Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (2 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

The Swan Theatre didn't even exist in 1984 - it was still our rehearsal

room then, the Conference Hall often mentioned in this book - but it is now

the best auditorium I know, both as performer and audience member. It

creates the illusion, essential for a good classical space, of functioning

like a camera: switching from close-up to wide shot, from intimate to

epic. It's where I've done all my recent work with the RSC, and I always

feel intense excitement when I arrive there to open a new show, and then

intense sadness when it closes. So at last Saturday night's performance

of Othello I was already rather emotional when Keith suddenly presented

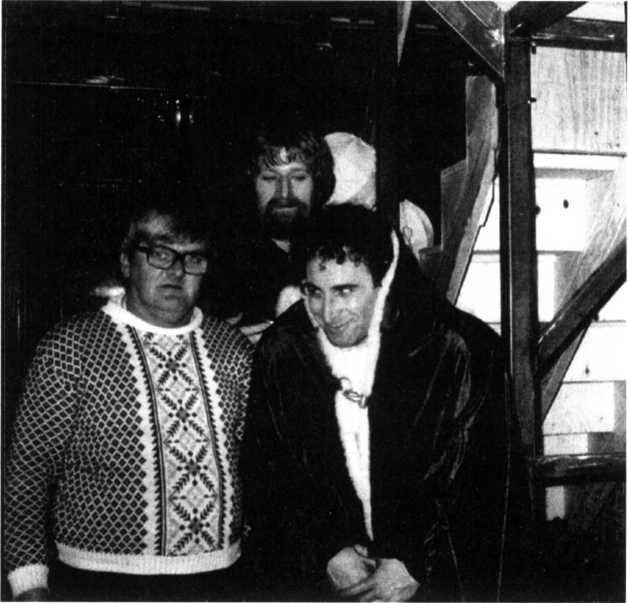

me with the photograph of backstage life during Richard III.

Looking at it, I remembered that for all the struggle and doubt of

the journey, and for all my inadequacy at verse-speaking, the role of the

`bottled spider' turned out so well for me that it's been quite a hard act

to follow. (Who was it that said, Be careful of getting what you want'?)

I also remembered that one of the other men with me in the photo,

Black Mac, is no longer with us - he died in 2001 - and I miss him. As I

hope this hook reveals, he was a tremendous, larger-than-life character:

originally from the North-East, working both as an army sergeant and

a theatre dresser, rude, funny, kind, aggressive, full of contradictions,

the sort of character Shakespeare would've loved. I like it when, in the diary entry dated 18 June, the day before our opening, Mac overhears

me practising my speeches and says: `Clever, henny, clever, must be clever

to remember that fokkin bollocks.' But then later he confides in me: `The

shows I've seen here, mate, the memories I've got, and I've viewed them

from angles no other bugger has ever seen, no fokkin critic, not even the

directors have seen them like I have, from my special places in the wings.'

So it is with Black Mac in mind - and other departed figures who

haunt the pages of this book, like Dad, and indeed Olivier - that I now

invite the reader to go on a twenty-year-old journey with me, in search of

one of Shakespeare's most dynamic and original creations, King Richard

III.

Antony Sher, London

August 1983

Summer.

To be more precise, my thirty-fourth summer in all, my fifteenth in

England away from my native South Africa, my eleventh as a professional

actor, and my second as a member of the Royal Shakespeare Company.

These last two years have been eventful, a time of change. Last year, a

successful season in Stratford playing the Fool in King Lear and the title

role in the Bulgakov play Moliere. Then, in November, an accident. In the

middle of a performance as the Fool one of my Achilles tendons snapped

and I suddenly found myself off work for a period that was to last six

months.

Unexpectedly, this proved to be a happy time. Apart from anything else,

the enforced rest was a chance at last to do all those paintings and sketches

I'd long been planning. With my leg encased in plaster I'd sit for hours

at my easel, just managing now and then to hobble a few steps back to

get a better view. If anything, time passed too quickly. After years in a

profession where you're on public display, it was a relief to be a recluse

for a change. My temporary disability made any journey from my home

in Islington difficult and vaguely humiliating, so few were worth it. There

was one exception.

The Remedial Dance Clinic in Harley Street is so-called because it

serves as repair shop to most of the dance companies. Each day I would

have to make my way there for long sessions of physiotherapy. This

was a new experience for me. Strange, invisible currents of electricity,

ultra-sound and deep-heat were passed into my leg and somehow started

it working again. The process was slow. When the plaster first came off,

the white shrunken leg revealed underneath was virtually useless. But

gradually, stage by stage, my crutches could be exchanged for a walking stick, then that was abandoned for boots with stacked heels, and eventually

I was walking again in ordinary shoes. Now the process accelerated in the

other direction. Running, then jumping, even trying a cautious cartwheel

... preparing to go back into King Lear for the London run at the Barbican

Theatre.

Another treatment of a very different sort, which I decided to try while

I had the free time, was psychotherapy. Here the currents are stranger,

but just as impressive. A man called Monty Berman has been listening

patiently to the story of my life, yawning only occasionally. He makes

comments like `Let's validate that', when I relate certain chapters, and

`Bullshit!' to others. I sit there, peering at him through my large, tinted

specs, nodding in agreement, and then hurry away afterwards to check

words like `validate' in the dictionary.

So the Achilles incident has been a kind of turning point. Invisible

mending from head to heel. Now I also pay regular visits to the City Gym,

the Body Control Studio, and various swimming pools. I have developed,

along with new muscles and energy, that brand of smug boastfulness on

the subject of physical fitness: the kind that makes other people - and I

remember this well from being on the other side - want to slap you around

the mouth.

Going back into King Lear after six months away was like climbing on

to the horse after it has thrown you. But its short London run is already

over and I escaped uninjured. I have since opened in a new production of

Tartuffe, playing the title role. This has been directed by Bill Alexander

(as a companion piece to his production about its author, Moliere) and has

been a great hit with audiences, although less so, I believe, with the critics.

My uncertainty stems from the fact that, along with a whole string of

unwanted habits ditched since going to Monty, I have stopped reading

reviews. I never thought I could do it, never thought I could live without

them. But now, apart from the occasional twinge, I hardly miss them at

all. Rather like giving up cigarettes, I suppose. Unfortunately, I still smoke

quite heavily. Which is just as well, as I'm required to do so in the new

David Edgar play, Maydays, which is about to go into rehearsal ...

In the meantime, at the Barbican, Tartuffe and Moliere continue in the

repertoire.

JOE ALLEN'S Dining with a friend one evening, I notice Trevor Nunn

[R S C Joint Artistic Director] at another table. He's been on sabbatical

ever since I joined the R S C last year, so I haven't met him properly. Yet he is the R S C, so a social gesture might be required. Is it just a little nod?

Or a little wave? Or a little of each with a mouthed, `Hi, Trev'? Or as

much as popping over to his table and using the more formal, `Trevor,

hello'? Luckily, his back is to me at the moment, so none of these decisions

will have to be taken till my exit. For the moment I can concentrate on

my Caesar Salad.

Hours later, my companion goes to the loo and almost instantly, as if

by magic, Trevor Nunn is leaning forward on to my table.

`Tony.'

`Trevor!'

`I did enjoy Tartuffe the other evening.'

`Ah. Good. Thank you.'

`I thought Bill Alexander got a perfect balance in the production between

the domestic naturalism and the black farce.'

`Yes, hasn't he? It's a -'

`You really ought to play Richard the Third soon.'

`Oh. Well. That would be nice.'

I look up at him hopefully. He smiles politely, a touch of enigma, and

retreats, disappearing into the smoky, gossipy crowd ...

Back at home, Jim [Jim Hooper, R S C actor] says, `Beware. It's only Joe

Allen's chat.' He's quite right, of course, so I try not to think any further

about it. Which is like trying not to breathe.

There was something unfinished in what he said. `You really ought to

play Richard the Third soon -'what might he have said next? `And I shall

direct it'? Or, `but not for us'? In the next few days these nine words,

this innocent piece of Joe Allen's chat is subjected to the closest possible

scrutiny. It is viewed from every possible angle, upside down and inside

out, thoroughly dissected, at last laid to rest, exhumed, another autopsy,

finally mummified.

I try not to tell people about it, but it does have a peculiar life of its

own, this ghost, and will keep slipping out.

I make the fatal mistake of mentioning it to Mum on one of my Sunday

calls to South Africa. She instantly starts packing.

Another mistake is to mention it to Nigel Hawthorne (playing Orgon)

at the next performance of Tartuffe. He twinkles. From then on the

shows are accompanied by comments like, `Thought I noticed Tartuffe

developing a slight limp this evening', or, overhearing me complaining

about putting on weight, he says, `Can't you just edge it up for the hump?'

This successfully helps to shut me up, so apart from Mum's weekly

question, `And Richard the Third?', as if we were about to open, there is

no further mention made of it.

Time passes. Now it is winter.

BARBICAN Paranoia is rampant these days, down in our warm and busy

warren, miles below a chilly City of London. The end of the season, and

for many their two-year cycle, is in sight. Rumours are rife about world

tours of Cyrano and Much Ado, videos ofMoliere and Peer Gynt. Many are

keen to return to Stratford where, rumour boasts, Adrian Noble will direct

Ian McKellen as Coriolanus and either David Suchet or Alan Howard

will be giving an Othello. But will people be asked back and, if they are,

will good enough parts be on offer? It is widely believed that planning

meetings are already in session in those distant offices above street level.

As the directors pass among us for their lunches, suppers and teas, actors

perform daredevil feats of balance in order to eavesdrop on conversations

half a room away.

I am not above these feelings of unease myself. These years with the

company have been the happiest of my career and I too don't want them

to end.

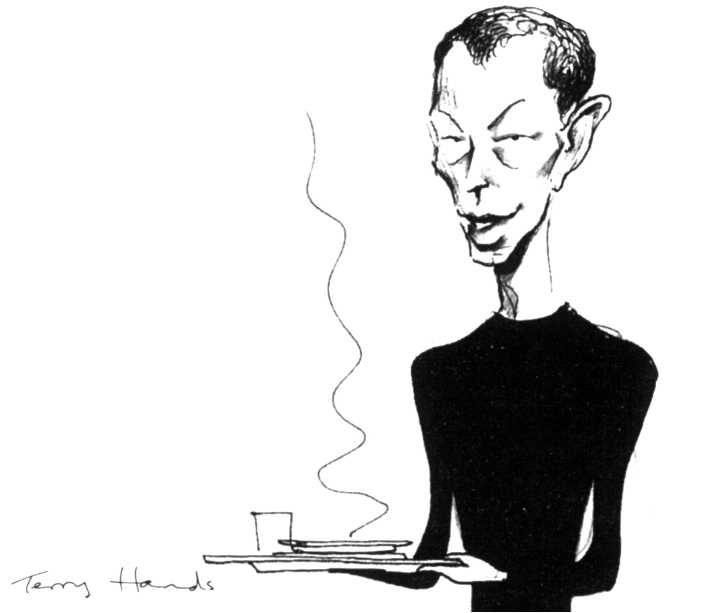

CANTEEN Terry Hands

[R S C Joint Artistic

Director] suddenly at my

elbow in the lunch queue. Is

it because he's re-rehearsing

Poppy at the moment that

he seems even more oriental

than usual? Dressed in

black, smiling slightly and

knowingly from hooded

eyes, a sense of immense

energy and power in repose.

He says, `We really ought to have one of our meals soon.'

`Absolutely. When?'

`Well, I'm busy with Poppy technicals till the week after next. Has Bill

spoken to you?'

`No.'

`Bill hasn't spoken to you?'

`No. What about?'

`Oh, you know ...' He smiles. `Life and Art.'

`Ah. No. Definitely not.'

`We'll let Bill speak to you first.' He starts to go. Actors leaning towards

us at forty-five degree angles quickly straighten, ear erections drooping.

Terry turns back to me and smiles.

`Oh, and don't sign up for anything else next year. Yet.'

Bill Alexander rings. We arrange lunch for Monday.