In my experience, the most pervasive argument is the last one: it's surprising how often complex applications construct or modify stylesheets on the fly. But like it or not, the XML-based syntax is now an intrinsic feature of the language that has both benefits and drawbacks. It does make the language verbose, but in the end, the number of keystrokes has very little bearing on the ease or difficulty of solving particular transformation problems.

In XSLT 2.0, the long-windedness of the language has been reduced considerably by increasing the expressiveness of the non-XML part of the syntax, namely XPath expressions. Many computations that required five lines of XSLT code in 1.0 can now be expressed in a single XPath expression. Two constructs in particular led to this simplification: the conditional expression (

if..then..else

) in XPath 2.0; and the ability to define a function in XSLT (using

) that can be called directly from an XPath expression. To take the example discussed earlier, if you replace the template

f

f

by a user-written function

by a user-written function

f

f

, you can replace the five lines in the example with:

, you can replace the five lines in the example with:

The decision to base the XSLT syntax on XML has proved its worth in several ways that I would not have predicted in advance:

- It has proved very easy to extend the syntax. Adding new elements and attributes is trivial; there is no risk of introducing parsing difficulties when doing so, and it is easy to manage backwards compatibility. (In contrast, extending XQuery's non-XML syntax without introducing parsing ambiguities is a highly delicate operation.)

- The separation of XML parsing from XSLT processing leads to good error reporting and recovery in the compiler. It makes it much easier to report the location of an error with precision and to report many errors in one run of the compiler. This leads to a faster development cycle.

- It makes it easier to maintain stylistic consistency between different constructs in the language. The discipline of defining the language through elements and attributes creates a constrained vocabulary with which the language designers must work, and these constraints impose a certain consistency of design.

No Side Effects

The idea that XSL should be a declarative language free of side effects appears repeatedly in the early statements about the goals and design principles of the language, but no one ever seems to explain

why

: what would be the user benefit?

A function or procedure in a programming language is said to have side effects if it makes changes to its environment; for example, if it can update a global variable that another function or procedure can read, or if it can write messages to a log file, or prompt the user. If functions have side effects, it becomes important to call them the right number of times and in the correct order. Functions that have no side effects (sometimes called pure functions) can be called any number of times and in any order. It doesn't matter how many times you evaluate the area of a triangle, you will always get the same answer; but if the function to calculate the area has a side effect such as changing the size of the triangle, or if you don't know whether it has side effects or not, then it becomes important to call it once only.

I expand further on this concept in the section on Computational Stylesheets in Chapter 17, page 985.

It is possible to find hints at the reason why this was considered desirable in the statements that the language should be equally suitable for batch or interactive use, and that it should be capable of

progressive rendering

. There is a concern that when you download a large XML document, you won't be able to see anything on your screen until the last byte has been received from the server. Equally, if a small change were made to the XML document, it would be nice to be able to determine the change needed to the screen display, without recalculating the whole thing from scratch. If a language has side effects, then the order of execution of the statements in the language has to be defined, or the final result becomes unpredictable. Without side effects, the statements can be executed in any order, which means it is possible, in principle, to process the parts of a stylesheet selectively and independently.

What it means in practice to be free of side effects is that you cannot update the value of a variable. This restriction is something many users find very frustrating at first, and a big price to pay for these rather remote benefits. But as you get the feel of the language and learn to think about using it the way it was designed to be used, rather than the way you are familiar with from other languages, you will find you stop thinking about this as a restriction. In fact, one of the benefits is that it eliminates a whole class of bugs from your code. I shall come back to this subject in Chapter 17, where I outline some of the common design patterns for XSLT stylesheets and, in particular, describe how to use recursive code to handle situations where in the past you would probably have used updateable variables to keep track of the current state.

Rule-Based

The dominant feature of a typical XSLT stylesheet is that it consists of a set of template rules, each of which describes how a particular element type or other construct should be processed. The rules are not arranged in any particular order; they don't have to match the order of the input or the order of the output, and in fact there are very few clues as to what ordering or nesting of elements the stylesheet author expects to encounter in the source document. It is this that makes XSLT a declarative language, because you specify what output should be produced when particular patterns occur in the input, as distinct from a procedural program where you have to say what tasks to perform in what order.

This rule-based structure is very like CSS, but with the major difference that both the patterns (the description of which nodes a rule applies to), and the actions (the description of what happens when the rule is matched) are much richer in functionality.

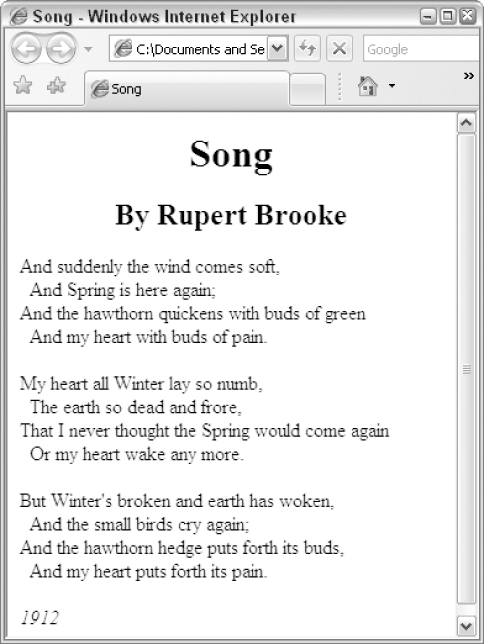

Example: Displaying a Poem

Let's see how we can use the rule-based approach to format a poem. Again, we haven't introduced all the concepts yet, and so I won't try to explain every detail of how this works, but it's useful to see what the template rules actually look like in practice.

Input

Let's take this poem as our XML source. The source file is called

poem.xml

, and the stylesheet is

poem.xsl

.

Rupert Brooke

1912

Song

And suddenly the wind comes soft,

And Spring is here again;

And the hawthorn quickens with buds of green

And my heart with buds of pain.

My heart all Winter lay so numb,

The earth so dead and frore,

That I never thought the Spring would come again

Or my heart wake any more.

But Winter's broken and earth has woken,

And the small birds cry again;

And the hawthorn hedge puts forth its buds,

And my heart puts forth its pain.

Output

Let's write a stylesheet such that this document appears in the browser, as shown in

Figure 1-8

.

Stylesheet

It starts with the standard header.

xmlns:xsl=“http://www.w3.org/1999/XSL/Transform”

version=“1.0”>

Now we write one template rule for each element type in the source document. The rule for the

element creates the skeleton of the HTML output, defining the ordering of the elements in the output (which doesn't have to be the same as the input order). The

instruction inserts the value of the selected element at this point in the output. The

instructions cause the selected child elements to be processed, each using its own template rule.

<xsl:value-of select=“title”/>

In XSLT 2.0 we could replace the four

instructions with one, written as follows:

This takes advantage of the fact that the type system for the language now supports ordered sequences. The

,

,

operator performs list concatenation and is used here to form a list containing the

operator performs list concatenation and is used here to form a list containing the

<br/></span>,<br/><span><author><br/></span>,<br/><span><stanza><br/></span>, and<br/><span><date><br/></span>elements in that order. Note that this includes all the<br/><span><stanza><br/></span>elements, so in general this will be a sequence containing more than four items.<br/></p><p>The template rules for the<br/><span><title><br/></span>,<br/><span><author><br/></span>, and<br/><span><date><br/></span>elements are very simple; they take the content of the element (denoted by<br/><span><img src="/files/04/27/65/f042765/public/lgray.gif" />select = “.”<br/><img src="/files/04/27/65/f042765/public/ggray.gif" /></span>), and surround it within appropriate HTML tags to define its display style.<br/></p><div><p><span><xsl:template match=“title”><br/></span></p><p><span> <div align=“center”><br/></span></p><p><span> <b><xsl:value-of select=“.”/></b><br/></span></p><p><span> </div><br/></span></p><p><span></xsl:template><br/></span></p><p><span><xsl:template match=“author”><br/></span></p><p><span> <div align=“center”><br/></span></p><p><span> <b>By <xsl:value-of select=“.”/></b><br/></span></p><p><span> </div><br/></span></p><p><span></xsl:template><br/></span></p><p><span><xsl:template match=“date”><br/></span></p><p><span> <p><i><xsl:value-of select=“.”/></i></p><br/></span></p><p><span></xsl:template><br/></span></p></div><p>The template rule for the<br/><span><stanza><br/></span>element puts each stanza into an HTML paragraph, and then invokes processing of the lines within the stanza, as defined by the template rule for lines:<br/></p><div><p><span><xsl:template match=“stanza”><br/></span></p><p><span> <p><xsl:apply-templates select=“line”/></p><br/></span></p><p><span></xsl:template><br/></span></p></div><p>The rule for<br/><span><line><br/></span>elements is a little more complex: if the position of the line within the stanza is an even number, it precedes the line with two non-breaking-space characters (<br/><span> <br/></span>). The<br/><span><xsl:if><br/></span>instruction tests a boolean condition, which in this case calls the<br/><span>position()<br/></span>function to determine the relative position of the current line. It then outputs the contents of the line, followed by an empty HTML<br/><span><br><br/></span>element to end the line.<br/></p><div><p><span><xsl:template match=“line”><br/></span></p><p><span> <xsl:if test=“position() mod 2 = 0”> </xsl:if><br/></span></p><p><span> <xsl:value-of select=“.”/><br/><br/></span></p><p><span></xsl:template><br/></span></p></div><p>And to finish off, we close the<br/><span><xsl:stylesheet><br/></span>element:<br/></p><div><p><span></xsl:stylesheet><br/></span></p></div></div></div> </div>

<div class="col-xs-12 text-left pagination-container">

<ul class="pagination"><li class="prev"><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-13" data-page="12">«</a></li>

<li class="first"><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online" data-page="0">1</a></li>

<li class="disabled"><span>...</span></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-5" data-page="4">5</a></li>

<li class="disabled"><span>...</span></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-9" data-page="8">9</a></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-10" data-page="9">10</a></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-11" data-page="10">11</a></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-12" data-page="11">12</a></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-13" data-page="12">13</a></li>

<li class="active"><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-14" data-page="13">14</a></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-15" data-page="14">15</a></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-16" data-page="15">16</a></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-17" data-page="16">17</a></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-18" data-page="17">18</a></li>

<li class="disabled"><span>...</span></li>

<li><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-460" data-page="459">460</a></li>

<li class="disabled"><span>...</span></li>

<li class="last"><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-901" data-page="900">901</a></li>

<li class="next"><a href="/english-books/full-book-xslt-20-and-xpath-20-programmers-reference-4th-edition-read-online-chapter-15" data-page="14">»</a></li></ul> </div>

<div class=""><div class="col-xs-12"><h2>Other books</h2></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-run-to-love-triple-r-book-1-read-online">Run to Love (Triple R Book 1)</a> by <span>Dixon,Jules</span></div></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-knights-legacy-read-online">Knight's Legacy</a> by <span>Trenae Sumter</span></div></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-moxy-maxwell-does-not-love-practicing-the-piano-but-she-does-love-being-in-recitals-read-online">Moxy Maxwell Does Not Love Practicing the Piano (But She Does Love Being in Recitals)</a> by <span>Peggy Gifford</span></div></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-not-second-best-read-online">Not Second Best</a> by <span>Christa Maurice</span></div></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-spell-check-84306-read-online">Spell Check</a> by <span>Ariella Moon</span></div></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-an-instance-of-the-fingerpost-read-online">An Instance of the Fingerpost</a> by <span>Iain Pears</span></div></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-angels-flight-134013-read-online">Angel's Flight</a> by <span>Waldron, Juliet</span></div></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-overdosed-america-read-online">Overdosed America</a> by <span>John Abramson</span></div></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-traitors-blood-civil-war-chronicles-read-online">Traitor's Blood (Civil War Chronicles)</a> by <span>Michael Arnold</span></div></div><div class="list-b-item col-xs-12 col-md-6"><svg enable-background="new 0 0 512 512" viewBox="0 0 512 512" xmlns="http://www.w3.org/2000/svg">

<g>

<path d="m419.17 410.104v62.4h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-19.4c0-11.87 9.63-21.5 21.5-21.5z" fill="#d9ecfd"/>

<path d="m419.17 441.304v31.2h-288.17c-11.87 0-21.5-9.63-21.5-21.5v-9.7z" fill="#c5e2ff"/>

<path d="m132.68 378.104v-370.604h-20.18c-19.33 0-35 15.67-35 35v389.104c0-29.645 24.103-53.64 53.748-53.506z" fill="#db3915"/>

<path d="m132.68 7.5h301.82v370.604h-301.82z" fill="#fc5a36"/><path d="m131 378.104c-29.547 0-53.5 23.953-53.5 53.5v19.396c0 29.547 23.953 53.5 53.5 53.5h303.5v-32h-303.5c-11.874 0-21.5-9.626-21.5-21.5v-19.396c0-11.874 9.626-21.5 21.5-21.5h303.5v-32z" fill="#a42b0f"/>

<path d="m193.467 63.104h180.382v80.72h-180.382z" fill="#ffc85e"/>

<g>

<path d="m434.5 0h-322c-23.435 0-42.5 19.059-42.5 42.485v408.515c0 33.635 27.364 61 61 61h303.5c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-32c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-7.83v-47.396h7.83c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-402.604c0-4.142-3.358-7.5-7.5-7.5zm-349.5 42.485c0-15.155 12.337-27.485 27.5-27.485h12.68v263.534c0 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5s7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-263.534h286.82v355.604h-286.82v-59.38c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5s-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v59.664c-15.988 1.521-30.186 9.242-40.18 20.721zm326.67 391.319h-53.67c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h53.67v16.196h-280.67c-9.167 0-14.875-7.396-14-16.196h208.31c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-208.31c-.875-9.45 4.831-16.2 14-16.2h280.67zm15.33-31.2h-296c-15.99 0-29 13.009-29 29v19.396c0 15.991 13.01 29 29 29h296v17h-296c-25.364 0-46-20.636-46-46v-19.396c0-25.364 20.636-46 46-46h296z"/><path d="m193.469 151.324h180.38c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5v-80.72c0-4.142-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-45.349c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h37.85v65.72h-165.38v-65.72h94.84c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5h-102.34c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5v80.72c-.001 4.142 3.357 7.5 7.499 7.5z"/>

<path d="m341.658 241.592h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/><path d="m341.658 277.409h-116c-4.143 0-7.5 3.358-7.5 7.5s3.357 7.5 7.5 7.5h116c4.143 0 7.5-3.358 7.5-7.5s-3.357-7.5-7.5-7.5z"/>

</g>

</g>

</svg><div><a href="/english-books/full-book-straight-man-read-online">Straight Man</a> by <span>Richard Russo</span></div></div></div>

<!--er-->

</div>

</div>

<div class="row" style="margin-top: 15px;">

</div>

</div>

</div>

<footer class="footer">

<div class="container">

<p class="pull-left">

© FullEnglishBooks 2015 - 2025 Contact for me fullenglishbooks.com@aol.com </p>

<p class="pull-right">

<!--LiveInternet counter-->

<script type="text/javascript">

document.write("<a href='//www.liveinternet.ru/click' "+

"target=_blank><img src='//counter.yadro.ru/hit?t50.6;r"+

escape(document.referrer)+((typeof(screen)=="undefined")?"":

";s"+screen.width+"*"+screen.height+"*"+(screen.colorDepth?

screen.colorDepth:screen.pixelDepth))+";u"+escape(document.URL)+

";h"+escape(document.title.substring(0,150))+";"+Math.random()+

"' alt='' title='LiveInternet' "+

"border='0' width='31' height='31'><\/a>")

</script>

<!--/LiveInternet-->

</p>

</div>

</footer>

<script src="/assets/ba91f165/jquery.js?v=1529425591"></script>

<script src="/assets/618ab67e/yii.js?v=1529414259"></script>

<script src="/js/site.js?v=1722099411"></script>

<script src="/assets/5e1636ad/js/bootstrap.js?v=1529424553"></script>

</body>

</html>

f

f by a user-written function

by a user-written function f

f , you can replace the five lines in the example with:

, you can replace the five lines in the example with: ,

, operator performs list concatenation and is used here to form a list containing the

operator performs list concatenation and is used here to form a list containing the