Your Inner Fish: A Journey Into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body (28 page)

Read Your Inner Fish: A Journey Into the 3.5-Billion-Year History of the Human Body Online

Authors: Neil Shubin

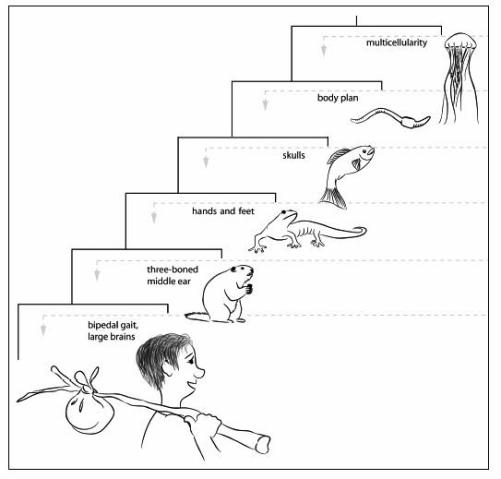

From Chapter 1 through Chapter 10, we have shown that deep similarities exist between creatures living today and those long deceased—ancient worms, living sponges, and various kinds of fish. Now, armed with knowledge of the pattern of descent with modification, we can begin to make sense of it all. Enough fun at the circus and zoo. It’s time to get down to business.

We have seen that inside our bodies are connections to a menagerie of other creatures. Some parts resemble parts of jellyfish, others parts of worms, still others parts of fish. These aren’t haphazard similarities. Some parts of us are seen in every other animal; others are very unique to us. It is deeply beautiful to see that there is an order in all these features. Hundreds of characters from DNA, innumerable anatomical and developmental features—all follow the same logic as the bozos we saw earlier.

Let’s consider some of the features we’ve already talked about in the book and show you how they are ordered.

With every other animal on the planet, we share a body composed of

many cells.

Call this group multicellular life. We share the trait of multicellularity with everything from sponges to placozoans to jellyfish to chimpanzees.

A subset of these multicellular animals have

a body plan like ours,

with a front and a back, a top and a bottom, and a left and a right. Taxonomists call this group Bilateria (meaning “bilaterally symmetrical animals”). It includes every animal from insects to humans.

A subset of multicellular animals that have a body plan like ours, with a front and a back, a top and a bottom, and a left and a right, also have

skulls and backbones.

Call these creatures vertebrates.

A subset of the multicellular animals that have a body plan like ours, with a front and a back, a top and a bottom, and a left and a right, and that have skulls, also have

hands and feet.

Call these vertebrates tetrapods (animals with four limbs).

A subset of the multicellular animals that have a body plan like ours, with a front and a back, a top and a bottom, and a left and a right, that have skulls, and that have hands and feet, also have a

three-boned middle ear.

Call these tetrapods mammals.

A subset of the multicellular animals that have a body plan like ours with a front and a back, a top and a bottom, and a left and a right, that have skulls and backbones, that have hands and feet, and that have a three-boned middle ear, also have

a bipedal gait and enormous brains.

Call these mammals people.

A human family tree, all the way back to jellyfish. It has the same structure as the one for the bozos.

The power of these groupings is seen in the evidence on which they are based. Hundreds of genetic, embryological, and anatomical features support them. This arrangement allows us to look inside ourselves in an important way.

This exercise is almost like peeling an onion, exposing layer after layer of history. First we see features we share with all other mammals. Then, as we look deeper, we find the features we share with fish. Deeper still are those we share with worms. And so on. Recalling the logic of the bozos, this means that we see a pattern of descent with modification deeply etched inside our own bodies. That pattern is reflected in the geological record. The oldest many-celled fossil is over 600 million years old. The earliest fossil with a three-boned middle ear is less than 200 million years old. The oldest fossil with a bipedal gait is around 4 million years old. Are all these facts just coincidence, or do they reflect a law of biology we can see at work around us every day?

Carl Sagan once famously said that looking at the stars is like looking back in time. The stars’ light began the journey to our eyes eons ago, long before our world was formed. I like to think that looking at humans is much like peering at the stars. If you know how to look, our body becomes a time capsule that, when opened, tells of critical moments in the history of our planet and of a distant past in ancient oceans, streams, and forests. Changes in the ancient atmosphere are reflected in the molecules that allow our cells to cooperate to make bodies. The environment of ancient streams shaped the basic anatomy of our limbs. Our color vision and sense of smell has been molded by life in ancient forests and plains. And the list goes on. This history is our inheritance, one that affects our lives today and will do so in the future.

WHY HISTORY MAKES US SICK

My knee was swollen to the size a grapefruit, and one of my colleagues from the surgery department was twisting and bending it to determine whether I had strained or ripped one of the ligaments or cartilage pads inside. This, and the MRI scan that followed, revealed a torn meniscus, the probable result of twenty-five years spent carrying a backpack over rocks, boulders, and scree in the field. Hurt your knee and you will almost certainly injure one or more of three structures: the medial meniscus, the medial collateral ligament, or the anterior cruciate ligament. So regular are injuries to these three parts of your knee that these three structures are known among doctors as the “Unhappy Triad.” They are clear evidence of the pitfalls of having an inner fish. Fish do not walk on two legs.

Our humanity comes at a cost. For the exceptional combination of things we do—talk, think, grasp, and walk on two legs—we pay a price. This is an inevitable result of the tree of life inside us.

Imagine trying to jerry-rig a Volkswagen Beetle to travel at speeds of 150 miles per hour. In 1933, Adolf Hitler commissioned Dr. Ferdinand Porsche to develop a cheap car that could get 40 miles per gallon of gas and provide a reliable form of transportation for the average German family. The result was the VW Beetle. This history, Hitler’s plan, places constraints on the ways we can modify the Beetle today; the engineering can be tweaked only so far before major problems arise and the car reaches its limit.

In many ways, we humans are the fish equivalent of a hot-rod Beetle. Take the body plan of a fish, dress it up to be a mammal, then tweak and twist that mammal until it walks on two legs, talks, thinks, and has superfine control of its fingers—and you have a recipe for problems. We can dress up a fish only so much without paying a price. In a perfectly designed world—one with no history—we would not have to suffer everything from hemorrhoids to cancer.

Nowhere is this history more visible than in the detours, twists, and turns of our arteries, nerves, and veins. Follow some nerves and you’ll find that they make strange loops around other organs, apparently going in one direction only to twist and end up in an unexpected place. The detours are fascinating products of our past that, as we’ll see, often create problems for us—hiccups and hernias, for example. And this is only one way our past comes back to plague us.

Our deep history was spent, at different times, in ancient oceans, small streams, and savannahs, not office buildings, ski slopes, and tennis courts. We were not designed to live past the age of eighty, sit on our keisters for ten hours a day, and eat Hostess Twinkies, nor were we designed to play football. This disconnect between our past and our human present means that our bodies fall apart in certain predictable ways.

Virtually every illness we suffer has some historical component. The examples that follow reflect how different branches of the tree of life inside us—from ancient humans, to amphibians and fish, and finally to microbes—come back to pester us today. Each of these examples show that we were not designed rationally, but are products of a convoluted history.

OUR HUNTER-GATHERER PAST: OBESITY, HEART DISEASE, AND HEMORRHOIDS

During our history as fish we were active predators in ancient oceans and streams. During our more recent past as amphibians, reptiles, and mammals, we were active creatures preying on everything from reptiles to insects. Even more recently, as primates, we were active tree-living animals, feeding on fruits and leaves. Early humans were active hunter-gatherers and, ultimately, agriculturalists. Did you notice a theme here? That common thread is the word “active.”

The bad news is that most of us spend a large portion of our day being anything but active. I am sitting on my behind at this very minute typing this book, and a number of you are doing the same reading it (except for the virtuous among us who are reading it in the gym). Our history from fish to early human in no way prepared us for this new regimen. This collision between present and past has its signature in many of the ailments of modern life.

What are the leading causes of death in humans? Four of the top ten causes—heart disease, diabetes, obesity, and stroke—have some sort of genetic basis and, likely, a historical one. Much of the difficulty is almost certainly due to our having a body built for an active animal but the lifestyle of a spud.

In 1962, the anthropologist James Neel addressed this notion from the perspective of our diet. Formulating what became known as the “thrifty genotype” hypothesis, Neel suggested that our human ancestors were adapted for a boom-bust existence. As hunter-gatherers, early humans would have experienced periods of bounty, when prey was common and hunting successful. These periods of plenty would be punctuated by times of scarcity, when our ancestors had considerably less to eat.

Neel hypothesized that this cycle of feast and famine had a signature in our genes and in our illnesses. Essentially, he proposed that our ancestors’ bodies allowed them to save resources during times of plenty so as to use them during periods of famine. In this context, fat storage becomes very useful. The energy in the food we eat is apportioned so that some supports our activities going on now, and some is stored, for example in fat, to be used later. This apportionment works well in a boom-bust world, but it fails miserably in an environment where rich foods are available 24/7. Obesity and its associated maladies—age-related diabetes, high blood pressure, and heart disease—become the natural state of affairs. The thrifty genotype hypothesis also might explain why we love fatty foods. They are high-value in terms of how much energy they contain, something that would have conferred a distinct advantage in our distant past.