A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War (80 page)

Read A World on Fire: Britain's Crucial Role in the American Civil War Online

Authors: Amanda Foreman

Tags: #Europe, #International Relations, #Modern, #General, #United States, #Great Britain, #Public Opinion, #Political Science, #Civil War Period (1850-1877), #19th Century, #History

There was no cathartic pain for Henry Hore. On the night of the fourth, taking advantage of the full moon, he led a burial party to look for Hansard’s body. They found him lying next to the dead rebel. Hore dug a grave and buried Hansard, but he deliberately left the Confederate raider to rot out in the open. “My dear Cousin you must think me quite savage,” he wrote afterward in the bleak surroundings of a dark, filthy barn, “but the carnage of this frightful war and the horrid sights I see every day made me indifferent to human life. At one time I should have never thought of killing anyone, but now can shoot a man without a shake of my hand. I think I am writing to you more as if you were a hard hearted man than a very pretty girl.”

On May 5 the balmy weather was replaced by lashing wind and rain. The Confederate commanders informed Lee that another attack was beyond their men’s strength. The storm provided the Union army with perfect cover as it slowly crawled back over the Rappahannock River. Charles Francis Adams, Jr.’s cavalry regiment was on the other side, part of the skeleton force of mounted troops Hooker had kept behind. He initially discounted the tales from the abject stragglers who stopped to ask for food or shelter, but “in the afternoon came the crusher,” he told his father. They received the order to saddle up and return to their old camp. They found it “deserted, burned up, filthy, and surrounded with dead horses. We tied up our horses and stood dismally round in the pouring rain.”

9

Henry Hore arrived at Fortress Monroe on Hampton Roads a few days later, on May 9, a young man no longer.

10

The magnitude of Hooker’s defeat was numbing: 17,000 casualties to Lee’s 13,000, without gaining the slightest moral or tactical advantage. Lincoln was horror-struck when he read the telegram, exclaiming, “My God, my God, what will the country say?” The press was predictably harsh: “Everybody feels,” wrote Joseph Medill, the editor of the

Chicago Tribune,

and a close friend of the president’s, “that the war is drawing to a disastrous and disgraceful termination.”

11

The

New York World

railed that the “gallant Army of the Potomac” had been “marched to fruitless slaughter” by “an imbecile department and led by an incompetent general.”

12

The country’s frustration with its leaders made the gratitude felt toward the volunteers all the deeper and more profound. A flotilla of boats swarmed the troopship carrying the 9th New York Volunteers as it approached the Battery, at the southern tip of Manhattan. Thousands of well-wishers lined the pier, throwing flowers and waving flags, and a military band escorted the soldiers along Broadway to Union Square. The men were still wearing their filthy uniforms from the siege at Suffolk, but their disheveled appearance seemed to delight the crowds. This was the enthusiastic reception that the seven hundred survivors of the regiment had been imagining for weeks. On May 20, 1863, George Henry Herbert handed over his weapon at the armory, shook hands with his comrades one last time, and walked away. After a disastrous beginning that had made him the butt of the regiment’s jokes, Herbert had grown to love his life in the army. He sailed for England richer by $400, ready to start life afresh.

—

Lee had maintained a sanguine demeanor throughout the battle—until the moment he learned that Stonewall Jackson had been shot. Jackson had been reconnoitering positions when he accidentally galloped into his own picket line. The nervous Confederate guards shot blindly at the group, killing several riders and striking Jackson. Two bullets tore through his left arm; another hit his right wrist. He was also dragged along by his horse and dropped by his stretcher bearers. The damage to his left arm was irreparable; the limb had to be amputated the next morning. Lee sent Jackson a message via the chaplain begging him to recover quickly, adding, “He has lost his left arm, but I have lost my right arm.” As soon as doctors deemed he could be moved, Jackson was loaded onto an ambulance and taken on a twenty-seven-mile journey to a plantation at Guinea Station.

Francis Lawley followed behind, arriving at the plantation on May 7. Jackson had been moved to the estate office, where he could recuperate in private. “With a beating heart I rode up to ask after him,” wrote Lawley. The doctor stepped outside so that he could speak plainly; the general’s wife and infant daughter were inside. Jackson had appeared to be recovering, but late the previous night the classic signs of pneumonia had set in. Lawley knew what this meant: “I gave up all hope of his recovery.”

13

Lawley could not bear to wait for the end, so he boarded one of the trains taking the wounded back to Richmond. On May 8 he sent a letter to the Confederate secretary of war, James Seddon, warning him of Jackson’s desperate condition. Two days later, on the tenth, Jackson died. Lee cried when he learned the news; there was not a man or woman, North or South, who failed to understand the meaning of Jackson’s death or his vital importance to the Confederacy.

20.2

The loss of Jackson posed a dilemma for Lawley. If he made too much of it in his reports, readers might think that the South had suffered a mortal blow. Yet here was an opportunity to create a mythic figure whose heroic end would elevate the entire Southern cause. Lawley did his best, eulogizing Jackson as both an earthly saint and a military genius whose death would only inspire the South to “deeds of more than mortal valor.” (Unfortunately, the blockade was playing havoc with Lawley’s dispatches; his obituary of Jackson reached London before the news of his shooting.)

15

Lawley was so concerned about presenting Jackson’s death in the best possible light that he deliberately obscured the gravity of the situation out west. On May 19, 1863, he finally revealed to the English public that Vicksburg might not be impregnable after all. The news was “contrary to my own and the general anticipation,” Lawley admitted at the end of yet another article on Stonewall Jackson. General Grant had won a series of tactical victories, beginning with a successful night raid by the Union navy on April 16 that enabled the fleet to steam up the Mississippi River past Vicksburg’s thirty-one guns. Grant stopped all the useless digging and canal building and set his army loose against the Confederates. On May 1 his troops crushed the small force holding the town of Port Gibson, thirty miles south of Vicksburg. Suddenly it was as though the wind was at their backs. The Federal army raced toward Vicksburg, fighting four battles in seventeen days, swatting aside the Confederates’ resistance. General Sherman razed most of Jackson, the capital of Mississippi, on May 14, in a fiery portent of what was to come in 1864.

Grant’s success frightened Richmond, but there was no agreement on how he should be stopped. Longstreet thought they should provoke a battle against the Union Army of the Cumberland, which was stationed in Tennessee. This, he argued, would force Grant to divide his forces between the two theaters. Jefferson Davis wanted to send reinforcements to the two Confederate generals defending Mississippi, John Pemberton and Joseph E. Johnston (now fully recovered from his bullet wound). But Lee had his own plan, one so bold and risky that its very audaciousness made any other suggestion appear timid and lackluster. He proposed to lead his army north again—for an invasion of Pennsylvania. The state was unprotected. Hooker would have to withdraw from Virginia to defend Washington. At the very worst, the North would look vulnerable to its own citizens, and possibly, in the eyes of the international community, incapable of winning the war. The Confederate cabinet debated Lee’s proposal for two days and at last agreed, with only the postmaster general, John Reagan, dissenting. Davis decided that Vicksburg would have to be reinforced with regiments from all parts of the South except Virginia.

—

In May 1863, Frank Vizetelly was on board one of the relief trains carrying troops to Vicksburg. He was going out west, Vizetelly informed his readers, because “the campaign in the valley of the Mississippi will, I believe, decide the duration of the war.”

16

He offered no explanation as to why he had missed the Battle of Chancellorsville. Given the state of his debts and his propensity to fall off the wagon, Vizetelly’s absence and his sudden decision to go to Vicksburg were probably connected. The train juddered slowly across Georgia and Mississippi, the track so worn and buckled in places that it was derailed three times. On the last, Vizetelly was thrown hard against the carriage and suffered a concussion. For an hour or two he thought his arm was broken and was relieved to find it only badly bruised. The engineers managed to keep the train going until they reached Jackson, Mississippi, forty-five miles east of Vicksburg. Sherman’s departure was so recent that the city was still burning. Nothing of any value was intact, certainly nothing that might repair the damaged train. “The Yankees were guilty of every kind of vandalism,” Vizetelly wrote with indignation. “They sacked houses, stole clothing from the negroes, burst open their trunks, and took what little money they had.”

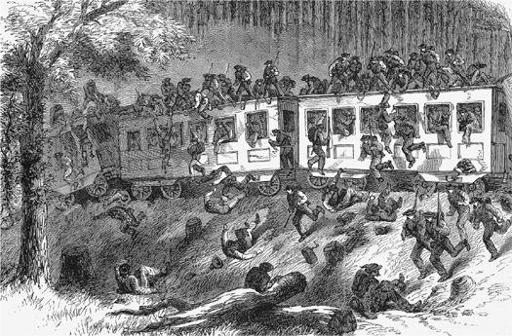

Ill.37

Train with reinforcements for General Johnston running off the tracks in the forests of Mississippi, by Frank Vizetelly.

Now he was not sure where to go. The news from Vicksburg was ominous. The Federal army had surrounded the hilltop town; Confederate general John Pemberton’s army of thirty thousand men was holed up inside, along with three thousand luckless civilians. The Confederate army had enough rations to last sixty days. The fatherless families who cowered in its midst, on the other hand, had only their gardens, their fast-emptying cupboards, and, in the final resort, their pets. Vizetelly decided he had no choice but to stay in and around Jackson. His exploration of the surrounding countryside revealed dozens of dismal encampments, where women and children had clustered together for protection. It was an unexpected sight, he wrote. “Ladies who have been reared in luxury” were living rough like country peasants, “with nothing but a few yards of canvas to protect them from the frequent thunderstorms which burst in terrific magnificence at this season of the year over Mississippi.”

17

Only two months before, Northern newspapers had branded Grant a failure and a drunk. But since then, he had marched 130 miles and won every battle. Charles A. Dana, the observer sent by Lincoln and Stanton to Grant’s headquarters, had seen much that troubled him: the callous, even brutal, attitude toward the sick appalled him, but he never saw Grant incapacitated. In fact, closer acquaintance made Dana appreciate the general’s particular genius for waging war without ever faltering or second-guessing himself. This determined quality stood Grant well once he reached Vicksburg: his first assault on May 19 was a dismal failure. A thousand Federal soldiers fell in the attack, but not a foot was gained. On the second attempt, three days later, he lost another three thousand men. Grant insisted that the army remain where it was. But he also refused to request a flag of truce to allow the wounded to be collected. The injured lay strewn among the dead for two days. The only witness to their suffering was the harsh sun, which putrefied the dead and flayed the living. Finally driven mad by the screams and stench from the ditches, the Confederates sent a message to Grant, begging him “in the name of humanity” to rescue his men.

18

It then dawned on Grant that all he had to do was be patient and starve out the inhabitants. Inside the town, no one believed such a calamity would come to pass. General Pemberton and his men were waiting for General Johnston to lead his army to their rescue. But the cantankerous Johnston had warned Pemberton not to retreat to Vicksburg, and now that it had happened he wrote off the town and the army as lost. Nothing, not even the urgent telegrams from President Davis and Secretary of War Seddon, could make Johnston change his mind and risk his small force of 24,000 men against a Federal army three times the size. His one concession was to send out a request for volunteers to sneak supplies through the Federal lines into Vicksburg. Vizetelly accompanied some of the missions. These forays were exceedingly dangerous. The scouts had to crawl on their hands and knees in the dark for miles, “avoiding every gleam of moonlight, and prepared at any moment to use the revolver or the knife.” Many previous attempts, Vizetelly informed his readers, had ended with the volunteers being either captured or shot. During one particular mission, the intrepid band scrambled along gorges and through pathless woods until they were twelve miles from Vicksburg. There they left Vizetelly and disappeared into a ravine. “As I lay on the ground in the calm, quiet night I could distinctly hear sounds of musketry between the loud booming of mortars,” he wrote. Whether that meant success or failure he could not tell and would not know until the next day.

19