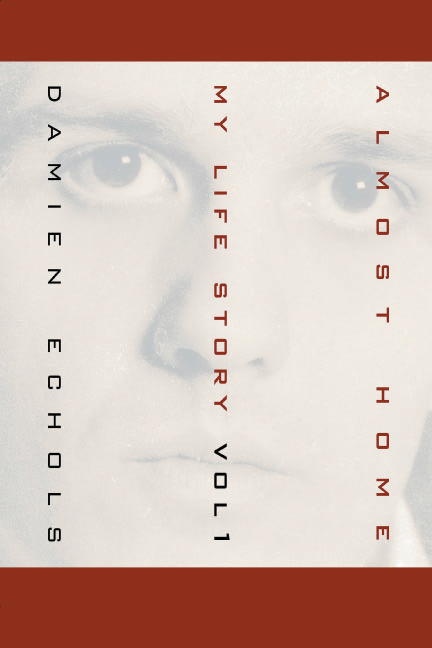

Almost Home

Authors: Damien Echols

Almost Home

Almost Home

✦

My Life Story

Vol 1

Damien Echols

iUniverse, Inc.

New York Lincoln Shanghai

Almost Home

My Life Story

Copyright © 2005 by Damien Echols

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping or by any information storage retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

iUniverse books may be ordered through booksellers or by contacting: iUniverse

2021 Pine Lake Road, Suite 100

Lincoln, NE 68512

www.iuniverse.com

1-800-Authors (1-800-288-4677)

ISBN-13: 978-0-595-35701-7 (pbk)

ISBN-13: 978-0-595-80178-7 (ebk)

ISBN-10: 0-595-35701-6 (pbk)

ISBN-10: 0-595-80178-1 (ebk)

Printed in the United States of America

Contents

iv

Damien Echols

v

Foreword

The first time HBO aired the documentary “Paradise Lost—The Child Murders of Robin Hood Hills,” I was living in the Hollywood Hills, miles and a millen-nium away from stories like these. There is a certain lurid fascination I have always had with crime and criminals, and I had recently found a home in the City of Broken Dreams, where the Manson Family and the Black Dahlia ruled the sickly jaded pop culture of Los Angeles in the early 90s. I had not been prepared for the tragic tale of these boys, who are now referred to as the West Memphis Three.

Filmmakers Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky did an incredibly balanced por-trayal of the trial and conviction of Damien Echols, Jason Baldwin and Jesse Misskelley. The documentary commented neither on the possible innocence or guilt of the three, who were tried as adults for the heinous murders of three younger boys, Christopher Byers, Steven Branch and Michael Moore. Berlinger and Sinofsky did what great documentary filmmakers do, document. They shot, kept shooting, kept eyes on all who were involved in a case that was obviously incredibly doomed from the start.

No evidence linked the West Memphis Three to the murders, besides an admis-sion of guilt by Jesse Misskelley (who possesses an IQ level of 73), forced out of him after twelve consecutive hours of questioning, with only the last forty five minutes put on tape. It was more a fabricated rendition of what the law officers wanted to believe happened that terrible day in Arkansas, than a confession. It was something to appease the local community, locked in a “Satanic Panic” like a scene out of “The Crucible,” a vigilante mob looking for a witch to burn, who wanted justice even if that justice was actually unjust. This pitiful piece of “evidence” was enough to convict all three of capital murder and resulted in life sentences for Jesse and Jason, and death by lethal injection for Damien Echols, scheduled for the year 2000.

I was outraged. Yet, it seemed as if the documentary would have been enough to exonerate these kids. The truth was blatantly there, on the screen, and couldn’t vi

Damien Echols

vii

be denied. I thought the justice system would soon undo its wrongs, because I believed in America then, so much more than I do now. My roommate made me a prayer box, with a photograph of the still adolescent Damien on a string inside.

Later, I found a large paperback that formed a kind of yearbook for all the death row inmates in America awaiting execution. Damien’s photograph and name were in the book, now almost two years after the case had gone to trial. Then, the second documentary “Paradise Lost II: Revelations” aired on HBO. This film focused on the wake of the convictions, the formation of Free the West Memphis Three organization by Burk Sauls, Kathy Bakken and Grove Pashley, the system of appeals the now young men were facing, their reflections on their unjust sentencing and the incredulousness of the different groups of people who identified with the WM3. It seemed that having long black hair, a love of heavy metal music and a tendency toward esoteric reading could get you the death penalty, and the backlash was starting mobilize.

The sequel also carefully studied the idiosyncratic and suspicious behavior of Mark Byers, stepfather of one of the slain boys, whose wife had died mysteriously after the trial, and who was accused later of forcing two young boys to fight each other and abusing another family’s child. Byers is currently serving time in prison for a number of other unrelated offenses. After viewing this film, I still somehow believed that the justice system would correct itself, that the movement to free the innocent was enough and that America would do right by the law. I thought possibly a third documentary would be in pre-production, one that would be about the day the WM3 would walk out of prison, no longer incarcerated by an intolerant and ridiculous court that could let the real killer go free, thinking that convenient scapegoats (who did not have the funds for proper legal representa-tion, let alone costly forensic testing) would be enough to appease not only the community of West Memphis, but justice itself.

The third film is starting production. The Berlinger-Sinofsky team has gone on to make a documentary about Metallica, who generously donated their music to Paradise I & II, and hopefully III, and two feature films are in pre-production about the WM3. The website WM3.org flourishes, and celebrities like Eddie Vedder and Winona Ryder have championed the cause with speeches and consid-erable financial donations. Many articles, essays, compendiums, and books, including the definitive “The Devil’s Knot,” by Mara Leveritt, have been written on this compelling and disgraceful miscarriage of justice, about the discrimina-Damien Echols

viii

tion of those who are “different” in a community where conformity is law and far more restrictive than anything that is on the books.

More than a decade after learning about this travesty, I decided to write to Damien Echols. I made a donation to his defense fund, and bought him some books from his Amazon wish list. He wrote back to thank me, and asked if I was a comedian. I said that I was, and that I had been following the case for many years, and could not understand why he was still on death row.

We became fast friends. I wanted to know how he was doing, how he survived, how he could still retain a sense of humor and continue to develop as a human being in such a desperate climate. He granted me an interview on my website, and we now regularly have dialogues from his cell on death row. His words are read by countless people around the world, typed into my computer, from his tiny, elegant script, always on long, yellow legal pads. It is humbling, for he has never seen the internet.

I realize that I take so much for granted, like life, for instance. Some have not that luxury. I imagine that being on death row is like having a terminal disease, and the race to find a cure is running alongside you, sometimes fast, or slow, depend-ing on whatever else is happening. You gain, you lose. Momentum is both your savior and your nemesis. How does one live with that?

We write to each other on an almost daily basis. It is all merely my questions, and his answers. I wanted to hear more, because his story has been told by so many, but not yet by him. His story is far more than a gross miscarriage of justice, but a tale of uncommon wisdom and redemption, faith and love, forgiveness and a diverse passion for Wagner and hair bands like Kixx and Skid Row.

Damien Echols is a holy man, as well as a complex, hilarious, erudite, brilliant, forthright, seeker of knowledge and truth. He also secretly loves pro-wrestling!

His capacity for understanding and tolerance run deeper than any other “guru how-to” I have ever spent my self help money on. He and his wife, Lorri Davis, have become sort of a surrogate family for me. Their bond is tremendously lov-ing, and they remind me of my husband and myself. We are a mirror image, although their reflection is distorted by injustice and the reversal that in his case, Damien was guilty before being allowed to be proven innocent. If we are the land

Damien Echols

ix

of the free, the West Memphis Three must be released. They are political prisoners, and until they are free, none of us are free.

Damien Echols is the Heavy Metal Dalai Lama, the Nelson Mandela of Rock and Roll, the Deepak Chopra of Death Row. He keeps equanimity and compas-sion in a place where most would have lost their minds and so many have already lost their lives. His spiritual practice is inspiring in its ability to allow him to cope with what would be literally hell for everyone else. He has become my teacher.