Written in Blood (13 page)

Authors: John Wilson

Tags: #Historical, #Young Adult, #book, #Western, #JUV000000

The next morning I drag the bodies away. Animals have been at some of them, but I don't have the strength to bury them in the hard ground. I simply pile them into a storeroom that still has a door on it. I find Alfonso Ramirez's scalp by the fireplace where Ed must have dropped it when I charged him. I throw it into the storeroom with the others. Then I ride into town.

I buy us some supplies, food for us and the horses and clean clothes. I must look pretty bad, because people stare and give me a wide berth as I go about my business. It's obvious that I'm in pain from my ribs, but no one offers to help. There is a

medico

in town, but I don't bring him out. I wonder if he'll treat a wounded Apache. He doesn't speak much English, but in my halting Spanish I ask him to put together a bundle of bandages, swabs and ointments.

When I return to the hacienda in the afternoon of the second day, Nah-kee-tats-an is running a fever. He's lying by the stove, wrapped in a bedroll, shivering and sweating. I try to keep him cool and feed him something, but by nightfall he's delirious and speaking loudly in his native tongue. Eventually, toward dawn, he quiets down and I sleep.

I wake up in full daylight with the local medico standing in the doorway staring at Nah-kee-tats-an.

“

Ãl es enfermo

,” he says unnecessarily.

“Yes, he is sick,” I reply.

The man bustles forward and crouches over Nah-kee-tats-an. He examines the recent wound and the one from the ambush several days ago, nodding and speaking softly to himself. Occasionally he addresses me with a request. “

Agua caliente, por favor

.” I busy myself with the fire, heating water and cooking some food.

At last the medico stands up. He insists on looking at my injuries and binds a wide strip of cotton tightly round my chest. It helps the pain when I move. He hands me some more of the ointment and instructs me in applying it and changing Nah-kee-tats-an's dressings. Already, my friend seems to be sleeping more easily.

I offer the man some breakfast, and we eat in silence. After we are done, he walks through to the main hall and stands looking at the several large dried bloodstains.

“ Dónde están los cadáveres?

Dónde están los cadáveres?

” he asks.

I take him to the storeroom and haul open the door. A cloud of large flies rise with a loud buzzing sound. The medico simply nods. He walks over to where I have tethered the horses I have managed to catch. Coronado is there, as is an unsaddled pony that belongs to Nah-kee-tats-an. I have also caught Ed's large black gelding and two other animals. The other two are nowhere to be seen.

“ Estos caballos pertenecen a los cadáveres?

Estos caballos pertenecen a los cadáveres?

” the medico asks.

I tell him that, apart from Coronado and the pony, these horses

do

belong to the dead men. He asks me if I will give him those horses to sell to pay for the medicine. I say sure and he ties the horses to his wagon and leaves.

The next day, two men with shovels turn up and bury the bodies. They cross themselves a lot as they work and stay well away from me and Nah-kee-tats-an, whose fever has broken and who is taking some food.

On the fifth day the medico returns, examines us both and pronounces himself satisfied with our progress. Nah-kee-tats-an is sitting up. He regards the medico suspiciously but allows him to work on his wounds. The medico gives us some more supplies, a bag of feed for the horses and a small bag of silver coins from the sale of the horses. Outside he turns to me as he prepares to mount his horse.

“ Usted conoce esta casa?

Usted conoce esta casa?

” he asks.

I say that I do know this house. “

Es la casa de Ramirez

.”

The medico nods. “

Mala suerte. Es una casa de la muerte

.”

“Yes,” I agree. It a place of bad luck and death. On an impulse I ask, “ Usted conoce Luis Santiago de Borica?

Usted conoce Luis Santiago de Borica?

”

The medico's face brightens into a smile at the mention of Santiago. “

SÃ. SÃ. Ãl es un buen hombre.

”

I agree that Santiago is a good man and tell the medico of my evening with him. Then I tell him he is a good man and thank him for his help. “

Gracias por su ayuda

.”

“

No es nada

.” The medico shrugs off my gratitude and mounts. “

Vaya con dios

.”

I wave as he rides out the hacienda gate.

“I will leave in the morning,” Nah-kee-tats-an announces as we sit by the stove after our evening meal.

“Are you well enough?” I ask.

Nah-kee-tats-an nods. “And I have lived within walls long enough.”

“Where will you go?”

“I will find Victorio and fight with him.”

“Your father, Too-ah-yay-say, says there are too many Americans. He thinks you cannot win.”

“But that does not mean we should not fight. You and I fought here against the scalp hunters, and now they are dead and we are alive.”

I nod agreement. “Why were you here?” I ask the question that's been nagging at me.

“I was trailing the men who scalped my friends. When I saw they were coming here, I climbed in a window at the back and waited.”

“I'm very glad you did.”

“What will you do, Busca?” Nah-kee-tats-an asks.

I haven't given it much thought. I've been too focused on finding out what happened to my father and on simply surviving. Suddenly I know what I must do. Many people have helped me on my journey by telling me their stories, which have turned out to be parts of my story. I will return the way I came and tell Santiago and Wellington how the story ends. And I will write a letter to my mother in Yale. I won't go back up to British Columbia. Not now. I'm not ready and, if I am honest, this harsh land fascinates me. I feel it is not done with me yet.

“I will tell a story,” I reply.

My vague answer seems to satisfy Nah-kee-tats-an.

“Perhaps, one day,” he says, “our stories will cross again.”

When I wake the next morning, Nah-kee-tats-an is gone.

In no great hurry, I make breakfast, pack up my few belongings, saddle Coronado and leave the bloodstained hacienda behind. I am sad that my father is dead and that I never got to see him again, but I feel relieved that I know. It's as if a huge weight has been lifted from me. I'm free at last.

JOHN WILSON

is the author of twenty-nine books for juveniles, teens and adults. His self-described “addiction to history” has resulted in many award-winning novels that bring the past alive for young readers. Wilson spends significant portions of the year traveling across the country speaking in schools, leaving his audiences excited about our past. You can learn more about John, his books and his presentations by visiting his blog: [email protected].

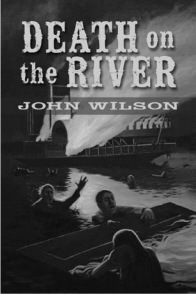

The following is an excerpt from another

exciting novel by JOHN WILSON.

978-1-55469-111-1 $12.95 pb

978-1-55469-257-6 $18.95 hc

C

APTURED AND CONFINED

to the Confederate prison camp at Andersonville in June 1864, young Jake Clay forms an unlikely alliance with Billy Sharp, an unscrupulous opportunist who teaches him to survive no matter what the cost. By war's end Jake is haunted by the ghosts of those who've died so he could live. Now his fateful journey home will come closer to killing him than Andersonville did, but it will also provide him with one last chance at redemption.

ONE

I

pull back the thin blanket and swing my legs over the edge of the bed. When I stand up, the tiled floor feels icy cold on my bare feet, but that's goodâit reminds me that I'm alive.

There's a pile of clothes on the table by the bed. They're not mine; they were dropped off by a smiling nun who went round the ward asking if any of us needed anything. I said I wanted clothes and a pair of shoes, and her smile broadened so far that I thought her face would split. The guy in the bed beside me said he wanted his legs back, and she hurried off to help someone else.

I begin to dress, slowly because my hands are still sore. The legless guy turns his head. “Where you going?” he asks.