A Singular Woman (13 page)

Whatever turmoil there had been, Madelyn and Stanley made their peace with Ann's choices, and they embraced new parental and grandparental roles. “All I know is from at least the day Barack was born, there was total acceptance,” Charles Payne said. “He was their baby, and they loved him from day one.” Stanley, having seen little of his own father after the age of eight, cannot have forgotten how it felt to be fatherless. He must have also remembered the haven he and his brother had found in their grandparents' multigenerational home. Madelyn, having been pregnant herself at nineteen, may have found it easier than some mothers would have to see her daughter as a new mother at roughly the same age. Madelyn, who was only thirty-eight when her grandson was born, “wasn't particularly grandmotherly, mind you,” Maya Soetoro-Ng told me. So she adopted the name Tutu, an affectionate term used in Hawaii for grandmotherâmore palatable than, say, Granny. Over time, Tutu evolved into Toot. Just as her mother had taken in Madelyn and her infant daughter while Stanley was in the Army, Madelyn and Stanley now took in Ann and her son. And just as Leona Payne had made it possible for Madelyn to work at Boeing, Madelyn and Stanley made it possible for Ann to return to school. Madelyn had no intention of letting Ann's changed circumstances derail her education.

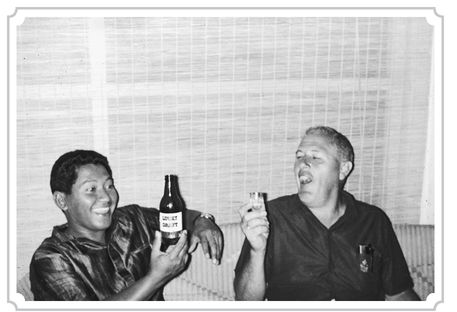

Stanley and Barack

“You have to understand that Ann's mother very much regretted her choices,” Arlene Payne told me. “She would never have let Ann go that way. She had ambitions. She wanted to get on in the world. She realized what a mistake she had made in not going to college. She expressed that to me a number of times, so I think she would never have allowed Ann to not go to college.”

They were opposites in many ways, Madelyn and Ann. In temperament, Ann took after her father, Maya said. They were “people of appetites”ânot content with small portions or small vistas, not willing “to walk in the same circle.” They were gregarious and loquacious. They loved food, words, stories, books, objects, conversation. Madelyn, by contrast, was practical and down to earth. “My mother's favorite color is beige,” Ann would joke to colleagues years later. Madelyn was sensible and unsentimentalânot a “softie,” the term Maya applied to Ann. Maya described her grandmother's dictum as: Buckle down, don't complain, don't air your dirty laundry in public, don't be so restless. “Work hard, care for your family, raise your kids right, and provide for them,” Maya added. “Make sure they have better lives than you. And that's about it.” Madelyn pushed boundaries in her professional life, but she did it by following the rules. “It wasn't that she was doing it differently, necessarily,” Maya said. “She was very much one of the boys in the bank. She wore high heels and women's suits, and she was very ladylike, but she was very aware of bank decorum and the rules of engagement. She just, I think, was incredibly smart and worked really hard. She did whatever was necessary.”

By way of illustration of the differences between her mother and her grandmother, Maya imagined the way they might comport themselves on the same hypothetical path. Ann would pause to pick berries and seeds, study them curiously, find another path, veer off, stop, climb a tree, listen to the bamboo whistling in the wind. Madelyn would start at the beginning, march forward, sure-footed, chest up, head up, until she reached the end.

Did Madelyn counsel Ann to be more prudent? I asked.

“Probably with both of her marriages,” Maya said.

“Mom said that Tutu worried about her and wished that she could take the easier path,” Maya continued. “What was meant by that was obviously that here was someone from a different country, who had different cultural expectations, of a different raceâin a country that had miscegenation laws in place. This was not the easy path, this was not the direct path. I think Tutu, according to Mom, expressed some concern. It was given more in a sigh than a scream. It was just sort of like, âWhat are we going to do?'” She added, “Tutu wished she would be more sensible and get a house and learn to drive and sit still.”

If Ann had a plan, it did not involve sitting still.

She was an unusual figure on campus. Jeanette Chikamoto Takamura was a sophomore when she met Ann during the 1966 academic year. Ann was working part-time as a student secretary in the office of the student government organization; Takamura, active in student government, hung out in the office between classes. Ann struck Takamura as a “natural intellectual,” with an outlook and orientation that was unusually global. She dressed in dashikis, kept African artifacts on her desk, and gravitated in conversation toward international topics. There was something enigmatic about her, Takamura found. She left an impression of detachment, perhaps because she seemed always to be thinking, as though her mind were operating on multiple planes. Takamura met Ann's small, curly-haired son, Barry, whose father, Ann told her, had returned to Africa. The marriage, Ann said simply, had not worked out. On one occasion, Ann stunned Takamura by confiding to her that she wanted to send Barry to Punahou Academy, seen by many as the top prep school in Hawaii. “I'm thinking, âHow in the world is she going to afford this?'” Takamura told me. “I remember thinking, âDo not say anything discouraging.' So I said, âYou know, Ann? I think you'll find a way.'”

Several years earlier, late in 1963 or early 1964, Ann had shown up at “Indonesian Night” at the East-West Center in a borrowed sarong and

kebaya,

the long-sleeved, often cotton or silk blouse worn by Indonesian women. At her side was a twenty-seven-year-old Javanese graduate student named Lolo Soetoro, who had arrived at the university in 1962 in the second wave of Indonesian students on East-West Center grants. Ann and Lolo may have met at the tennis courts on campus; at least, that is how the story goes. “He was quite a tennis player,” Maya said. “She used to comment that she liked the way he looked in his white tennis shorts.” He was good-looking, amiable, easygoing, patient, and funny. He liked sports and he liked a good laugh. Benji Bennington, who was in Lolo's year at the university and went to work at the East-West Center the month he arrived, said, “He wanted to meet people all the time. He wasn't shy about using his English. He had a good sense of humor, and he loved to party. Yeah, he loved to party.”

kebaya,

the long-sleeved, often cotton or silk blouse worn by Indonesian women. At her side was a twenty-seven-year-old Javanese graduate student named Lolo Soetoro, who had arrived at the university in 1962 in the second wave of Indonesian students on East-West Center grants. Ann and Lolo may have met at the tennis courts on campus; at least, that is how the story goes. “He was quite a tennis player,” Maya said. “She used to comment that she liked the way he looked in his white tennis shorts.” He was good-looking, amiable, easygoing, patient, and funny. He liked sports and he liked a good laugh. Benji Bennington, who was in Lolo's year at the university and went to work at the East-West Center the month he arrived, said, “He wanted to meet people all the time. He wasn't shy about using his English. He had a good sense of humor, and he loved to party. Yeah, he loved to party.”

Another Indonesian student, Sylvia Engelen, and a German student she later married, Gerald Krausse, brought a camera to “Indonesian Night” that year. In the fall of 2008, the Krausses opened a well-worn photo album on a coffee table in a living room in Rhode Island, where they had settled. The album was filled with fading snapshots taken in Hawaii and at the university in the early 1960s. There was Sylvia, in a green Balinese costume, and Lolo Soetoro, in a batik shirt and gray trousers. Beside him stood Ann, in her borrowed outfit, her head tilted uncharacteristically and rather demurely downward. “We met her through Lolo,” Sylvia Krausse said, sounding amazed even then by the memory. “When he brought her to âIndonesian Night.'”

With Lolo and Sylvia Engelen, “Indonesian Night” at the East-West Center

Like some Javanese, Lolo had been given one name, Soetoro, at birth. Like the names of his nine siblingsâSoegijo, Soegito, Soemitro, Soewarti, Soewardinah, and so onâhis began with the

soe

-prefix, meaning “good” or “fortunate,” or some combination of both. Born in Bandung in 1936 and raised in Yogyakarta, he was the youngest of the ten. “Everybody loved him, maybe because he was the youngest boy,” one of his nieces, Kismardhani S-Roni, told me. His childhood nickname, Lolo, came from the Javanese word

mlolo,

a verb meaning “to gaze wide-eyed.” All the boys and several of the girls in the family went to college, according to Lolo's nephew, Wisaksono “Sonny” Trisulo. From there, they moved into jobs in fields such as the law, the oil industry, and higher education. Lolo studied geography at Gadjah Mada University, the most respected university in Yogyakarta. He became a lieutenant in the Indonesian army, according to Bill Collier, who knew him at the University of Hawaiâi and later in Indonesia. With the support of the Indonesian government, he became the first member of his family to study outside of the country. In the fall of 1962, he was sent to the University of Hawaiâi on a two-year East-West Center grant to get a master's degree in geography. In return for which, Sonny Trisulo said, Lolo was expected to devote four years to government service on his return.

soe

-prefix, meaning “good” or “fortunate,” or some combination of both. Born in Bandung in 1936 and raised in Yogyakarta, he was the youngest of the ten. “Everybody loved him, maybe because he was the youngest boy,” one of his nieces, Kismardhani S-Roni, told me. His childhood nickname, Lolo, came from the Javanese word

mlolo,

a verb meaning “to gaze wide-eyed.” All the boys and several of the girls in the family went to college, according to Lolo's nephew, Wisaksono “Sonny” Trisulo. From there, they moved into jobs in fields such as the law, the oil industry, and higher education. Lolo studied geography at Gadjah Mada University, the most respected university in Yogyakarta. He became a lieutenant in the Indonesian army, according to Bill Collier, who knew him at the University of Hawaiâi and later in Indonesia. With the support of the Indonesian government, he became the first member of his family to study outside of the country. In the fall of 1962, he was sent to the University of Hawaiâi on a two-year East-West Center grant to get a master's degree in geography. In return for which, Sonny Trisulo said, Lolo was expected to devote four years to government service on his return.

Lolo and Stanley, Hawaii

Lolo was in many ways the opposite of Barack Obama Sr. He lacked Obama's intimidating intensity, his ambitions, the force of his intellect. He was kind and considerate. By temperament, and by culture, he was not inclined to argue. He was calm. All of that was part of his appeal to Ann, whose gale-force encounter with Obama had shaken her up. “It was kind of a reaction to her first husband, who was exciting, but he wasn't exactly a family man,” said Kay Ikranagara, who would become a close friend of Ann's in Jakarta in the 1970s. “Lolo was stable, would work, support the family. She thought that was really appealing.” If Lolo had a tendency to open the newspaper straight to the sports pages and stop there, Ann did not mind that, for a time. He was from a part of the world that was increasingly interesting to her. He was hoping to return to Indonesia, which had emerged from three hundred fifty years of Dutch domination, to teach at the university and become a part of his country's future. “That was part of what had drawn her to Lolo after Barack had left,” the younger Obama would write, “the promise of something new and important, helping her husband rebuild a country in a charged and challenging place beyond her parents' reach.”

Whether Ann was looking forward to a lifetime in Indonesia or simply reaching for an escape hatch is difficult to know.

Intermarriage was not unusual among East-West Center students. Gerald Krausse, who had been working as a busboy in Waikiki, had got tired of food service and enrolled as an undergraduate at the university. “I was mesmerized by all these foreign students,” he told me. “I wanted to be part of it.” He got a job as a grill cook in the East-West Center cafeteria and as a guard in the center's men's dorm, where students would descend from their rooms in pajamas at two a.m. during the Muslim fasting period and start cooking in order to finish eating by dawn. Krausse became interested in Asia. Soon he met Sylvia Engelen, an Indonesian from Manado who had arrived in February 1961 on an East-West Center grant and was studying German and French. When they married in Hawaii in 1966, sixty students turned out for their wedding. There was just one family memberâSylvia's sister, also on an East-West Center grant. The cake, created by Gerald, a trained pastry chef, captured the Hawaii and East-West Center zeitgeist. It was crowned with a globe made of royal icing with two butterflies on top.

From time to time, the East-West Center made an effort to keep track of the marriage patterns of single students on East-West grants.

Impulse,

a magazine published by and for center students, reported in 1975 that students who married after coming to the center had at least a thirty-three percent chance of marrying across national or ethnic lines. “When you put young people in their twenties and thirties together, guess what?” as Sylvia Krausse put it. Were those marriages strong? No, she answered, without hesitation. For years, she and her husband encountered East-West Center alumni at Asian-studies conferences. In some cases, she said, one member of a couple would have had to make his or her career secondary to that of the otherâor give it up. In addition, she said, Asian men who had felt free to be “very flamboyant and open” in the United States returned home to cultural expectations, family obligations, and the influence of parents and relatives. “I think the girls didn't understand, when they went back,” she said. “Especially the American girls.”

Impulse,

a magazine published by and for center students, reported in 1975 that students who married after coming to the center had at least a thirty-three percent chance of marrying across national or ethnic lines. “When you put young people in their twenties and thirties together, guess what?” as Sylvia Krausse put it. Were those marriages strong? No, she answered, without hesitation. For years, she and her husband encountered East-West Center alumni at Asian-studies conferences. In some cases, she said, one member of a couple would have had to make his or her career secondary to that of the otherâor give it up. In addition, she said, Asian men who had felt free to be “very flamboyant and open” in the United States returned home to cultural expectations, family obligations, and the influence of parents and relatives. “I think the girls didn't understand, when they went back,” she said. “Especially the American girls.”

Other books

Better Than Friends by Lane Hayes

Stallo by Stefan Spjut

The Horns of the Buffalo by John Wilcox

Wired by Francine Pascal

Mystery of the Hidden Painting by Gertrude Chandler Warner

Crystal Doors #1 by Moesta, Rebecca, Anderson, Kevin J.

A Company of Swans by Eva Ibbotson

God's Mountain by Luca, Erri De, Michael Moore

Train by Pete Dexter

The Marine Next Door by Julie Miller