XSLT 2.0 and XPath 2.0 Programmer's Reference, 4th Edition (71 page)

Read XSLT 2.0 and XPath 2.0 Programmer's Reference, 4th Edition Online

Authors: Michael Kay

The penalty of choosing a real schema for our example is that we have to live with its complications. As we saw earlier, the

“(schema-element(xsl:instruction)|schema-element(xsl:variable))[@saxon:*]”>

A detailed explanation of the syntax used by this match pattern can be found in Chapter 12.

So, to sum up this section, substitution groups are not only a very convenient mechanism for referring to a number of elements that can be substituted for each other in the schema, but they can also provide a handy way of referring to a group of elements in XSLT match patterns. But until XML Schema 1.1 comes along they do have one limitation, which is that elements can only belong directly to one substitution group (or to put it another way, substitution groups must be properly nested; they cannot overlap).

At this point I will finish the lightning tour of XML Schema. The rest of the chapter builds on this understanding to show how the types defined in an XML Schema can be used in a stylesheet.

Declaring Types in XSLT

As we saw in Chapter 3, XSLT 2.0 allows you to define the type of a variable. Similarly, when you write functions or templates, you can declare the type of each parameter, and also the type of the returned value.

Here is an example of a function that takes a string as its parameter and returns an integer as its result:

string-length(lower-case($in))))”/>

And here's a named template that expects either an element node or nothing as its parameter, and returns either a text node or nothing as its result:

You don't have to include type declarations in the stylesheet: If you leave out the as

as attribute, then as with XSLT 1.0, any type of value will be accepted. However, I think it's a good software engineering practice always to declare the types as precisely as you can. The type declarations serve two purposes:

attribute, then as with XSLT 1.0, any type of value will be accepted. However, I think it's a good software engineering practice always to declare the types as precisely as you can. The type declarations serve two purposes:

- The XSLT processor has extra information about the permitted values of the variables or parameters, and it can use this information to generate more efficient code.

- The processor will check (at compile time, and if necessary at runtime) that the values supplied for a variable or parameter match the declared types, and will report an error if not. This can detect many errors in your code, errors that might otherwise have led to the stylesheet producing incorrect output. As a general rule, the sooner an error is detected, the easier it is to find the cause and correct it, so defining types in this way leads to faster debugging. I have heard stories of users upgrading their stylesheets from XSLT 1.0 to XSLT 2.0 and finding that the extra type checking revealed errors that had been causing the stylesheet to produce incorrect output which no one had ever noticed.

These type declarations are written using the as

as attribute of elements such as

attribute of elements such as as

as attribute, because many of the types you can declare (including those in the two examples above) are built-in types, rather than types that need to be defined in your schema. For example, if a function parameter is required to be an integer, you can declare it like this:

attribute, because many of the types you can declare (including those in the two examples above) are built-in types, rather than types that need to be defined in your schema. For example, if a function parameter is required to be an integer, you can declare it like this:

which will work whether or not your XSLT processor is schema-aware, and whether or not your source documents are validated using an XML Schema.

The rules for what you can write in the as

as attribute are defined in XPath 2.0, not in XSLT itself. The construct that appears here is called a

attribute are defined in XPath 2.0, not in XSLT itself. The construct that appears here is called a

sequence type descriptor

, and it is explained in detail in Chapter 11. Here are some examples of sequence type descriptors that you can use with any XSLT processor, whether or not it is schema-aware:

| Construct | Meaning |

| xs:integer | An atomic value labeled as an integer |

| xs:integer * | A sequence of zero or more integers |

| xs:string ? | Either a string, or an empty sequence |

| xs:date | A date |

| xs:anyAtomicType | An atomic value of any type (for example integer, string, and so on) |

| node() | Any node in a tree |

| node() * | Any sequence of zero or more nodes, of any kind |

| element() | Any element node |

| attribute() + | Any sequence of one or more attribute nodes |

| document-node() | Any document node |

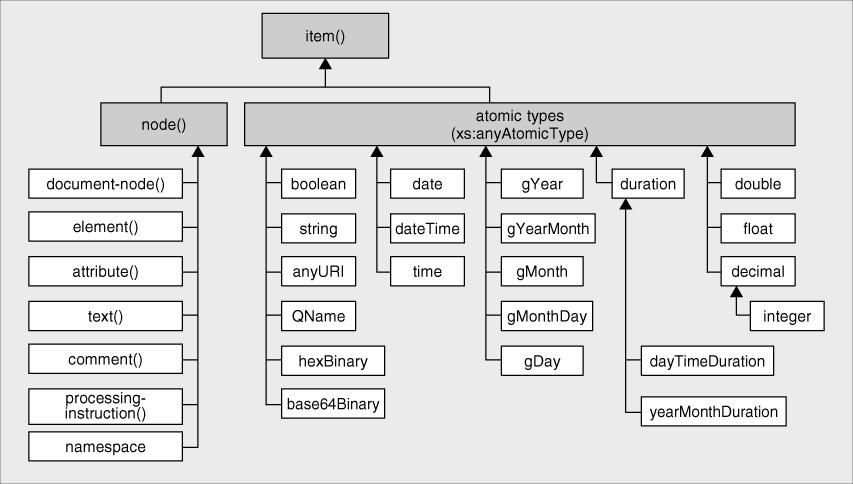

The types that are available in a basic XSLT processor are shown in

Figure 4-1

, which also shows where they appear in the type hierarchy: