Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (14 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

Fellini's Satyricon. Must be about the tenth time I've watched this inspired,

inspiring film. You want to hold on to image after image, treasuring each

one like a painting. The two men collapsing in a ploughed field with a

smoky dawn rising. A human carcass on a crucifix with a vulture flapping on

it. A giant stone head being trundled through the streets. His re-creation of

another age is totally convincing, in an impressionistic way. People behave

differently: kiss by pecking, chew food with an unfamiliar rhythm, stare

at you through heavily made-up, stoned eyes. A sense of decadence in

the colours he uses: the colours of illness, milky blues and yellows, watery

greens and purples, the colour of runny eggs, of mould.

Everything we want for Tartuffe and Richard III is here in this grotesque

world. Fellini uses real freaks and cripples with no moral qualms at all,

so there's lots of useful material for me. A cripple - the sequence where

they kidnap the hermaphrodite - is a bundle of clothes on crutches, knees

bending the wrong way round, like a bird's. No single bit of the body

seems connected to any other bit, a looseness, so that if you undid the

ragged clothes the whole thing would tumble apart.

The ferryman, in the sequence where the hero screws the Earth Mother.

Like my foetus idea: half formed features, damp strands of hair, no

eyebrows, lazy eyes. A bit like Brando. He kills someone and does it

almost gently, without anger or emotion, but like an animal holding on

until the prey stops struggling.

Urgent message to ring Harold Pinter. I have to steady myself. With him,

I tend to go hurtling backwards over the years, deflating like a balloon, until

I'm a sixteen-year-old schoolboy taking those blue Methuen Playscripts to

Esther's Elocution classes. The photos of Pinter on the back always seem

slightly blurred (as if he was hurrying past the camera), adding to his

mystique.

I dial. It rings. Is answered.

`Harold?' A terrifying silence. (If I was tasteless, I would write `a

menacing pause'.) I lean into the phone nervously: `Harold?'

`Yes?' Stern, guarded. Clearly no one he knows addresses him as

Harold.

`Hello . . .' My voice growing thinner and squeakier by the moment,

`yes, uhm, it's Tony Sher, I have a message -'

Instant warmth. 'Tony, hello, how good of you to ring hack, how arc

you;,

Ile's directing a new Simon Gray play and wants me to do it. 'I've

spoken to your agents but there seems to be some uncertainty. Are you

staying with the R S C

'Well, yes, I think I am, I think I'm going to do Richard the Third, I

mean, I am, yes, I am. Definitely.'

'Richard the Third, Isn't that funny, I was just saying to Simon Gray

this morning that he's hound to he going hack to Stratford to do a Richard

the Third.'

'I know, it's terribly predictable.'

He laughs. 'What a pity. The part in Simon's play is wonderful.'

'Oh dear. Don't tell me.'

'Still, so is Richard the Third I suppose.'

Ile wishes me well, says he'll come up and see it and makes me promise

not to stay with the R S C forever.

Put down the phone and it rings again immediately. Howard Davies.

lie says Mal has read The Party and is willing to play either part, but that

he (Howard) can't really see it the other way round. Also he doesn't see

why Mal should always lose out in casting because of his generosity. I

heartily agree, thank him for his honesty and wish him good luck with the

production.

So it's still just Richard 111. Slight temptation to read the Simon Gray

play ...

BBC STUDIOS, WHITE CITY Recording TartuJJe.

I'm not needed on the first day, but pop in for a make-up test. Find

they're moving so fast they might get to me by the evening. The make-up

stays on, my costume is hurriedly found, and before I know it I'm on the

studio floor doing my first scene. Rather like someone popping into

hospital to have a corn removed and finding themselves undergoing major

heart surgery.

The atmosphere in the studio is tense and rushed, everyone working

against the clock - television's disease. First takes are being accepted far

too easily. At the end of the day Bill looks like a ghost. It was his first time

ever in a studio. Says it was one of the scariest days of his life, and rather

like those disaster movies where the stewardess finds herself flying the

plane.

But Bill and Tom Kingdon, the technical director, find their feet quickly

over the next few days and it all becomes much better paced.

`Top of the Pops' being recorded in the next studio. I go out into the

assembly area where the groups are lounging about. I am dressed in full

Tartuffe gear, long black wig, black smock, stockings, but don't look at

all incongruous. I could be the lead guitarist from any one of these bands.

Complete chaos on Friday. Nigel Hawthorne is suddenly summoned

to accept an award for `Yes Minister' from Mary Whitehouse's Viewers

Association. It's to be presented by Margaret Thatcher, who has written

a sketch(?!) which she is going to perform (?!!) with Nigel and Paul

Eddington. So, Nigel heads off to help launch Thatcher's new career

while, back in the studio, schedules are frantically re-arranged. I end up

working non-stop from I o.oo a.m. to I o.oo p.m. with lunch and tea breaks

being used for make-up changes. Spend all day in a state of suppressed

fury that this has been caused by a publicity stunt for Mary Whitehouse,

who ranks high on my list of major irritants, alongside queuing in banks

and can-openers not working.

Nigel returns and we do our main scene in two takes, both excellent,

both very different and inventive, trusting where the other leads.

In the evening much merriment over the bum scene (which might cause

Nigel's next meeting with Mary Whitehouse to be in the Number One

Court at the Old Bailey when she digs up some ancient law - Aiding and

Abetting the Airing of an Arsehole?). In the make-up room all the actors

are sitting in their chairs being made up, while I have to kneel on mine

pointing in the other direction. In the studio it gets quite embarrassing.

Whereas in the theatre the whole scene just flits by (trousers down,

trousers up, before you know it), in the studio they keep calling a halt and

I'm left stranded on the table, exposed bum in the air, while technicians

stroll around whistling, adjusting lights and camera angles. The make-up

girl dashes in to touch-up the false tan on my nether cheeks. As she's

bent over her task, I happen to burp violently.

`Oh, that's very nice,' she says.

`You're lucky it didn't come out the other end.'

`I dunno. I've always wanted a parting in my hair.'

I glimpse one of the scenes being played back on a monitor. I'm no longer

sure I have successfully scaled down my performance. I thought I was

going from the theatrical to the televisual, but might have taken a wrong

turning and ended up with the operatic.

On the last evening we finish with time to spare so they decide to do

re-takes on the much over-exposed bum scene. Back to kneeling in the

make-up room and then on to the table in the studio. During the take

Nigel starts corpsing and the scene grinds to a halt. He says, `This isn't

like me at all. I'll be all right now.' Again we try and again he corpses. Ali

and I take a sadistic delight in this, having disgraced ourselves so often in

the theatre. Eventually they have to compromise on a different angle and

actually remove Nigel from the studio. He is led away, still protesting,

`But it isn't like me at all, I promise you.'

BARBICAN Press conference. In this morning's Guardian, Nicholas de

Jongh has somehow got hold of all the information about next season and

leaks it, making today's conference somewhat pointless.

Waiting to go in, I meet Ken Branagh for the first time. We share a

common problem - living in the shadow of Olivier's films, Henry V and

Richard X. Because they're on film, they have entered this century's

consciousness in a way that is quite daunting for any actor or director

approaching the plays. However much people might glory in the memory

of Gielgud's or Warner's Hamlet they are not there to be hired from the

local video shop. Branagh says when he was at school he used to do an

impersonation of Olivier's Richard without even knowing what it was. He

says, `Olivier's performances are there, indelibly. We might as well put

them to one side and just get on with the job.' Which makes me feel much

better.

De Jongh has the gall to show up for the press conference. So Terry

begins, `For those of you who haven't read this morning's Guardian, let

me outline our plans ...' He says this glancing in de Jongh's direction

and smiling politely. Quite deadly. Also throws a few well chosen barbs

in the direction of Michael Ratcliffe who has just taken over as the Observer

critic and has been R S C-bashing in his first columns. Much turning of

heads over in the thespian corner to identify this new critic. It's difficult

getting to know what they look like since their natural habitat is nocturnal

- the dark of the auditorium.

Terry is a magnificent speaker - a gift for fluency without referring to

notes, never drying or stumbling. It's rumoured that politics was his second

choice of career.

When it comes to question time, there's an embarrassed silence from the

assembled journalists. Terry encourages them to ask the actors questions. Nothing. Over in our corner, the director John Caird whispers, `Mister

Sher, will you be playing the part in a hump?' and Roger Rees adds, `And

will it be a hump from stock or a spanking new one?'

Things are grinding to a halt. Terry politely requests that they all lay

off jokes about how difficult the Barbican is to find, it's been done to

death and now is a good time to stop. This topic seems to animate the

journalists more than anything else.

One says supportively, `In a recent survey it was proved that eighty-four

per cent now find it easy to find.'

`Eighty-four per cent of what?' asks the playwright David Edgar.

`Of people who find it.'

`How can they ask the people who don't find it?'

`They don't. The other sixteen per cent do eventually find it, but found

it difficult to find.'

A moment later a very harassed Steve Grant (from Time Out) bursts in

clutching briefcase and coat. Takes his place looking puffed and bewildered, and begins leafing through the publicity handout.

`Clearly one of the sixteen per cent,' whispers David Edgar.

My day always starts with scanning the TV listings and setting the video

recorder. If you have long enough you can research any part without

moving from your living-room.

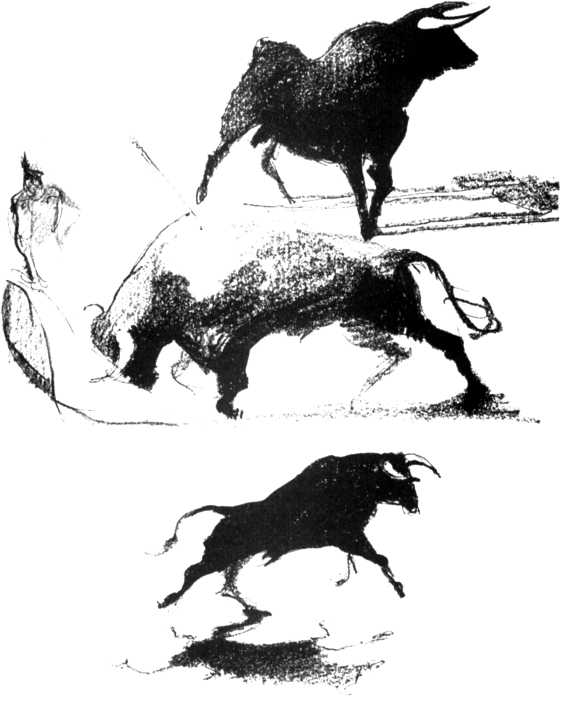

`The World About Us' on matadors. When I go to Spain, I find the

bullfight compulsive viewing. Dangerous theatre. Watching the fighting

bulls today, I realise they have many of the qualities that I've been thinking

about for Richard. Sketching them is a similar sensation to sketching

Lion's Head; the folds are silky smooth but inside there is a rock-hard

power. Like sharks, they have the appearance of a `nightmare creature' -

something to do with their blackness even in bright sunshine; you can

hardly make out their eyes or mouth; the head is a black stump; the white

horns always defined against the black. Look at the head closely and it

has a primeval, reptilian quality; heavily wrinkled, a stupid brutal face,

slightly sad. Ronnie Kray.

When they first burst into the ring there is great agility, they spring,

change direction, like they're dancing. The massive hump - this, of course,

is most relevant to me - is full and hard, a pack of muscle. Later, pierced

like a pin-cushion, it deflates. The blood is a crude orange splash bubbling

down their flanks, like someone's thrown paint at them. When they charge, their muscles seem to dilate, their size doubles, their weight doubles -

the nightmare creature thunders forwards.