processions of horrifying and beautiful

Perchten

b

who visit the human settlements during this time of year visually represent much transsensory wisdom. The first day of February, known today as Candlemas, was celebrated as the Imbolc festival in honor of the birch goddess by the insular Celts. As one of the quarter days, it is still considered to be a witch’s holiday.

Birch

(Betula)

The spirit of the birch tree appeared to the archaic humans as a virgin veiled in light, full of magical and healing powers. The original Indo-Europeans called this benevolent goddess and friend to man Bhereg, meaning “wrapped in brilliance.” To this day the birch tree is called this, in different variations, throughout Germanic-, Slavic-, Baltic-, French-, Spanish-, and Celtic-speaking regions. It has always been endowed with qualities of purity, light, and new beginnings.

The Celts saw Brigit, the muse of the seekers of wisdom, the healers, and the inspired bards, in the birch. She is the white virginal bearer of light who lets the days grow longer again in February. During this prespring period, the primitive people tapped the birches and collected precious sap. The sap stimulates urine and bile, purifies and cleanses the blood, and strengthens the kidneys and urinary tract.

“Be joyous birch trees, be joyous green ones! The maidens are coming to you, bringing you cakes, bread, and omelets.”

—OLD

R

USSIAN SONG

The tree of light reminded the Slavic and Siberian peoples of white-feathered swan maidens. Sometimes these women wed shamans and lent them their wings, which carried them into the etheric dimensions. The German peoples thought about Freya in her delightfully sparkling necklace

(Brísingamen)

when they saw this tree. They also associated the tree with Bertha, “the radiant.”

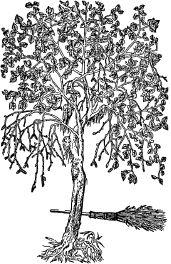

The birch tree (

Betulas

pp.) is generally considered the tree that supplied the branches that were bound together to make witches’ brooms. The “witch’s broom” was originally a shamanic spirit horse, a heathen wand of life (a symbol of fertility), and was used as a magical bundle during sacred ceremonies and for the protection of the house. Parasitical growths on the branches of the Moor birch (

Betula pubescens

Ehrh.) caused by an invasion of a fungus

(Taphrina betulina)

causes deformations that are still referred to as “witch brooms” in botanical literature. (Woodcut from Hieronymus Bock,

Kreütterbuch

, 1577.)

In the distant Himalayas the birch (Sanskrit:

Bhurga

) is worshipped as the radiant white goddess, whose vehicle is a white swan or a goose. Saraswati—as she is called there—inspires the humans with wisdom and knowledge, with the arts of writing and oratory. She brings everything into flow, and brings the river of healing and poetic inspiration. She too appears to the people in February, when whole throngs of schoolchildren and their teachers get dressed up and carry her image through the streets. The first books in which the Vedic sages wrote their visions were made from the bark of birch trees. In Europe the birch was also considered to be a tree of learning. During antiquity children were taught the joys of learning with birch whips.

Like the white virginal goddess herself, the birch represents beginnings. She is young and fresh, like a blank page upon which the future can manifest itself. Birch green symbolizes the promise of a new spring. At the start of the agricultural year, the northern European farmers placed birch branches on their fields and buildings. The first time the cows were let out to pasture they were driven along with birch sticks or herded over birch branches. The farmers “flog,” “slap,” or “beat” everything that is to flourish. The virgins are not spared, and are driven from their beds with laughter. The birch stands for the beginning of love. In pre-Christian times smitten boys would place fresh green birch twigs in front of the house of the one they were courting. The young people danced merry round dances beneath the maypole, which was a decorated birch tree. And when Freya blessed love with the birth of a child, the placenta was buried beneath a birch tree as an offering to the goddess. The crib, the first bed of a new citizen of the earth, was to be made from birch wood as well.

Naturally, the druids made the birch

(Beth)

into the first letter of their tree alphabet

(Beth loius nion)

and the first month of the tree calendar. Robert Graves believed that this month went from December 24 to January 20 (Ranke-Graves, 1985). But because the Celtic calendar was a fluid moon calendar that went from new moon to new moon, such an exact calculation of time is doubtful. It is possible that the birch month commenced with the appearance of the “virgin of light” in February.

The Germanic tribes knew of a birch rune ( ) that transmits the feminine growing energy of spring. At least that is what my friend Arc Redwood—an English gardener who carved this rune in wood, reddened it, and placed it in his garden like an idol—believes. He claims this has caused everything in his garden to grow better.

The birch tree is a sign of new beginnings not only in a cultural sense, but in nature as well. The cold-hardy tree was the first to seed itself on the ground after the glaciers receded. The Stone Age people were able to survive with its help. Archaeological digs show that Paleolithic hunter-gatherers used birch gum to secure their arrowheads and harpoons to the shaft. Shoes and containers were made from birch bark, and clothing was made from the bast fiber. “Ötzi,” the Neolithic man who was found frozen in a glacier crevasse, also carried a bag made out of birch bark. The Native Americans and Siberians still carry birch-bark containers like our Stone Age ancestors once did. Maple syrup can be stored for a whole year in such containers. The inner bark could be eaten in an emergency, and in the springtime people tapped the sweet sap, which was occasionally left to ferment into an alcoholic drink. The birch is still the most important tree to the Ojibwa Indians. They decorate their wigwams and make everything from canoes to spoons, plates, and winnowers for wild rice from the birch bark. They even make watertight buckets and cooking pots with the bark. Glowing hot stones are placed in the sewn and resined birch-bark pots for cooking.

The birch tree stands for purity. Shrines and sacred sites were ritually swept with a birch broom to encourage evil ghosts to depart. In later times the ritual broom became the witch’s broom; witches used it to fly to Blocksberg. The birch broom is occasionally used in England to fight against invisible flying astral spirits (witches) or the lice and fleas brought in by them. The old year is also swept away with a birch broom. In ancient Rome the lectors carried bundles of birch branches tied with red cord when swearing a magistrate into office. A bundle of birch branches with an ax in the middle is known as a

fascis,

and is considered the sign of the cleansing rule of the law. Italy’s “Mr. Clean,” Mussolini, appropriated this symbol for his fascist movement.

In the vicinity of the small farm where I live there is a “broom chapel.” Like other such chapels in the Alemann region, it is dedicated to the patron saint of the plague, Rochus. If any of the inhabitants suffer from skin diseases, one of the family members takes it upon herself to make a pilgrimage to this chapel and pray for healing. A broom made from birch branches must be brought along as an offering. Just a few years ago there were still dozens of such brooms in this chapel.

Birch branches belonged to the inventory of the Stone Age sweat lodge, as they still do in saunas and Russian sweat baths. The whipping of the overheated body is considered to be healing and cleansing. The Native Americans of the Great Lakes region place birch bark, which contains volatile oils, on glowing stones to cleanse the lungs and skin during the sweat lodge ceremony.

The archaic peoples associated the birch with light and fire. They made brightly burning torches out of dried rolled birch bark. But this is not the only connection between fire and birch. The tinder polypore

(Fomes fomentarius),

which grows mainly on birch trees, is more suited than almost any other material for making fires. For this a stick of wood, usually an ash branch, is spun so quickly that the fungus, which is used as the base, begins to glint and catch fire. In the imagistic minds of the primitive peoples, this was a sexual act in which the birch fungus represented the feminine, firebearing womb—another connection to the light-bearing goddess!

Healers in the New World as well as the Old place small burning pieces of coal made of tinder polypore (moxa, punk, touchwood) on painful areas. Such pieces of fungus coal are found in the archaeological digs of the settlements of the Maglemose people, who lived more than ten thousand years ago in northern Europe. Hildegard of Bingen reached back to this healing method from the Stone Age, prescribing charcoal made from birch bark for the back, limbs, and internal pain. The poison or the disease-bringing spirit was then able to exit through the resulting burn wound.

Another mushroom is symbolically associated with the birch: the psychedelic red fly agaric

(Amanita muscaria).

With its help the shamans of the northern hemisphere climb up the inverted Tree of Life, all the way to the roots, in order to visit the gods and ghosts. (In many cultures elements of the “other world” are upside down or backward in relation to this world.) In this context the connection to light is also apparent; in Siberia fly agaric is often called “lightning mushroom.” It is taken only at night, and it causes entopic light phenomena that resemble lightning flashes. Thus we can understand why the northern Germanic peoples consecrated the birch not only to Freya, but to the storm god Thor as well. Manabozo, the cultural hero of the Ojibwa, found protection from the projectiles of the thunder god in a hollow birch tree; since that time these Native Americans use birch incense to soothe or scare off the lighting hurler. The farmers of Allgäu also burn birch branches left over from the

Fronleichnamumzug

c

when the stormy weather has lasted long enough. In the Protestant regions, on Whitsunday (Pentacost)—the day when the Holy Spirit appeared to the faithful in the form of a tongue of flame—buildings and vehicles are decorated with fresh birch leaves.