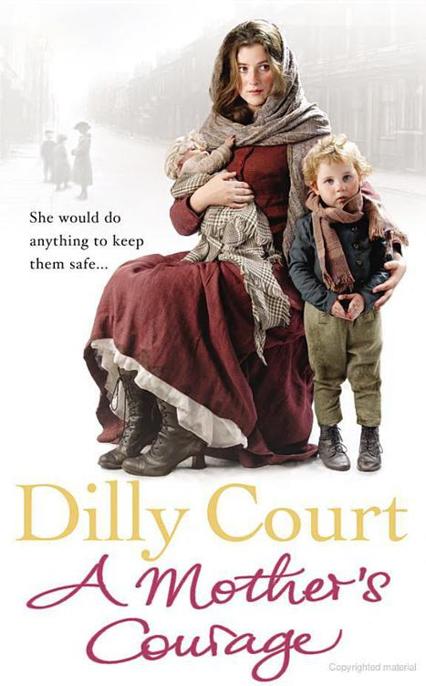

A Mother's Courage

- About the Author

- By the Same Author

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Chapter One

- Chapter Two

- Chapter Three

- Chapter Four

- Chapter Five

- Chapter Six

- Chapter Seven

- Chapter Eight

- Chapter Nine

- Chapter Ten

- Chapter Eleven

- Chapter Twelve

- Chapter Thirteen

- Chapter Fourteen

- Chapter Fifteen

- Chapter Sixteen

- Chapter Seventeen

- Chapter Eighteen

- Chapter Nineteen

- Chapter Twenty

- Chapter Twenty-one

- Chapter Twenty-two

- Also Available in Arrow

A mother's

Courage

Dilly Court grew up in North East London and

began her career in television, writing scripts for

commercials. She is married with two grown-up

children and three grandchildren, and now lives

in Dorset on the beautiful Jurassic Coast with her

husband and a large, yellow Labrador called

Archie. She is also the author of

Mermaids

Singing, The Dollmaker's Daughters, Tilly True, The

Best of Sisters

and

The Cockney Sparrow.

Also by Dilly Court

Mermaids Singing

The Dollmaker's Daughters

Tilly True

The Best of Sisters

The Cockney Sparrow

A Mother's

Courage

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author's and publisher's rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

ISBN 9781407004563

Version 1.0

Published by Arrow Books 2008

6 8 10 9 7

Copyright © Dilly Court 2007

Dilly Court has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and

Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

This novel is a work of fiction. Names and characters are the product

of the author's imagination and any resemblance to actual persons,

living or dead, is entirely coincidental

This electronic book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher's prior consent in any form other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

First published in Great Britain in 2007 by

Century

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London, SW1V 2SA

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited

can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book

is available from the British Library

ISBN: 9781407004563

Version 1.0

For Simon, Marian, Sarah, Julia and Jean in

New Zealand

Although the characters and the events in the

Foundling Hospital are entirely fictional, the

Foundling Hospital did exist. It was founded in

1739 by Captain Thomas Coram as a home and

educational establishment for children abandoned

on the streets of London. Although the

building was demolished in the early 20th

century, the charity, now known as the Coram

Family, still continues its good work in improving

the emotional health and life prospects of

children.

East London, January 1879

A crowd of women had gathered outside the

shipping office in Eastcheap, their pale faces

masked with dread as they huddled together

against the biting east wind. A sleety rain

tumbled from a pewter sky pitter-pattering

softly on the cobblestones, but not a sound could

be heard from those patiently waiting for news

of their loved ones, except for the chattering of

teeth and the occasional muffled sob.

Eloise Cribb stood a little apart from them, but

it was not that as an officer's wife she considered

herself to be a cut above the rest. She was no

snob, and her strict moral upbringing as the

daughter of a clergyman had taught her that all

men were equal, but she was uncomfortably

aware that her elegant mantle trimmed with fur,

and the pert little matching hat, were in sharp

contrast to the shabby clothes worn by wives of

the crew. She had scanned the gathering for the

familiar face of the captain's wife, but she was

not there. Eloise knew that the poor lady was in

an advanced state of pregnancy, and her heart

went out to her. How awful not to know the fate

of your beloved husband when you were about

to give birth to his child. The wives of the second

and third mate were clinging together for

comfort, and, as she hardly knew them, Eloise

had acknowledged them with an attempt at a

smile and then moved away.

She wiped a strand of long dark hair from her

forehead, blinking away the raindrops that

trickled down her face like tears. In her heart she

knew the answer even before the heavy oak door

opened and a whey-faced official representing

the shipping company appeared at the top of the

stone steps. One look at his pinched features

confirmed her worst fears. There was an audible

intake of breath as the wives, sweethearts,

mothers and sisters waited for the inevitable

announcement that the

Hellebore,

which had now

been overdue for several weeks, was lost at sea.

A long drawn out groan of despair was torn from

the women's lips as the official read out the

company's statement in a voice choked with

emotion. Eloise listened but the only words that

registered were those she had dreaded the most.

'The management regrets to inform you that the

tea clipper

Hellebore

went down during a

typhoon in the China Sea with the loss of all

hands.'

A loud animal-like howl of pain was ripped

from a pregnant woman's throat and several

others fainted or collapsed in the arms of their

friends and relatives. Eloise stood quite still,

totally silent, unable even to cry. Her brief

marriage to First Officer Ronald Cribb had not

been perfect, but she had loved him dearly. The

long months of enforced separation had been

hard to bear, but it had made their reunion all the

sweeter when at last he came home on leave. She

shivered convulsively as the harsh fact dawned

on her that her two children, Joseph who would

be three in June and Elizabeth, a babe in arms not

quite four months old, were now fatherless. She

was a widow, and she was virtually penniless.

Stunned and too shocked to feel either grief or

pain, she waited in line while the counting house

clerk handed out the allotments to the distraught

widows. Eloise could tell by his tight-lipped

expression that he was close to tears himself, and

she felt vaguely sorry for him in his onerous task,

but her mind seemed to be detached from her

body as she held out her hand to receive the

small brown envelope. The clerk murmured condolences,

but he could not look her in the eyes

and she saw that his hands shook as he fumbled

for the next pay packet. Eloise moved away from

the head of the queue like an automaton, putting

one foot in front of the other and yet barely

conscious of what she was doing or which way

she was going. All she knew was that she must

get home to her babies: poor fatherless little

mites, who now depended on her for everything.

Blinded by the rain and tasting the salt tears

that were flooding down her cheeks, she

stumbled over the wet cobblestones as she

headed off in the direction of Shoreditch. It was a

long walk to Myrtle Street but she did not want

to waste money on the bus fare, and she needed

time in which to compose herself. Her heart

might be broken into shards, but she must not let

the little ones sense her despair. At least they

were warm and dry at home, safe in the care of

her neighbour's eldest daughter, Mary, who was

a stolid reliable sort of child, and could be trusted

not to leave Joss and Beth unattended.

Eloise headed north towards Bishopsgate,

barely noticing the crowds of workers who were

hurrying homewards. She was soaked to the skin

and her feet were blistered and sore, but she was

oblivious to physical pain or discomfort and she

quickened her pace. She wanted to be at home

with her children. She longed to hold them in her

arms and to inhale their sweet, baby fragrance.

Joss and Beth were her last link with Ronald. Her

breath caught on a sob as the harsh truth dawned

upon her. She would never see him again. She

would never have the chance to kiss him

goodbye, or even have the small comfort of

seeing him laid to rest in a leafy cemetery where

she might lay flowers on his grave. She stumbled

on through the rain-soaked streets ignoring the

curious looks of passers-by, but after a while a

painful stitch in her side forced her to stop and

lean against a shop window gasping for breath.

As the pain ebbed away, Eloise made a concerted

effort to be calm. She must try to think clearly.

She must not panic. As her breathing slowed

down and the fog of misery began to clear from

her brain, she knew what she must do. She

would collect the children and take them home

to the vicarage and to Mother. Mama would

make things right again. She always knew what

to do for the best.

Gaining strength from the thought of her

mother's comforting presence and the familiar

surroundings of her old home, Eloise started off

again, edging her way through the slowly

moving forest of black umbrellas. She tried to

focus her thoughts on happier times, recalling

her first meeting with Ronnie and the heady

days of their whirlwind romance. They had met

at a church social during one of his infrequent

shore leaves. Ronnie was not a religious man but,

having nothing better to do, he had accompanied

one of his shipmates to the social evening, and he

had always teased her about the way they met,

declaring that it was the 'best worst evening of

his life'. Eloise was not fooled by his levity; she

had known the first moment she had set eyes on

him in the church hall that he was the one for her,

and she knew that Ronnie had felt the same. He

had charmed her with his dazzling smile and

craggy good looks. She had noticed particularly

how his bright blue eyes were crinkled at the

corners, caused no doubt by years of gazing

across vast oceans into the far horizon, and his

lively sense of humour had quickly overcome

her initial shyness. They had danced every dance

to the rather out of tune notes of Miss Brompton

on the pianoforte. They had sipped the fruit cup,

which was so well diluted that there was barely

a trace of alcohol in the over-sweet drink, and

they had eaten fairy cakes baked by the Misses

Bragg, two maiden ladies who owned a

millinery in Pear Tree Lane.

'Oy, look where you're going, ducks.' The

strident voice of a costermonger whose barrow

she had bumped against brought Eloise back to

reality with a jerk. She bent down to retrieve the

oranges that had bounced into the gutter, which

was oozing with muddy rainwater mixed with

straw and detritus from the streets. She gave

them back to him with a murmured apology.

He squinted short-sightedly into her face. 'I

should get home and out of them wet duds if I

was you, miss. You'll end up with lung fever if

you're not careful.'

Eloise managed a wobbly smile and went on

her way. Battling against the wind and rain, it

took her over half an hour to reach Myrtle Street.

It was not the most spiritually uplifting of places

in which to live, but the rent was reasonably

cheap, which was essential as they always

seemed to be short of money. Although Ronnie

earned a good wage he was a spendthrift by

nature, and no matter how many times she had

tried to make him live within their means he had

never complied, laughing at her attempts to

balance the housekeeping, and telling her that

'there was plenty more where that came from'.

Cold, wet and tired, Eloise quickened her pace

as she walked down the narrow street lined with

red-brick terraced houses which had been built

half a century ago to house the navigators,

mostly Irish immigrants, who were needed to

construct the vast network of railways. They had

long since moved on, following the progress of

the railways and canals. Now these two up and

two down dwellings were crowded with people

of all nationalities, sometimes two or three

different families sharing one house and a single

privy in the back yard. Eloise knew she ought to

be thankful to have the house to herself, but

living in this deprived area had been a shock

after the relative comfort of the large vicarage in

Dorset where she had grown up. Papa had not

been happy when he was given a parish in

Clerkenwell, but he had seen it to be his duty and

had moved his family from the country to

London. Eloise had been just sixteen then, fresh

from Miss Mason's Academy for Young Ladies,

and hoping that she might go on to become a

teacher, but Papa had insisted that she should

stay at home and assist her mother with her

parish duties. It had not occurred to her to flout

his wishes, and it was no hardship as Eloise

adored her gentle mother; they were the best of

friends, more like sisters, so other people had

often remarked, than mother and daughter.

As Eloise opened the front door, she had one

thought uppermost in her mind. She would put

the children in the perambulator that Ronnie had

bought when Joss was born, and she would take

them home to Mother. She stepped into the front

room and shivered as the warmth enveloped her.

A coal fire was burning brightly in the grate and

beside it sat Mary, with Joss dandled on her knee.

She stopped in the middle of the nursery rhyme

she had been reciting to him and stared at Eloise

with large brown eyes that were too knowing for

her tender years. 'Is it bad news then, missis?'

Eloise took off her sodden, and probably

ruined, fur hat. Rainwater was dripping from her

clothes staining the floorboards on which she

had expended much time and energy, polishing

them until they gleamed like satin. She nodded,

momentarily unable to speak. Joss was holding

his arms out to her, smiling with delight. 'Mama,

Mama.'

She bent down to kiss his curly blond head. 'In

a moment, darling. Mama needs to change out of

her wet clothes.'

'He's not coming home then?' Mary said in a

matter-of-fact voice.

The harsh reality of Mary's words struck Eloise

like a blow, but she bit back a sharp retort. The

child was merely stating the truth. There were

many seafarers' families who lived in the area,

and there were few who had not been touched by

some sort of disaster be it death by drowning or

crippling accidents. She shook her head. 'No,

Mary. I fear not.'

'You go upstairs and change out of them wet

things then, or you'll be next. I don't mind

staying on for a bit with young Joss, and the baby

is still asleep.'

Eloise made her way slowly up the narrow

staircase; the boards creaked beneath her feet

and her high button boots squelched, leaving

little pools of water on the bare treads. In the

bedroom at the front of the house, Beth lay

sleeping in her cradle, her thick golden eyelashes

forming crescents on her rosy cheeks. Her

breathing was so soft that Eloise had to resist the

temptation to touch her, just to make sure she

was still alive, but then the baby stirred slightly

in her sleep and Eloise began to breathe again,

but her relief was tinged with bitterness. It was

so unfair that Ronnie would never see his

beautiful daughter and that Beth would grow up

without knowing her father. Eloise bit back a

sob, and she was trembling as she stripped off

her wet clothes and towelled her skin until it

glowed pink. Her breasts were engorged with

milk and tingling. Soon it would be time to feed

Beth, and she must do this before she could even

think of leaving the house. She must focus on

practical things; it was the only way to keep

going.

She put on a clean shift and her only other pair

of stays, lacing them as best she could with

fingers that burned painfully now that the

feeling was returning to her extremities. She took

a clean white cotton blouse from the cupboard

and a plain navy-blue serge skirt. She took off

her wet stockings and dried the inside of her

boots as best she could with the end of the towel.

She would have to put them on again as her old

boots had worn out months ago, and although

her mama would gladly have bought her a new

pair it was more than just pride that prevented

Eloise from asking for help. Papa was not exactly

mean, but he kept a tight hold on the purse

strings, and Eloise knew that when Mama gave

her money or bought her clothes it came out of

her own allowance, which was not overgenerous.

She sighed as she pulled on a dry pair of much-darned

stockings. Money had been tight since

Ronnie's last leave. He had come home hell bent

on enjoying himself and had taken her to the

music halls, theatres, Cremorne Gardens and the

Zoological Gardens. They had eaten out almost

every night, either taking Joss with them or

leaving him with Mary's mother, Fanny, who

was pleased to oblige for a mere penny or

twopence. No matter how much Eloise had

protested that they could not afford such a

lifestyle, Ronnie had merely laughed. If she

closed her eyes she could still see the merry

gleam in his blue eyes and hear the infectious

sound of his laughter. 'If I can't take my lovely

wife out and show her off when I come home on

leave, then it ain't worth the pain and trouble of

separation.' She could hear him now. 'Don't

worry, my love. I'll send more funds when I get

to my next port of call. I promise you that.' But

like the rest of his promises, that one was never

kept.