Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (8 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

A thank-you card from Charlotte Arnold with this PS: `I have started the

ball rolling re Richard III. Should have news in January about homes and

centres for the disabled that we could visit. Did you mean what you said

about crutches? It's just that I've been thinking they might actually be the

safest way of you playing extreme disability. Can't think of anything else

that would take the strain off you in the same way. It's what they're

designed to do. But were you serious?'

FOYLES Finally buy an Arden edition of Richard III, to read in South

Africa. (And leave behind there perhaps?) The cover is very strange -

hollow eye sockets and gaping mouths, all rather vaginal.

BARBICAN CANTEEN Two of the directors, Adrian Noble and Barry

Kyle, have a little light supper at my table before another planning meeting.

Neither say anything about Stratford or the current situation. Instead

Adrian starts talking about aeroplane crashes and the recent case of a

woman suing one of the airlines for shattering her nerves. The plane had

started to plummet and only at the last moment did the pilot regain control

and yank it back up into the air.

`So there are all these people,' Adrian says, munching at his supper,

`who have felt what those last few minutes are like. That fall. Can you

imagine? And who've lived to remember it.' He always discusses matters

like this with a kind of bright-eyed, yet detached, fascination. Perhaps it's

because he's an undertaker's son.

They go off to their planning meeting and I sit viewing Sunday's flight

in a new light.

In this morning's Guardian a full-page advertisement for the Free Nelson

Mandela Campaign. Hundreds of signatures, mine among them. Bad

timing. Hope the South Africans don't go through this with a fine tooth

comb, which of course they will. Image of being frog-marched out of the

airport lounge and shot against the nearest wall.

Howard Davies [RSC director] rings. He's doing the Nicks Wright play

now and says there's a terrific part in it for me.

`What's it about?'

`Well, it's set in Cairo -'

`Oh God. Another Arab.'

`No, no. British Intelligence, Second World War. An officer with a

Napoleonic complex ...'

The play sounds very exciting. It's now scheduled for Slot Four. The

Peter Barnes play is in Slot Five, with Adrian directing, and apparently it

also contains a terrific part for me. `Adrian's been itching to talk to you

all week,' Howard says.

I tell him that Ron had advised me to have a play out after Richard.

`Yes I know. He relayed that conversation to us and I got rather angry.

I said to them, if we want Tony in the season, and we do, what's the point

in having him do as little as possible','

`Well actually Ron made some rather good points about osteopaths'

couches ...'

But this news is too good to start worrying about minor details like

health. Two new plays are a decent compromise. I ring Bill to tell him,

`It all sounds very promising.' He says that he's definitely going to offer

Buckingham to Malcolm Storrv. It will be a powerful image: the small

deformed Richard with this giant as right hand man. And our rapport as

actors and friends will be a corner-stone for the whole production.

Last minute packing, feeling very excited about everything, not least

that now is the winter and on Monday the summer ...

The thing I keep remembering is Monty seeing me to the door after

our session on Tuesday. He suddenly said, `I envy you. I'd love to see

South Africa again. Christ, I can't watch a programme on 'I'V about that

bloody country without crying.'

Sunday r i December

Sitting next to me on the plane is a ten-year-old boy. He looks up and

says with great excitement, `We're going to live in South Africa!' He's

called Leon and is from Manchester. Points across the aisle to where his

parents sit, restraining lap-fulls of his little brothers and sisters. As the

eldest he has volunteered to sit on his own.

As we are about to take off, I offer him the window seat. He says, `Ooo,

could I?' He has never flown before and the take off is intolerably exciting.

In fact he can hardly bear to watch this miracle and keeps turning back

to me blushing and grinning.

Dawn. The round window is a milky blur of pink, orange, blue. Gradually

it focuses into one of these endless fields of clouds.

`Is it ice on the sea?' asks Leon as he wakes and clambers over for a

good peer. He stares in wonderment. `The air must be thin up here, so

close to outer space.'

An hour later the clouds are more mountainous, erupting. They break

dramatically, disappear, and there below is a red land with soft black hills

that look as if they're melting in extreme heat, and one long, white,

perfectly straight road. Africa.

I point it out to Leon who shouts, `It's Africa, it's Africa! Look Dad,

it's Africa!'

The father looks at me wetly and shrugs, apologising for his son. I've

taken a dislike to this man, primarily because he's emigrating to South

Africa.

As we are coming in to land at Jo'burg I say to Leon, `Come on you'd

better move over to the window seat.' He's looking glum and says, `My Dad has said not to bother you anymore.'

`Oh don't be silly.' I turn to the father. `He must see the landing in his

new country. Something for him to remember in years to come,' wondering

if the man perceives any double meaning at all.

Leon presses his face to the window again and remains glued there as

we descend and South Africa turns into reality with a gentle bump from

below.

During the connecting flight to Cape Town I become very emotional.

Different feelings and memories welling up, settling, welling up again. As

the plane begins its descent they start playing schmaltzy music which

makes it all much worse. Bits of me, dormant for years, coming to the

surface. Excitement and fear.

Stepping off the plane, the blast of dry heat, the baking afternoon with

its brilliant blue sky, is all familiar and calming.

Monty and I were both right about the photographers: there aren't any,

yet there is one - my sister Verne clicking away on an Instamatic as I walk

into the airport lounge. Everyone is there, brown and glowing: the men

have taken the afternoon off work. Mum is presiding, looking glamorous

in the simplest of summer frocks and with a film star's instinct for when

the shutter is going to click. My older brother Randall says, `Hi, howzitt?'

as if he saw me yesterday, and hugs me; he's rounder and greyer than I

remember. Dad pops up from behind a group to go `Haah', which is his

shorthand for `Hello and how are you?' Esther, my drama teacher (we

called it `elocution') from way back, flies into my arms, crying. The

nephews and nieces all come up shyly to shake hands and be kissed,

grown into new shapes, new people. Everyone keeps saying, `You look

terrible. Don't they feed you in England? So white, like a ghost.' They

ask about my dreadfully short hair cut (to go under Maydays wigs). I tell

them I'm thinking of catching up with some National Service while I'm

here.

Driving back from the airport, nothing is familiar until Green Point

Common and the Sports Stadium. Memories of walking back with Tony

Fagin from Saturday afternoon bioscope, discussing The Art Of The

Motion Picture. And then more memories as we drive along the beachfront

- certain blocks of flats, the Pavilion, the Aquarium - but distantly,

sensations rather than clear pictures.

The house in Alexander Road is transformed. They've split it down

the middle and sold the other half. It's hardly recognisable, but I find my

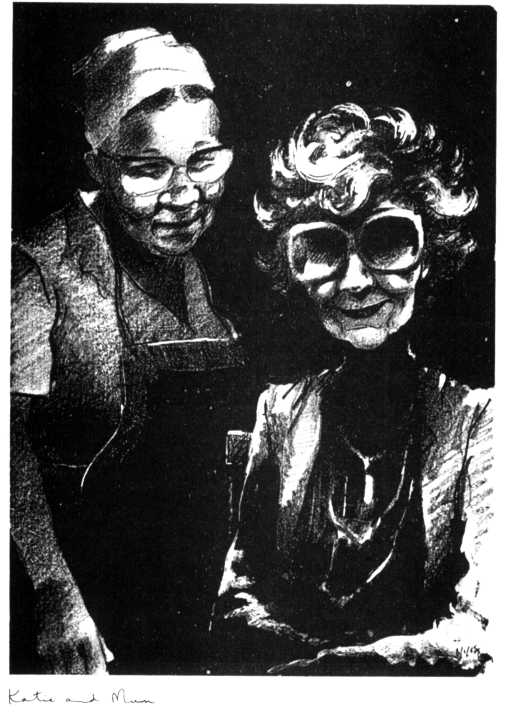

way through to the back yard calling, `Katie, Katie.' She comes out of the maid's room. Still wearing those little aprons and linen caps, but older,

shorter, squatter. Her shy smile showing gold among the white teeth. We

hug. `Oh, Master Antony, oh, Master Antony,' she keeps saying.

The house is like it would be in a dream. A familiar place put together

wrongly. A few things have survived the rebuilding. The stair rail. A

cupboard door. I round a corner and there's a piece I recognise, the rest

strange. Even the smell is quite new. A different furniture polish I suppose.

I'm on display everywhere. Every inch of wall space is covered in photos

of me or my paintings or posters of plays. It makes me feel rather

uncomfortable; as if I've died and this is the shrine.

I'm taken on a grand tour. Mum watches my reactions closely, keeps

asking, `Well, what d'you think?' and I keep replying, `I don't know, it's

very strange.'

Their bedroom. Blinds drawn against the strong afternoon sun which

still saturates the room and makes the blinds glow. Little strips and squares

of sunlight have got through and fall across the bed, and across the soft

pale carpet. A radio plays quietly. This feeling of a hot afternoon indoors,

with the radio a tiny, constant comforting sound - that's the closest feeling

to what it was like being a child here.

Wake to that smell of the sea ... Dad and Katie in the back yard chatting

away in Afrikaans.

Breakfast. Both Mum and Dad have capsules to take with their coffee.

His are thick, black things like slugs. When I ask what they're for, he says,

`Lord alone knows, but if I was ten years younger I'd've had triplets by

now.

Mum's are prettier, little opaque golden baubles. `They are very expensive,' she says, `a natural extract made from the oil of Evening Primrose,

for the skin, for circulation and so much more. Apparently the entire

population of Russia are given these free for one month each year.'

`That's why their Premiers keep dying,' mutters Dad as he heads off

to work.

`Tsk,' goes Mum, and settles down with Katie to plan the day's menus;

there's meat to be taken out of the deep freeze, recipes to be checked

through. That done, she begins her own notes for the day; careful lists

written in her curving elegant handwriting (so familiar from those blue

airmail envelopes that drop through the letter box back in Islington)

concerning shopping and appointments.

Katie starts washing up the breakfast things. She is rather proud of the

batch of bagels she baked for my homecoming.

`Were they all right, Madam?'

`Haven't tasted one yet,' says Mum concentrating on her list.

`But do they look all right?'

`Look fine.'

`I burnt a few for Madam, Madam mos' likes them burnt.'

`Mmm.'

Katie smiles secretly to me, almost winks, as if to say `I keep her happy

and she stays out of my hair'.

Their relationship seems to have mellowed over the years. In my

childhood I remember stormy rows; Katie was always packing and leaving,

often did. One or the other would eventually apologise sulkily, all would

be well again until the next time.

I wonder if either have ever realised the deep affection they have for

one another. They're both in their early sixties now, having spent forty

long years together. They see more of one another than they do of their

husbands, and yet all the time leading very different lives.

Mum's day is made up of her shopping, her beauty treatments, massages,

manicures and pedicures, her classes in keep fit and philosophy, her

spiritualist meetings, her visits to theatre, cinema, ballet, variety shows,

anything to fill the long hours of leisure.

Katie's day begins at five o'clock in the coloured township Bonteheuwel;

she cooks breakfast for her husband, catches the six o'clock bus to Sea

Point, works here from seven till five, back home to make supper and do

the housework there, then to bed at midnight. She says to me, `I thank

God that I've still got my health so I can work hard for Madam and

myself.'

S A U N D E R S BEACH Astonishing to see the beach mixed. Black men in

the briefest swimsuits sunbathing next to Jewish princesses, who lie face

down with bikini-tops discreetly untied. And yet the Immorality Act still

officially exists. So they lie there inches away from one another, very

nearly naked, watching with interest and wariness, sensing, smelling,

stirring one another, but not permitted to touch.

The sea is choppy, the wind strong and cold. As soon as you are

protected from it, baking heat. Clouds tumble over the Seven Apostles. I

notice how magnificent Lion's Head is, as if for the first time. This

ex-volcano dominates Sea Point; our school anthem was called `Beneath the Lion Bold'. The mountain was so familiar that I stopped noticing it,

but seeing it now, it has tremendous power. Richard III is in there

somewhere. But which bit is the head, which the hump?

`Haah.' Dad back from work. He goes into the kitchen to nibble at the

supper Katie is preparing, and to chat in Afrikaans. I think they both look

forward to these moments of their day.

`How was work?' I ask.